Thanks for the question. “Brief” isn’t going to cut it. Despite popular myths and misconceptions, you can’t impart real wisdom, history or quality information in a tweet…and even clever parables have their limitations. So discussing socialism in any meaningful way will take some time. The age of the child, and how much they already know about the world, will also require different approaches. But here’s one simplified version you could try:

First gather together a hammer, some of the child’s favorite toys, a pile of clothing, and a bag of unbuttered popcorn.

1) A long time ago, before your parents were even born, there were no factories. People often made things themselves at home (like this clothing, for example, or these toys, or this popcorn). Or, if they had enough money or a skill of equal value to trade with someone, they could have other people make these things for them. Other folks actually had servants or slaves to make things for them.

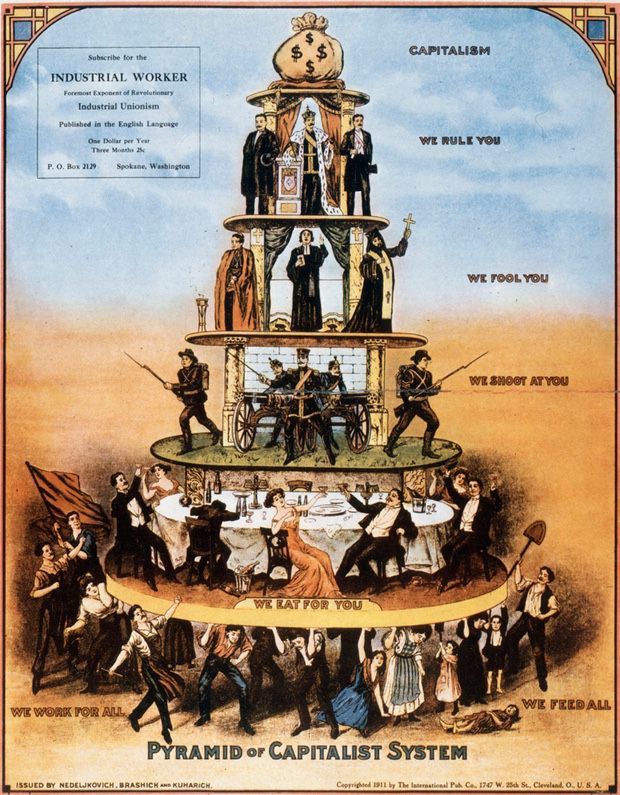

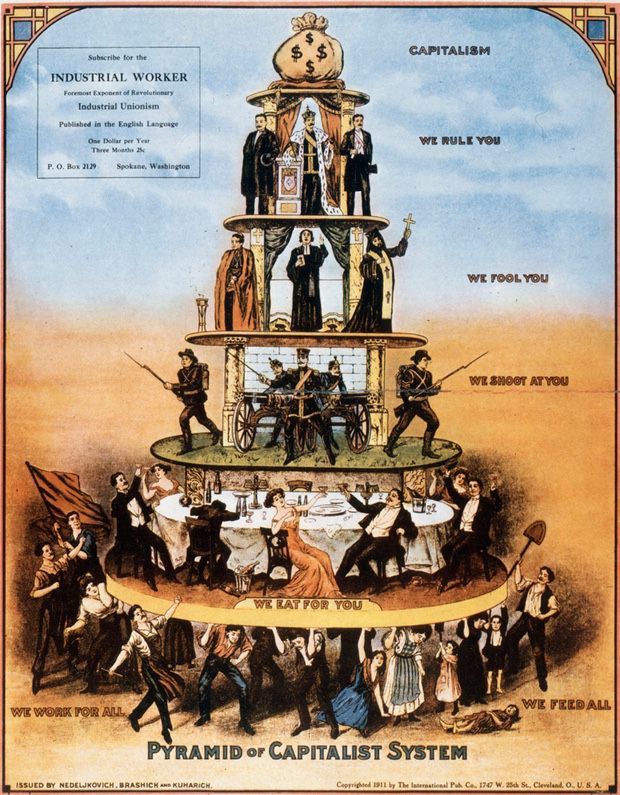

But at that time, not everyone could have everything they wanted! Imagine that. Some people could have lots of toys and clothes and popcorn…but most people could only have very little. And some people — the very poor and the slaves — might not have any at all. As a result, there were some very rich folks who had all of the money and freedom, and who controlled most of society — but all of the poor people (

which was most of the people!) had very little say in things.

2) Then the “capitalist” factories arrived. How this happened is another story in itself…but it changed

everything. Suddenly people didn’t make things at home anymore, or rely on a few skilled people to make them, or have slaves do the work. Instead, huge buildings full of workers made things…and made LOTS of them. Imagine a steady supply of toys, clothing and popcorn now available for

everyone. And one very promising hope was that the workers in the factories got paid money so they could (in theory, at least) buy some of the things they made! The basic idea here was that, because of factories, more and more people could have more and more stuff. Now, even the very poor people could get a job at a factory with the hope of buying some toys and clothes and popcorn!

3) This seems like a pretty good deal, right? But then people started noticing some not-so-good things about these factories — and the cities that grew around them. For example, the factories would hire anyone — including little kids not much older than you —

and work them really hard. Children, mothers and fathers all had really long work-days, too…sometimes ten hours or more…and without any breaks! Often the factories would keep people working all week long. No days off! And the working conditions were also often horrible and unsafe. Workers would get injured, or sick, from their jobs in the factories. Sometimes they even died or were maimed for life because conditions were so bad. And the worst thing was,

the folks who ran the factories didn’t do anything to help the workers who were injured or sick — they would just hire new ones to replace them instead. In addition to this,

the wages paid to work at the factories were very low. So low, in fact, that many factory workers often couldn’t even afford the things the factory made. And, lastly, the cities around these factories were becoming unbearably toxic with pollution from the factories. The air became unbreathable, lakes and streams became so polluted that all of the fish died and no one could drink the water, and even the soil itself became so spoiled that nothing would grow in it.

4) So where did the promise of spreading prosperity go…? Who was getting rich while everyone else was getting sicker and poorer, and the land, water and air was becoming poisoned? And who was actually buying what the factories made?

It was the “capitalist” owners and managers of factories who were getting rich, and who could always afford to buy factory-made goods, and make the time to enjoy them if they wanted to. Isn’t that interesting? So it ended up that the factory workers, who were risking their health and lives, gave up most of their time and well-being to make things for the factory owners and managers, who were enjoying most of the fruits of the workers’ labor. And those owners and managers got richer and richer, and bought more and more toys and clothes and popcorn, and had more and more time to enjoy life…while the factory workers just kept…well,

slaving away at their jobs. So this would be like me keeping all of your clothes, your toys, and this popcorn for myself…and not letting you have any, even though you yourself made the clothes, toys and popcorn!

Do you think that is very nice?

5)

Well, “socialists” didn’t think that this situation was very nice. “Socialists” believed that everyone should benefit from the goods the factories made. These socialists also thought the factory owners had too much power, were being too greedy, and weren’t treating workers in a kind or humane way. So socialist movements tried to protect workers from harm, give them better wages, and offer them a better life

that was less like a slave’s. Many socialists thought the best way to do this was to have governments — which would be elected by a majority of workers — oversee how the factories were run. Some socialists thought that factories should be taken away from their original owners altogether! Other socialists believed that the government shouldn’t be involved at all, but instead that small cooperatives of people should control how things were made and distributed in their community…and between their community and other communities.

But the idea was that, if the public — all of society — had a say in how toys and clothes and popcorn were produced and distributed, then there wouldn’t be so many poor people, or terrible working conditions, and a lot more folks could enjoy these things together. Wouldn’t you like some popcorn? Well, lots of people agreed with this, but the question for socialists then became:

how could society bring this new arrangement into being?

6) Now two of these socialists were named Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and they came up with a version of socialism called “Marxism.” Marx believed that, in order to make the capitalist factory owners kinder and more fair,

there had to be a revolution led by the workers. That is, he thought the only way to make socialism happen was through a big fight, where the working class rose up against the factory owners, and took the factories away from them by force. Eventually, Marx thought, this revolution would lead to an end result — many years in the future — where all people would live in more harmony with each other, and their wouldn’t be differences in class, or wealth, or political power, and everyone would be involved in making decisions together (including about how clothing was made, how toys and popcorn were shared, and so forth).

This eventual conclusion of the revolution would be called “communism,” and Marx famously described the communist ideal this way: “From each according to their ability, to each according to their need.” So folks in a communist society would make toys and clothes and popcorn together, according to their ability, and then give those toys and clothes and popcorn to the folks who needed them.

7) Unfortunately, there was a

big problem, and that was that many of the people who tried to carry out Marx’s violent revolution (and much of this happened after Marx passed away) didn’t really follow through on the rest of his ideas. Instead of giving the power and authority in society to the workers, as other socialists (and Marx himself) had planned to do,

they kept the power for themselves. They did take the factories away from the rich owners, along with all the rich folks’ money, and used the workers to fight this violent and bloody takeover…again, using workers kind of like slave soldiers. But then the rulers of the revolution kept all of the money and power for themselves — and they ended up with all the best popcorn, all the best toys, and all the best clothes. So the basic situation — suffering workers slaving away for wealthy leaders who had all the control — really didn’t change. So the “revolution” never led to the “communist” ideal that Marx and Engels envisioned…

even though it was still called “Communism” by many people!

Now in other places around the world, “socialism” was put into practice without a violent revolution. This is where our worker’s labor unions came from, and worker’s rights and protections at factories — so they could be safe and work a reasonable number of hours in a day, a reasonable number of days in a week, had time off for recreation, and so on.

Socialists are why we have weekends and vacations! You’ve probably also noticed that children like you aren’t working in very many factories anymore either, and that was because socialists advocated for laws making child labor illegal. And there are now also certain factories and services that are run by the government as well, so that everyone can have equal access to their products and service. This is called “socializing” something. So socialized medicine, socialized transportation, socialized retirement, and so forth…these are all a result of socialism, and help all of society have more freedom and feel safe, with everyone sharing the costs and benefits together. There are also companies that have “socialized” themselves — that is, given ownership of the factory to the workers, so the workers manage themselves. But the key to all of this…

and this is important…is that these “socialized” societies always have open and fair elections — they have a strong democracy, where everyone can vote. Because if the workers can’t vote, well then there won’t really be freedom and equality, will there? What if, whenever you asked for popcorn, or new clothes, or a new toy, I always said “No, you can’t have that?” That’s what a dictator or authoritarian does. In this way, socialism is really part of almost every capitalist, democratic country in the world today, and socialist ideas are used whenever their needs to be more freedom and equality in a society…

as long as there is also democracy.

9) Finally, you have probably been wondering what this hammer is for, right?

This hammer is the threat of fascism and totalitarianism. I won’t go into what causes people to become fascists and totalitarians…that is a story for another time, but let’s just say it is a kind of mental illness that spreads through a mob. Fascists and totalitarians have no respect for equality, freedom or fairness…no respect for anyone but themselves, really. All they are really good at is destroying democracy and civil society —

that is, taking away people’s freedoms and equality. Imagine if I smashed all of your toys with this hammer! That wouldn’t be very nice, would it? But that is what fascists will do if you don’t give them whatever they want. They are big bullies. And that is why, when you are old enough to vote, you want to be very careful about who you vote for. Now, after we have put these clothes away, maybe you and I can have some popcorn together, and play with your toys. What do you think…?

My 2 cents.