We live in a world where lies run rampant, where public figures consistently misrepresent the truth, and where once trusted news sources are no longer viewed as reliable. More than ever before, it is now our individual responsibility to discern what is true and what is not, and to recognize when we become the target of deliberate hoodwinking. It is no exaggeration to claim that the durability of our political systems, the stability of our society, and the health of our planet increasingly depend on our vigilance in this arena. What follows is a brief but detailed overview of how to identify bad information, how we can protect ourselves from it, and how we can best respond to its increasingly loud and invasive presence in our lives.

First, what constitutes “bad information?”

Here are some of the hallmarks that help us quickly and reliably identify misinformation, disinformation, propaganda, and manipulative deception:

1.

Partial truths that rush to a sweeping conclusion. One of the most common techniques of communicating bad information is to offer only a small portion of cherry-picked facts for a given situation, deliberately omitting additional information that could provide a more balanced or measured perspective, and then quickly rushing into what is usually an extreme and unreasonable conclusion fueled solely on that partial information.

2.

Fear or hate mongering – often involving conspiracy thinking and demonizing particular individuals or groups – followed by urgent and imperative calls to action. Negative emotion can be profoundly persuasive, even when the accusations being made have no evidence to support them. And once we have been caught up in strong feelings of foreboding or dislike, our rational faculties tend to shut down, and we may make decisions or take action based on strong emotions alone. And propagators of bad information know this, deliberately using it to their advantage to persuade us to conclude or do things we normally wouldn’t.

3.

Visceral and vehement rejection of any reliable sources of information. Those who perpetuate bad information cannot tolerate or allow sources of more accurate information to be consulted by anyone, so they will attack them endlessly – though here again often without evidence to support their accusations.

4.

The illusory truth effect. The illusory truth effect is when everyone begins to believe falsehoods are true simply because they get repeated by lots of people – because we are hearing them from multiple sources, the untruths begins to feel familiar and acceptable. Mainly as a consequence of the Internet, enduring falsehoods can now be spread very quickly all around the globe and become accepted into the mainstream as widely believed “truth” in this way.

5.

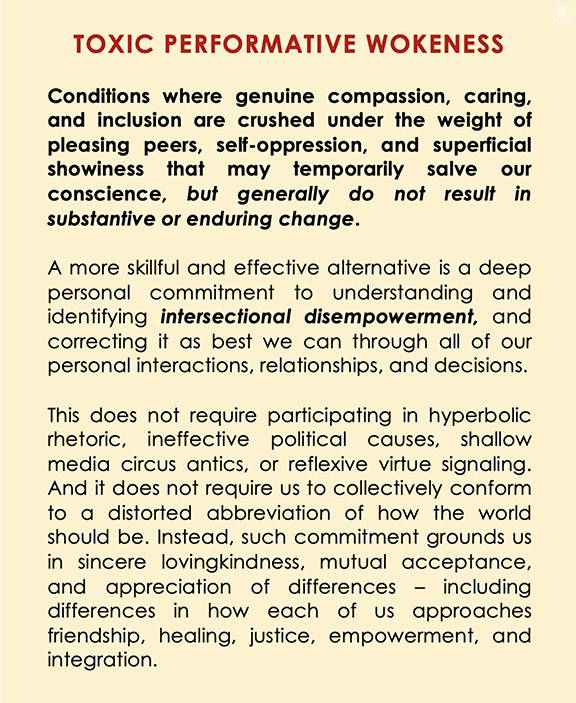

Tribal conformance and groupthink. This technique relies on peer pressure and perceived threats to identity and belonging within a given group to generate lockstep conformance – often within a rigid set of values, priorities, and beliefs. Members of that tribe must, of necessity, conform to a given conclusion or course of action, and endlessly parrot particular talking points, to avoid being kicked out of their tribe. As inherently social creatures who crave acceptance and belonging, these are powerful pressures to keep us in line and make us feel we must propagate bad information…or else.

6.

Reliance on a cult of personality or an idealized self-image. In an age of media celebrities who boisterously portray themselves as champions and heroes without any real evidence or history of their actually being that, adoring followers are lured into accepting falsehoods without question and then vehemently defending those falsehoods. They are, after all, defending a champion and hero that has inspired their adoration and made them feel important and “part of something,” perhaps even making them feel better about themselves and closer to an idealized version of who they want to be.

7.

Projection, false equivalence, and whataboutism. These techniques attempt to paint the opposition with the flaws, faults, mistakes, and failings of the person trying to defend themselves or make their case. For example, someone who is profoundly corrupt or immoral asserting that their opponent is actually the one who is corrupt or immoral; this is projection. Or a politician claiming that an opposing party’s policies or practices have been just as flawed and destructive as their own, when this is only partially true; this is false equivalence. And, finally, when cornered with undeniable evidence of their own misdoings or malfeasance, someone may counter that their accusers have done something similar, when once again this may be only partially true or even false; this is whataboutism.

8.

The constant promotion of other logical fallacies – such as ad hominem attacks, straw man arguments, the bandwagon effect, slippery slope fallacies, appeals to authority, appeals to emotion, false dilemmas, appeals to ignorance, false cause, manufacturing a “big lie,” and many others. Getting to know what these logical fallacies look and sound like can be very eye-opening – but they do take a bit of time and effort to fully appreciate (see

References and Resources section below for more). In brief:

ad hominem is simply attacking the character of a person rather than responding to their actual arguments;

straw man is misrepresenting the opposing viewpoint so that refuting it doesn’t address the actual argument;

bandwagon is claiming that because “everyone already knows” something to be true, is common knowledge, or will succeed, then it must be so;

slippery slope is claiming that even a small admission, concession, or seemingly insignificant course of action will inevitably lead to much broader and disastrous results;

appeal to authority asserts that because a trusted person or source claims something is true, it must be true;

appeal to emotion is just that – there is no rational reasoning or factual evidence involved;

false dilemma is insisting the only available choices are between two black-and-white extremes, when in reality there are more nuanced alternatives;

appeal to ignorance takes advantage of our not having contrary, factual information to contradict the appeal;

false cause links an incorrect cause to a given outcome; a

“big lie” is a distortion of factual reality that is so grandiose and extreme – and repeated so often – that uncritical hearers begin to believe it.

9.

The appearance of reasonableness. This is, for me at least, one of the more insidious techniques used in bad information. The objective here is to make an argument – usually one based on partial information, logical fallacies, or distortions of fact – in a reasonable, logical, and confident way that makes a given opponent or their viewpoint seem extreme, irrational, or hyperbolic. This technique is often combined with other methods meant to provoke the opposition into emotional reactions or overstatement of their position, and thereby undermining the credibility of their viewpoint.

How can we best respond to and mitigate these influences?

As you can see,

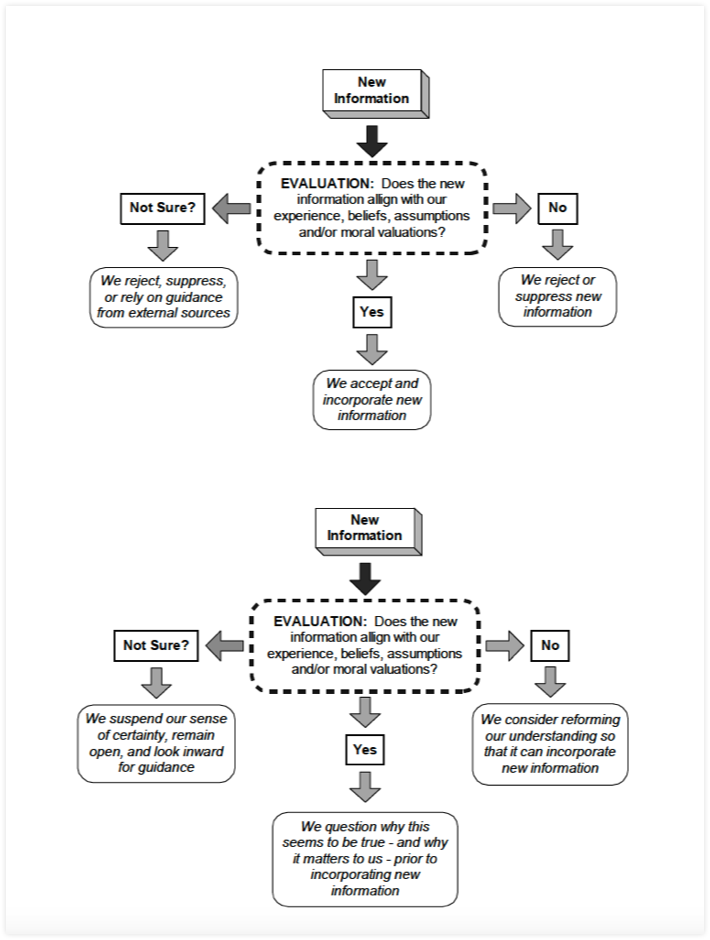

there are a lot of tools in the bad information toolkit. And, unfortunately, once we become conditioned to respond to these tools, it is very difficult to free ourselves from their influence and not react impulsively or reflexively when they are used. In fact, one of the most effective ways to manage our immersion in bad information is simply to delay our response. To create a healthy space – in terms of time, emotions, and reflexive thinking – between the initial information we are receiving and how we choose to react to it. It’s a lot like creating space between other kinds of reflexive reaction. For example, if someone aggressively shoves me out of their way to cut past me in line, I might feel a reflexive urge to shove them back, or grab hold of them, or yell out “Hey, you can’t do that!” But if I instead insert a pause in my reaction, take a calming breath, and reflect for a moment about how best to respond, I can short-circuit my own visceral reactivity. Dealing with bad information can benefit from the same kind of patience and self-discipline.

Of course, being well-informed is also highly advantageous, so that when we are presented with partial truths, logical fallacies, or deceptive arguments we can more easily dismiss them

because we know what the actual truth is. Amid today’s 24/7 fire hose of mass media – and with digital devices as our constant companions, delivering this firehouse

with algorithmic amplification designed to keep our interest – the deluging clamor for our attention can be very challenging to manage.

So here are some helpful ways to buffer ourselves from the onslaught of such unfiltered, often questionable information:

1.

Be proactive in how information is consumed. For example, avoid remaining logged into social media or receiving social media notifications on your digital devices. If we allow algorithms to decide what information we should receive, then most research indicates (see

References and Resources) that we will receive what provokes our emotional engagement with that social media platform. Why? Simply because more engagement from us results in more ad revenue for those companies. This, in turn, results in what researchers call “computational propaganda.” So instead, if we deliberately choose to seek out specific information more proactively, we can protect ourselves from these profit-driven algorithms.

2.

Be proactive in our selection of information sources – and even then, check the facts. This can take some effort to figure out, but eventually we can gather together a number of sources that provide high quality, factual information about our areas of interest. One way to vet the bias and factuality of potential news sources is

https://mediabiasfactcheck.com/. And for reliable, in-depth research on many cultural and political issues, we can consult

https://www.pewresearch.org/. To verify questionable information, I recommend consulting

http://snopes.com/,

https://www.politifact.com/, or

https://www.factcheck.org/. And to appreciate how money intersects with politics in the U.S.,

https://www.opensecrets.org/ is an excellent resource.

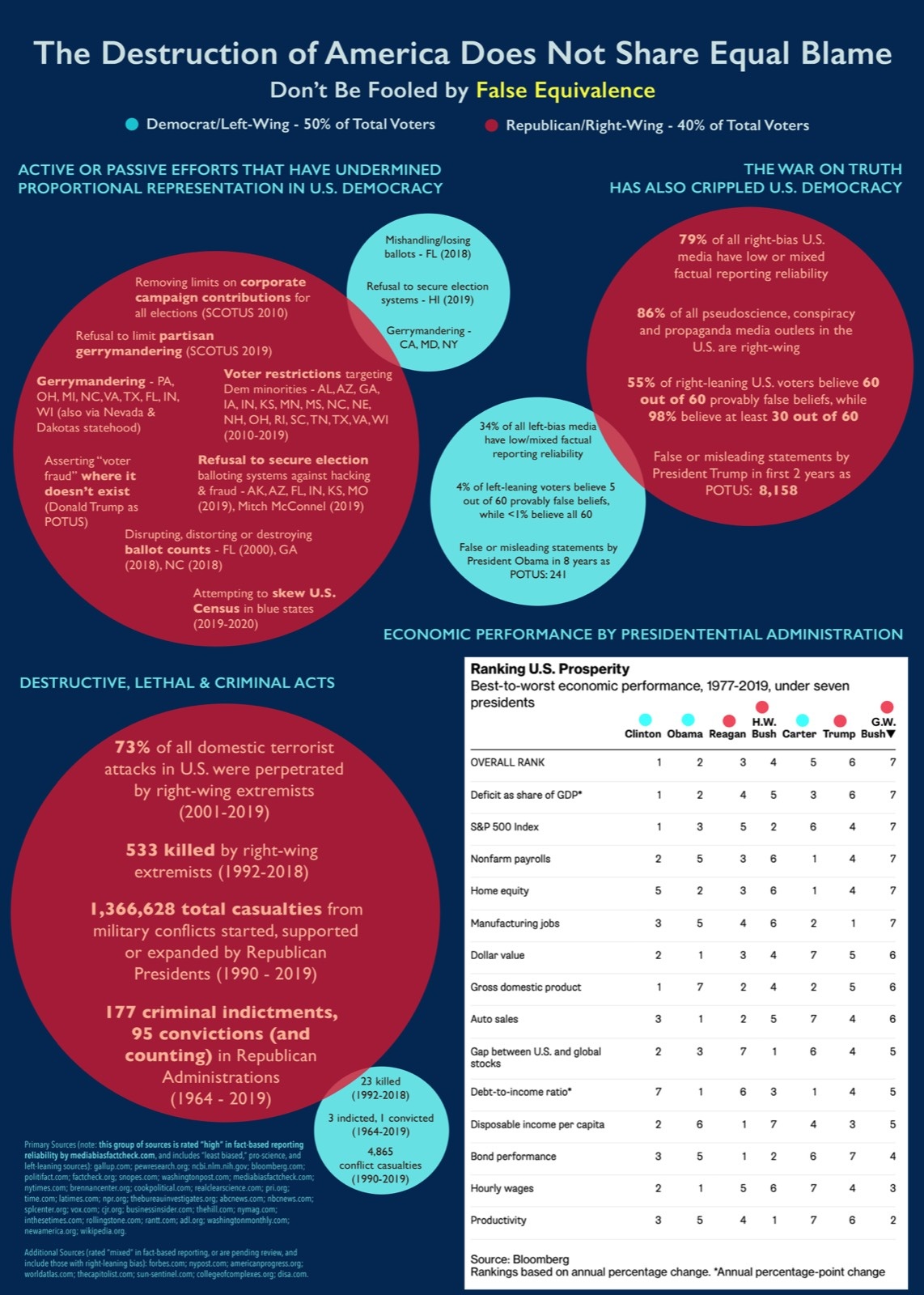

In terms of the current political landscape in the U.S.A., it can quickly and easily be confirmed (see

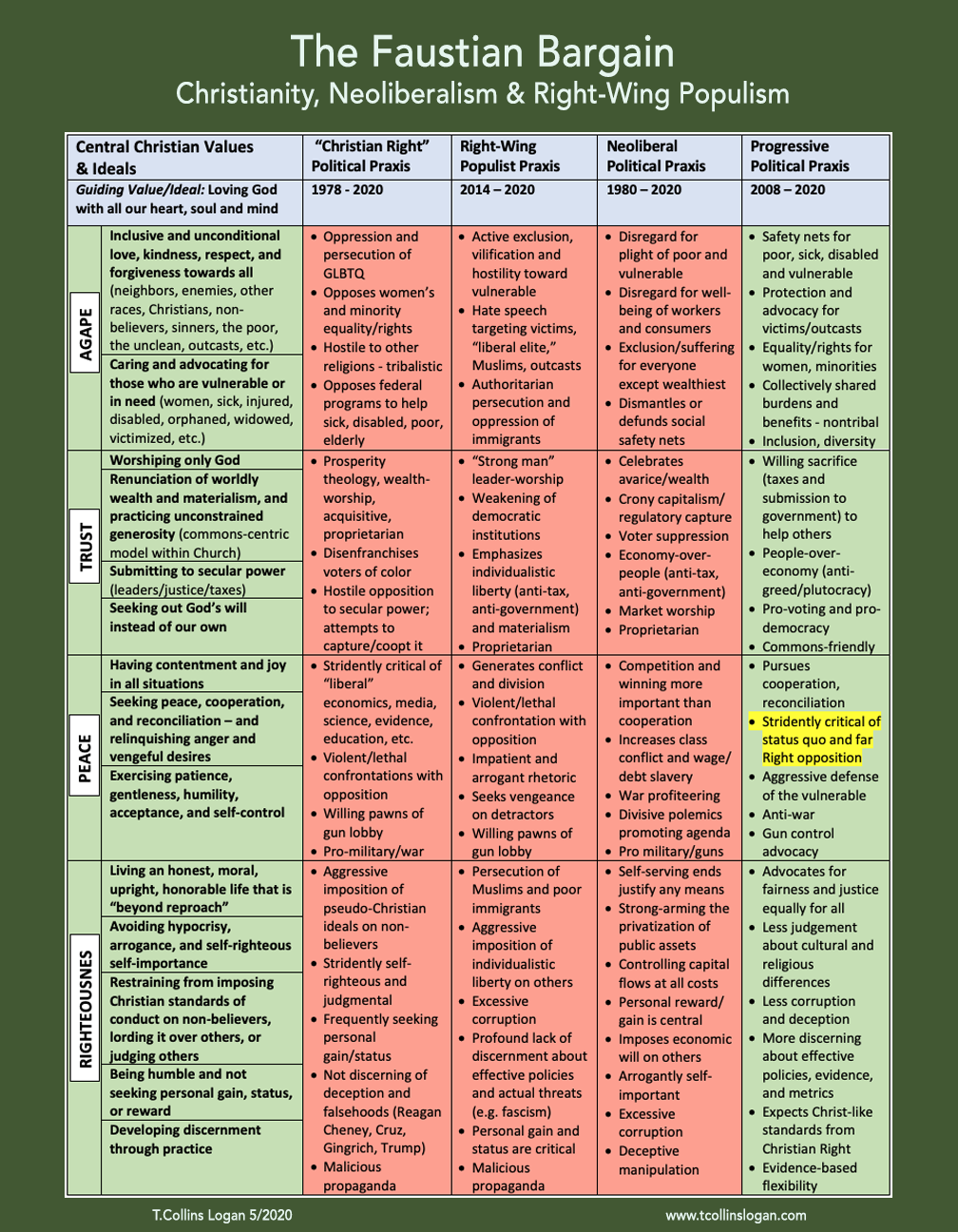

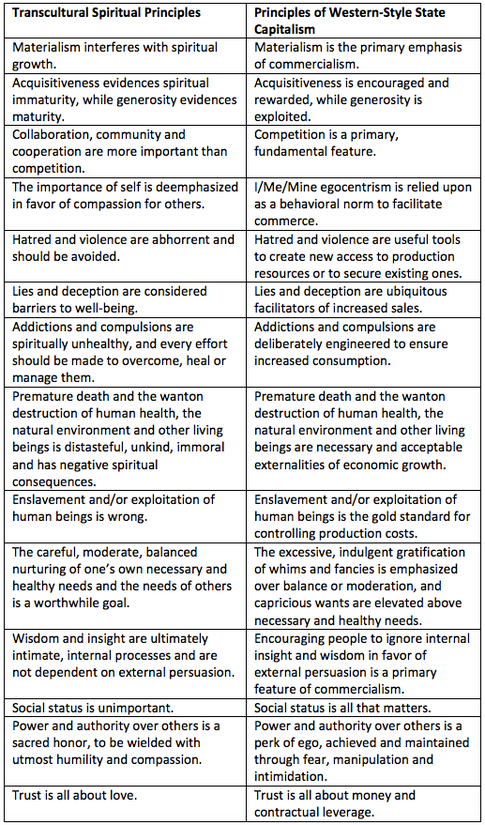

References and Resources) that the most prolific perpetrators of bad information practices are conservative pundits; the Republican Party and its political candidates; right-leaning U.S. media, bloggers, think tanks, and talk-show hosts; the official state-run media of Russia and China; and the efforts of social media troll farms and other “active measures” maintained by those same countries. Of course, you will want to evaluate and verify these claims yourself, but I think it is important to call out the most nefarious and destructive influences in U.S. politics right now.

Has this always been the case? With respect to Russia, this has definitely been the case since the Soviet era, but China seems to be a relative newcomer to the media-shaping game. Regarding the GOP in the U.S., it hasn’t always been this bad. In my opinion there have previously been reputable and responsible conservative-leaning media and pundits in the U.S. that would have called into question many of the claims being made by Republicans today. At the same time, conservatives have also executed long-term, well-funded efforts to discredit inconvenient facts that threated corporate profits – often through relentless “

science skepticism” attacks (e.g. regarding tobacco risks, climate change, acid rain, pesticides, etc.). With equal fervor, conservatives have assaulted government programs and policies that protect consumers, workers, and the poor, usually with some flavor of fear mongering. These efforts include “

red scare” anti-socialist propaganda techniques, as well as amping up rhetoric over “culture war” hot button issues (gay marriage and transgender rights; abortion rights; family values; parents’ rights; etc.) to agitate and motivate the Republican rank-and-file.

Do Democrats and those on the political left use similar tactics to persuade and manipulate people? And are left-leaning media, think tanks, and pundits as prolific in their propaganda, misinformation, or disinformation? Again, you will want to research and confirm the realities for yourself. But currently, although the left-leaning side of the political spectrum has sometimes been guilty of using similar tactics, it would be a grossly exaggerated false equivalence to say that Democratic politicians fabricate lies at the same rate as Republicans – or that Democrats rely on misinformation, disinformation, and logical fallacies to the same degree as the GOP. Left-leaning think tanks also tend to approach issues in a more even-handed, evidence-based, and scientific way than conservative ones. And in this moment of history, mainly driven by the extraordinary antics of Donald Trump and his “MAGA” followers, the GOP has gone down a rabbit hole of creating its own alternative realities. We could even say that, to exemplify the most potent examples of every “bad information” technique outlined here, we need only observe the copious pedantic claims uttered by Mr. Trump and his political supporters and media pundits.

As just a handful of examples of what right-leaning America has consistently gotten wrong, yet promoted as “truth” in order to win elections, sell ads, and raise donations:

• Joe Biden really did win the 2020 election, and zero evidence has been presented to the contrary despite repeated lawsuits.

• Donald Trump really did break the law in the willful hoarding of classified documents after he left office – and no, his evasive and obstructive behavior regarding those documents goes far beyond anything Joe Biden, Hillary Clinton, or Mike Pence did by comparison.

• Climate change is a real, scientifically validated event, and not a liberal conspiracy.

• Immigrants had nothing to do with the decline in jobs or wages in the U.S.A. over the last few decades. Instead, it was mainly corporate greed and the natural consequence of those corporations seeking cheaper labor and resources abroad and automating production and services.

• Tax cuts have never “paid for themselves;” that is, conservative trickle-down economics has never helped the poor or working class, but only enriched the owner-shareholders of big business and other wealthy folks.

• Vladimir Putin is not an underdog victimize by “western aggression” who nobly aims to preserve Russia’s status in the world – he is a brutal, murderous, megalomaniacal dictator hell-bent on expanding his own political power and the economic and political influence of Russia so that he can increase his own personal wealth and that of the oligarchs who enable him.

• Obamacare has actually helped millions of people obtain health insurance who couldn’t do so previously, and has helped reduce health care costs overall. And there were never any government “death panels” triaging patient healthcare.

• Deregulation has not helped American consumers or saved U.S. industries – with very few exceptions, it has consistently hurt both.

• There were no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, and Saddam Hussein had zero ties to the terrorists responsible for 9/11.

• Neither the recent escalation of inflation, nor the ballooning federal deficit, can be laid at the feet of Democrats or Joe Biden. While the legislation and executive policies of both parties have certainly contributed, the lion’s share of irresponsible spending, overly aggressive tax cuts, and disastrous economic and public health policies contributing to both inflation and the federal deficit can be laid squarely at the feet of Republicans – and indeed Donald Trump.

It is therefore not surprising that the GOP is so profoundly committed to false narratives and misinformation –

because the facts on the ground make them look really bad.

But 70+ million voters in the U.S. continue to be utterly conned and hoodwinked into believing these lies and many more – and into consistently voting against their own expressed values and best interests.

These are truly extraordinary times.

References and Resources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Propaganda_techniques

https://edu.gcfglobal.org/en/problem-solving-and-decision-making/logical-fallacies/1/

https://guides.lib.uiowa.edu/c.php?g=849536&p=6077643

https://www.grammarly.com/blog/logical-fallacies/

https://www.propwatch.org/propaganda.php

https://demtech.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2017/06/Casestudies-ExecutiveSummary.pdf

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/article/radical-ideas-social-media-algorithms/

https://level-7.org/Challenges/Opposition/conspiracy/

https://www.britannica.com/topic/big-lie

https://realmajority.us/files/stacks-image-d301f1f-1142x1600.jpg

https://level-7.org/Challenges/Opposition/

https://level-7.org/Challenges/Neoliberalism/

https://mediabiasfactcheck.com/

https://www.politifact.com/factchecks/2009/apr/01/cato-institute/cato-institutes-claim-global-warming-disputed-most/

https://level-7.org/Challenges/Neoliberalism/Attacks_On_Science/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Scare

https://www.vanityfair.com/news/politics/2014/11/conservative-nonsense-political-history

https://www.politico.com/news/2022/05/27/inflation-blame-game-sorting-out-the-culprits-00035712

https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2019/10/03/republican-tax-cuts-fail-record-debt-and-inequality-gap-column/3833546002/

https://www.budget.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/GOP%20Policies%20Caused%20the%20Deficit%20REPORT%2010-15-18.pdf

https://www.politico.eu/article/vladimir-putin-war-criminal-inhumanity-syria/

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/mar/24/republicans-parents-rights-education-culture-war

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_war

To understand what I mean by "intersectional disempowerment,"

To understand what I mean by "intersectional disempowerment,"  So a guy goes to a car dealership, and the salesman convinces him that this one car he’s interested in gets 50 mpg, does 0–60 in 4 seconds, and has a 5-year worry-free warranty. The dealership has one in a sweet metallic red, and so the guy buys it. He loves the car. Shows if off to his friends. Sometimes he just drives it around town for no other reason than because he’s enjoying driving it so much. But pretty soon he realizes that the salesman was…let’s say not quite telling the truth about the car. It only gets 15 mpg. It does 0–60 in about 7 seconds. And when the fuel pump quits after just two months…it turns out the “worry free” warranty doesn’t cover that (or much else that is likely to fail on the vehicle). The thing is, though, he still really loves the car. He’s willing to deal with all the problems because he still enjoys the pure pleasure of driving it around. Even after the dash instruments start failing one by one. Even after the timing belt breaks after 50K miles and the engine requires a total rebuild. Even after the chrome flakes off of all the detail work. Even after the squeaks all around the car get so loud that he can’t drown them out anymore with the car’s underpowered stereo system. This has been a pretty a common American experience. And the thing is, getting angry at politicians or one political party isn’t going to fix this situation - because it has nothing to do with them. The guy should have done his research. He should have listened to some friends who told him to avoid this particular brand of car. He should have been more careful and thoughtful and maybe not believed a salesman who just wanted to make a quick buck. But he didn’t. And he has no one to blame but himself. But…instead of owning up to his mistakes and admitting he was hoodwinked, the guy is furious with anyone who points out he was deceived, or corrects him for trying to blame his bad choices on “government regulation,” or tries to explain that the problems with his car really have nothing to do with unions, but instead were decisions made in corporate board rooms so that shareholders could line their pockets with just a little more profit. But the really sad thing is that, when the car finally breaks down completely after 100K miles, guess where this guy goes to buy another? The same dealership? The same salesman? A later model of the same shitty car…? No way! He’s finally “wised up” and gone to the competing dealership across the street, where the salesman welcomes him with open arms and convinces him to buy the latest model of THAT brand…which gets 50 mpg, does 0–60 in 4 seconds, and has a 5-year worry-free warranty (all of this isn’t true, just as it wasn’t the last time, but he doesn’t check the facts…). And so he buys the car - without doing the research, or listening to his friends, or questioning whether the salesman is telling the truth. And as he drives away, he shakes his fist out the car window at the dealership where he bought his first car, yelling “This is my ‘fuck you’ PROTEST VOTE!” So…really, what’s the point of trying to listen to the concerns of such a mindless, irrational consumer who is so easily and perpetually hoodwinked by lies and deceptions? I mean, really it’s on him to recognize his own mistakes, and to take responsibility for all the bad stuff that has happened to him. And until he takes responsibility and stops blaming others for his problems…well, things are not going to change. Not for him, and not for anyone else like him in America.

So a guy goes to a car dealership, and the salesman convinces him that this one car he’s interested in gets 50 mpg, does 0–60 in 4 seconds, and has a 5-year worry-free warranty. The dealership has one in a sweet metallic red, and so the guy buys it. He loves the car. Shows if off to his friends. Sometimes he just drives it around town for no other reason than because he’s enjoying driving it so much. But pretty soon he realizes that the salesman was…let’s say not quite telling the truth about the car. It only gets 15 mpg. It does 0–60 in about 7 seconds. And when the fuel pump quits after just two months…it turns out the “worry free” warranty doesn’t cover that (or much else that is likely to fail on the vehicle). The thing is, though, he still really loves the car. He’s willing to deal with all the problems because he still enjoys the pure pleasure of driving it around. Even after the dash instruments start failing one by one. Even after the timing belt breaks after 50K miles and the engine requires a total rebuild. Even after the chrome flakes off of all the detail work. Even after the squeaks all around the car get so loud that he can’t drown them out anymore with the car’s underpowered stereo system. This has been a pretty a common American experience. And the thing is, getting angry at politicians or one political party isn’t going to fix this situation - because it has nothing to do with them. The guy should have done his research. He should have listened to some friends who told him to avoid this particular brand of car. He should have been more careful and thoughtful and maybe not believed a salesman who just wanted to make a quick buck. But he didn’t. And he has no one to blame but himself. But…instead of owning up to his mistakes and admitting he was hoodwinked, the guy is furious with anyone who points out he was deceived, or corrects him for trying to blame his bad choices on “government regulation,” or tries to explain that the problems with his car really have nothing to do with unions, but instead were decisions made in corporate board rooms so that shareholders could line their pockets with just a little more profit. But the really sad thing is that, when the car finally breaks down completely after 100K miles, guess where this guy goes to buy another? The same dealership? The same salesman? A later model of the same shitty car…? No way! He’s finally “wised up” and gone to the competing dealership across the street, where the salesman welcomes him with open arms and convinces him to buy the latest model of THAT brand…which gets 50 mpg, does 0–60 in 4 seconds, and has a 5-year worry-free warranty (all of this isn’t true, just as it wasn’t the last time, but he doesn’t check the facts…). And so he buys the car - without doing the research, or listening to his friends, or questioning whether the salesman is telling the truth. And as he drives away, he shakes his fist out the car window at the dealership where he bought his first car, yelling “This is my ‘fuck you’ PROTEST VOTE!” So…really, what’s the point of trying to listen to the concerns of such a mindless, irrational consumer who is so easily and perpetually hoodwinked by lies and deceptions? I mean, really it’s on him to recognize his own mistakes, and to take responsibility for all the bad stuff that has happened to him. And until he takes responsibility and stops blaming others for his problems…well, things are not going to change. Not for him, and not for anyone else like him in America.