What if, suddenly out of the blue, I insisted that you stop trying to control other people?

What if I said that, when you try to control what other people say or what they do, it’s just a symptom of your own insecurity? And what if I said you needed to do some

tough personal work on yourself first, before trying to make other people conform to your expectations of how they should act towards you? And what if I said that, eventually, if you actually did that tough personal work, you’d almost certainly stop trying to control others anyway?

How would that make you feel?

And, most importantly, would it change your behavior at all…?

Or would it just piss you off? Perhaps make you challenge my self-appointed role in policing your behavior? Would you maybe ask:

“Who the heck are YOU to tell me what I can and can’t do???”

Okay then. So now consider the following situations:

- A woman doesn’t like the way a man is touching her arm.

- A transgender person wants coworkers to use their chosen pronoun.

- A gay person is offended by the homophobic jokes of fellow students.

- A Vegan is horrified when someone brings a meat dish to a potluck at their home.

- A person of color feels alienated by a politician using coded language – language that reveals prejudice or even hatred towards their race.

- A religious person feels persecuted and excluded by a law, a business practice or a cultural tradition that belittles or contradicts their beliefs.

- A person of a particular political persuasion believes another group routinely looks down on them, dismisses their ideas, and laughs at their beliefs.

- A member of one socioeconomic class feels targeted and oppressed by members of other socioeconomic classes.

- A politically correct audience is angry and judgmental about a comedian’s sense of humor

regarding any-of-the-above.

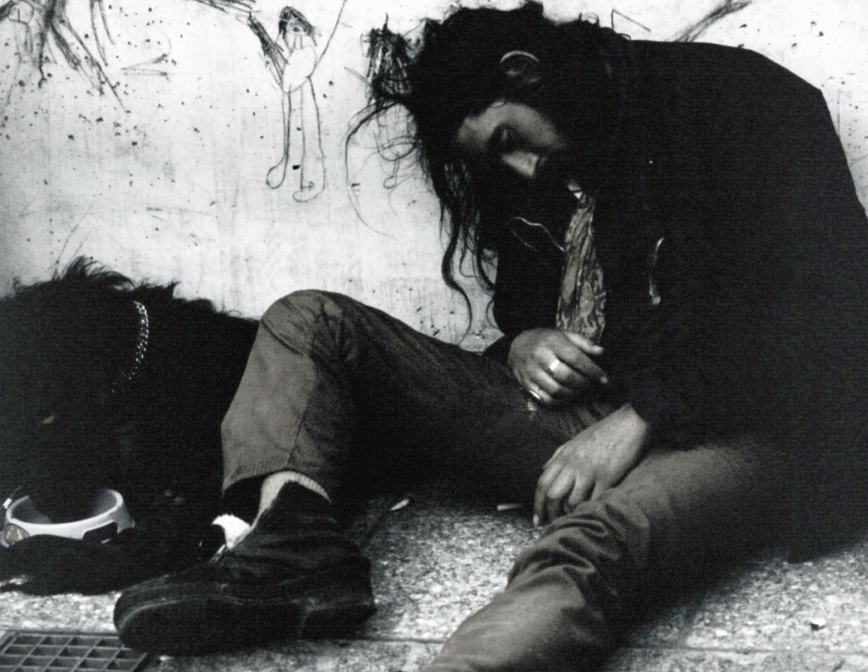

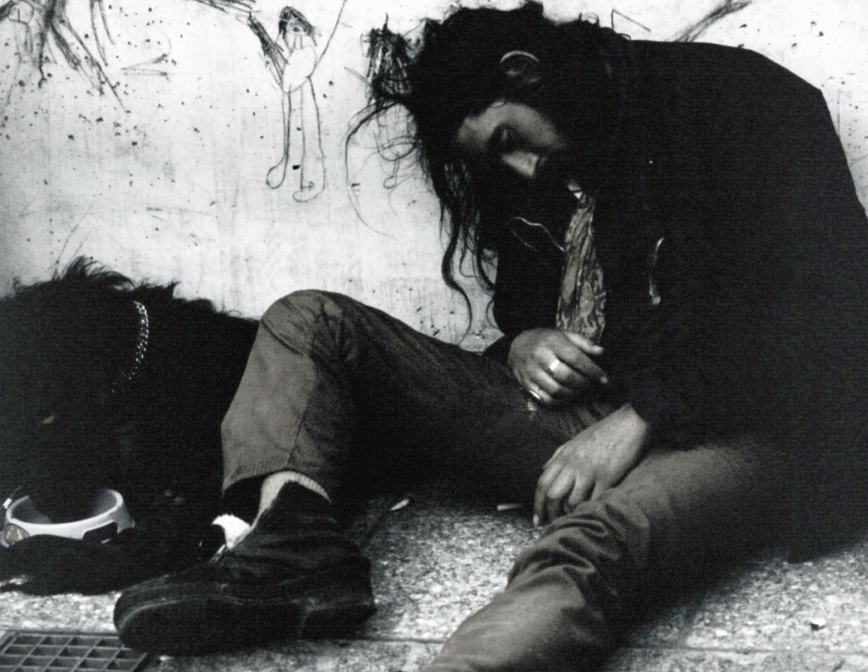

These examples aren’t meant to be equivalant, but in any of these situations there can be real emotional pain involved –

a genuine felt experience of demeaning oppression – that could lead to debilitating despair over time. But, even though real harm may be occurring, does the offended person have the right to demand that those causing offense be ridiculed, shamed, accused or blamed? To demand that they apologize, admit they were wrong, and commit to changing their behavior? To insist they be punished in some way – that they resign, be fired, lose status, be publicly harassed, or are deserving of threats and intimidation? To essentially become an example of accountability for all similar wrongs experienced in society...

a scapegoat for those collective ills?

Can you see what is really happening here?

It isn’t just that the abused is turning into an abuser – it can be much subtler and more insidious than that. For if each of these individuals (or groups of folks) insists that everyone else conform to their particular standard of conduct, to respect their particular sensitivities, to always consider their feelings and perspective and honor their particular belief system…well,

then this leads to everyone constantly policing everyone else’s behavior, and thereby amplifies mistrust and even hatred. And this, in turn, has everyone pissing everyone else off, to the point where we all declare:

“Hey, what gives YOU the right to tell me what I’m allowed to say or do?!” And so we all begin to resent the shackles that our society seems to be placing on us; we all begin to question whether living in harmony with each other is really worth it – and whether our civic institutions are all that important…or worth preserving. We begin to doubt the very foundations of civil society itself.

And yet there is increasingly a reliance on impersonal institutions, the court of public opinion in mass media, and often disproportionate personal punishments to correct what are essentially ongoing cultural and interpersonal challenges. Whether it is a left-leaning social justice warrior or right-leaning religious conservative, promoting the imposition of personal preferences via such impersonal mechanisms is actually destroying the social cohesion required to repair these longstanding problems.

And this is where we have arrived in the U.S. culture of 2019. In every corner of our current political, religious, racial, and economic landscape, folks are arming themselves with accusations against other people who don’t seem to respect or honor a particular boundary or standard of behavior.

Everyone is able to take offense, and demand that everyone else change. And then the most impersonal, coercive and punitive of institutional tools are used to seek remedy. It is as if we have arrived in George Orwell’s

1984 – or even Golding’s

Lord of the Flies – or the worst periods of the Soviet era, or Nazi Germany, or the darkest days of McCarthyism, or the ugly history of the Inquisition…times when folks were ratting each other out to gain praise from those in power, or achieve brief political advantage over someone else, or garner a little more social capital in circumstances where they felt disempowered, or were simply taking revenge on people they didn’t like – and then taking pleasure in their suffering. And, as a consequence, in every one of these historical situations, civil society itself was eventually degraded by pervasive mistrust and mutual oppression.

Is that what we want? Do we want to head any further down this dark and dismal path?

If not, then we need to rethink what is becoming a reflexive and widespread culture of blaming, accusing, ridiculing, shaming, and punishing.

For at its core, when we ask other people to change their behavior to make us feel more comfortable or safe,

we are actually giving away our power. We are offering them all the agency in a given situation, and abdicating our own. We are reinforcing our victim status, and strengthening the bullies even as we attempt to punish them. Often, we may even be galvanizing opposing tribes against any hope of reconciliation. We are, in effect, perpetuating both conflict and our own disempowerment at the same time, rather than solving the underlying problems. And as we give away our own power – while at the same time challenging and undermining everyone else’s – we end up destroying the voluntary trust, empathy and compassion that bind society together. Instead, we replace it with fear.

So…what is the alternative?

There are many observable options that have proven more effective, so why not return to those? For example, in each of the awkward and uncomfortable situations described above:

1.

We can fortify our own emotional constitution, instead of taking offense. We can become stronger and

more secure in who we are, without expecting others to respect or honor us. This may require some real interior work on our part – some genuine fortification of spirit, mind and heart – but the result will be that we won’t constantly require others to conform to our expectations anymore.

2.

We can calmly ask for what we want – not as a self-righteous demand, but as a favor from someone who says that they want to have a professional or personal relationship with us. If they really care about us, perhaps they will at least try. But if our response is met with scorn, dismissiveness or skepticism, we have the option of letting it go. After all, that person’s approval, acceptance and conformance is not required…because we have become more confident and secure in ourselves. We don’t need to demand their conformance –

and why would we want it, if it doesn’t come from a place of respect, understanding and compassion?

3.

We can accept where other people are, let go of judgement, and be a positive example for them. This is what authentic, effective leaders (and parents, and managers) do:

they lead by steadfast and dedicated example…not through blaming, threats, accusations or fear of punishment. Bullying is the easy way out. We can do better.

4.

We can passively, actively and nonviolently resist. We can refuse to participate in activities, systems, environments and relationships that demean who we are and what we believe. We can then vote to support compassionate candidates and friendly initiatives. We can purchase goods and services from those who are supportive to our identity and beliefs. And we can do this without hatred, without fear and anxiety, without shame or blame.

5.

We can create supportive communities, while also cultivating challenging relationships that bridge differences. We can surround ourselves with like-minded folks who nurture and encourage who we are and what we believe – especially in our closest relationships. At the same time, we can also cultivate friendships and social or professional connections with people who are different, who disagree, who aren’t as accepting or as tolerant. For how else can we teach by example, or demonstrate compassion, empathy, tolerance and acceptance if we don’t have such diverse relationships in our lives?

6.

We can be brave…and bravely be ourselves. We can speak our truth, share our perspectives, broadcast our preferences, celebrate our identity, and proudly honor our chosen tribe…without making others feel belittled, excluded, accused, blamed or shamed. We can joyfully be who we are, while also being welcoming and kind at the same time. We can be stalwart in our own principles, while being generous towards those who do not share them.

This is what real power and agency looks like.

7.

We can recover our sense of humor. Perhaps it’s time to allow just a little bit of playfulness back into our lives and public discourse. A little bit of good-natured joshing. Humor isn’t by definition “mean-spirited.” There is a difference between a joke and a slight – and often this is has

just as much to do with how the humor is received, as with how it is intended. If we are always reactive, always defensive, always on-edge…well, we are not likely to be able to create or maintain the relationships required to heal a polarized society. Perhaps, if we let a little humor back into our world, we wouldn’t all be so angry, defensive and fearful so much of the time.

These are the methods that make a real difference over time, that can effectively heal through compassionate and welcoming personal relationships, rather than deepening divides with institutional vindictiveness and “Us vs. Them” groupthink.

In essence, if we want everyone in a diverse and multifaceted society to thrive together, then we all must assert our own place and space to do that –

not by demanding others create that space for us, but by claiming it ourselves and standing firm…without anger or condemnation towards anyone else. In essence, we need to stop blaming and accusing. This is not easy, but it demonstrates genuine strength of character. And it is the content of our character by which we all would prefer to be judged, isn’t it? I think we need to return to this standard of measure, if we want to avoid spiraling backwards and downwards, into the greatest horrors of human history.

Just my 2 cents.