A POWERFUL REMEDY

The tragedy that occurred at the July 13th Pennsylvania rally is one more heartbreaking indicator of the spiraling crisis in America's body politic. It is unfortunate evidence that our collective moral compass continues to be crippled and distorted by angry, hateful political rhetoric. By rhetoric that seeks to defame and ridicule political opponents, promote baseless conspiracy theories, and wantonly encourage political violence – all in service to purely political ends. Before any other considerations, this angry and hateful rhetoric has to stop. Yes, there are other critical challenges to consider, other legitimate sources of grievance, and other serious fractures in civil society that must be healed. But it is a hateful, misleading, and demeaning polemic – issued constantly by pundits and politicians and then amplified across our media – that has too often become the spark that ignites flames of murderous rage. Our only bulwark against this manipulation is to demand that it end right now. Across the political spectrum, and from all corners of the media, this must be our unwavering ultimatum and committed call to action. A unity of moral clarity to reject hateful lies may be our only hope to avert a rapidly worsening, maliciously perpetuating political calamity.

This is an interesting question, and yes, there are a lot of examples of this occurring. One that springs to mind is the devolution of classical liberalism. Concepts of “liberty” and “fee markets” championed by proponents of classical liberalism in the 17th and 18th centuries were initially dependent on a strong civil society, but became more and more distorted and disconnected from that prerequisite over time. By the late 18th thorugh early 20th centuries, the initial ideas of a strong civil society with “good government” (Adam Smith) as a counterbalance to corporate malfeasance, capture of government by the wealthy, and abuse and exploitation of workers were completely abandoned by those claiming to be the disciples of classical liberalism (such as the authors of the “Austrian School”). By the time Milton Friedman and the Chicago School came into vogue, the wanton abandon for individualistic enrichment and empowerment had completely discarded any concerns at all for civil society, and actually encouraged corporate capture of government and other characteristics of crony capitalism in order to amplify self-enrichment. Randian objectivism then just added fuel to the same solipsistic fire. “Laissez faire” evolved into a sort of joke that every credible economist and social scientist understood to be a toxic delusion. This is how we arrived at what we call “neoliberalism” today.

This is an interesting question, and yes, there are a lot of examples of this occurring. One that springs to mind is the devolution of classical liberalism. Concepts of “liberty” and “fee markets” championed by proponents of classical liberalism in the 17th and 18th centuries were initially dependent on a strong civil society, but became more and more distorted and disconnected from that prerequisite over time. By the late 18th thorugh early 20th centuries, the initial ideas of a strong civil society with “good government” (Adam Smith) as a counterbalance to corporate malfeasance, capture of government by the wealthy, and abuse and exploitation of workers were completely abandoned by those claiming to be the disciples of classical liberalism (such as the authors of the “Austrian School”). By the time Milton Friedman and the Chicago School came into vogue, the wanton abandon for individualistic enrichment and empowerment had completely discarded any concerns at all for civil society, and actually encouraged corporate capture of government and other characteristics of crony capitalism in order to amplify self-enrichment. Randian objectivism then just added fuel to the same solipsistic fire. “Laissez faire” evolved into a sort of joke that every credible economist and social scientist understood to be a toxic delusion. This is how we arrived at what we call “neoliberalism” today.

There are many other examples of this sort of bizarre distortion of first principles in favor of grossly self-serving and destructive “opposites” — often ones that somehow retain the same name. Christianity is a potent poster child. Democracy is another. Hegelian dialectics, Existentialism, concepts of patriotism and nationalism…there seem to have been many such flip-flops over the years, where what was claimed to arise out of certain concepts, practices, and ideals ended up representing countervailing antagonism to those very same original principles. This seems to have been a very common pattern throughout human history, alas.

My 2 cents.

A morally mature adult owes society their commitment to maintaining that society in prosocial ways. After all, we owe everything we are — absolutely everything — to the civic institutions, rule of law, cultural expectations, economic stability and opportunity, political freedoms, human rights, educational opportunities, and other supportive structures that society provides. These are what form our identity and sense of belonging, and offer us existential security and pathways to aspiration.

It is utterly absurd, immature, and profoundly selfish for anyone to assert that they “owe society nothing.” Such sentiments are caustic and destructive to the promises of freedom, agency, and happiness that developed societies aim to accomplish for all individuals. In the context of modern society, individualistic materialism has unfortunately devolved into a sort of narcissistic solipsism, and if that devolution continues it will not end well for either society or its individuals.

Now, it is also true that society can do harm — it can use institutional, economic, and cultural hierarchy to oppress and deprive some people of the very freedoms, opportunities, and agency that it secures for other groups. And this inequality is a real challenge that we must address, so that there is a realistically “level playing field” for everyone to achieve their potential. This is why I personally advocate for arrangements of political economy that diffuse and distribute both power and wealth, rather than allow them to become concentrated. We are a long way from accomplishing this in much of the world, but there is a way to achieve it. My thoughts on that in the link below.

http://www.level-7.org/

So a guy goes to a car dealership, and the salesman convinces him that this one car he’s interested in gets 50 mpg, does 0–60 in 4 seconds, and has a 5-year worry-free warranty. The dealership has one in a sweet metallic red, and so the guy buys it. He loves the car. Shows if off to his friends. Sometimes he just drives it around town for no other reason than because he’s enjoying driving it so much. But pretty soon he realizes that the salesman was…let’s say not quite telling the truth about the car. It only gets 15 mpg. It does 0–60 in about 7 seconds. And when the fuel pump quits after just two months…it turns out the “worry free” warranty doesn’t cover that (or much else that is likely to fail on the vehicle). The thing is, though, he still really loves the car. He’s willing to deal with all the problems because he still enjoys the pure pleasure of driving it around. Even after the dash instruments start failing one by one. Even after the timing belt breaks after 50K miles and the engine requires a total rebuild. Even after the chrome flakes off of all the detail work. Even after the squeaks all around the car get so loud that he can’t drown them out anymore with the car’s underpowered stereo system. This has been a pretty a common American experience. And the thing is, getting angry at politicians or one political party isn’t going to fix this situation - because it has nothing to do with them. The guy should have done his research. He should have listened to some friends who told him to avoid this particular brand of car. He should have been more careful and thoughtful and maybe not believed a salesman who just wanted to make a quick buck. But he didn’t. And he has no one to blame but himself. But…instead of owning up to his mistakes and admitting he was hoodwinked, the guy is furious with anyone who points out he was deceived, or corrects him for trying to blame his bad choices on “government regulation,” or tries to explain that the problems with his car really have nothing to do with unions, but instead were decisions made in corporate board rooms so that shareholders could line their pockets with just a little more profit. But the really sad thing is that, when the car finally breaks down completely after 100K miles, guess where this guy goes to buy another? The same dealership? The same salesman? A later model of the same shitty car…? No way! He’s finally “wised up” and gone to the competing dealership across the street, where the salesman welcomes him with open arms and convinces him to buy the latest model of THAT brand…which gets 50 mpg, does 0–60 in 4 seconds, and has a 5-year worry-free warranty (all of this isn’t true, just as it wasn’t the last time, but he doesn’t check the facts…). And so he buys the car - without doing the research, or listening to his friends, or questioning whether the salesman is telling the truth. And as he drives away, he shakes his fist out the car window at the dealership where he bought his first car, yelling “This is my ‘fuck you’ PROTEST VOTE!” So…really, what’s the point of trying to listen to the concerns of such a mindless, irrational consumer who is so easily and perpetually hoodwinked by lies and deceptions? I mean, really it’s on him to recognize his own mistakes, and to take responsibility for all the bad stuff that has happened to him. And until he takes responsibility and stops blaming others for his problems…well, things are not going to change. Not for him, and not for anyone else like him in America.

So a guy goes to a car dealership, and the salesman convinces him that this one car he’s interested in gets 50 mpg, does 0–60 in 4 seconds, and has a 5-year worry-free warranty. The dealership has one in a sweet metallic red, and so the guy buys it. He loves the car. Shows if off to his friends. Sometimes he just drives it around town for no other reason than because he’s enjoying driving it so much. But pretty soon he realizes that the salesman was…let’s say not quite telling the truth about the car. It only gets 15 mpg. It does 0–60 in about 7 seconds. And when the fuel pump quits after just two months…it turns out the “worry free” warranty doesn’t cover that (or much else that is likely to fail on the vehicle). The thing is, though, he still really loves the car. He’s willing to deal with all the problems because he still enjoys the pure pleasure of driving it around. Even after the dash instruments start failing one by one. Even after the timing belt breaks after 50K miles and the engine requires a total rebuild. Even after the chrome flakes off of all the detail work. Even after the squeaks all around the car get so loud that he can’t drown them out anymore with the car’s underpowered stereo system. This has been a pretty a common American experience. And the thing is, getting angry at politicians or one political party isn’t going to fix this situation - because it has nothing to do with them. The guy should have done his research. He should have listened to some friends who told him to avoid this particular brand of car. He should have been more careful and thoughtful and maybe not believed a salesman who just wanted to make a quick buck. But he didn’t. And he has no one to blame but himself. But…instead of owning up to his mistakes and admitting he was hoodwinked, the guy is furious with anyone who points out he was deceived, or corrects him for trying to blame his bad choices on “government regulation,” or tries to explain that the problems with his car really have nothing to do with unions, but instead were decisions made in corporate board rooms so that shareholders could line their pockets with just a little more profit. But the really sad thing is that, when the car finally breaks down completely after 100K miles, guess where this guy goes to buy another? The same dealership? The same salesman? A later model of the same shitty car…? No way! He’s finally “wised up” and gone to the competing dealership across the street, where the salesman welcomes him with open arms and convinces him to buy the latest model of THAT brand…which gets 50 mpg, does 0–60 in 4 seconds, and has a 5-year worry-free warranty (all of this isn’t true, just as it wasn’t the last time, but he doesn’t check the facts…). And so he buys the car - without doing the research, or listening to his friends, or questioning whether the salesman is telling the truth. And as he drives away, he shakes his fist out the car window at the dealership where he bought his first car, yelling “This is my ‘fuck you’ PROTEST VOTE!” So…really, what’s the point of trying to listen to the concerns of such a mindless, irrational consumer who is so easily and perpetually hoodwinked by lies and deceptions? I mean, really it’s on him to recognize his own mistakes, and to take responsibility for all the bad stuff that has happened to him. And until he takes responsibility and stops blaming others for his problems…well, things are not going to change. Not for him, and not for anyone else like him in America.

An important questions, given today’s polarized landscape. Here are what I believe to be the top influences on people’s political beliefs:

1.Native intelligence.

2. Indoctrination and conformance of family, community, peers, coworkers, etc.

3. Level and quality of education.

4. Exposure to propaganda.

5. Native and learned critical thinking capacity.

6. Level of self-awareness.

7. Native tolerance for cognitive dissonance.

8. Native (or learned?) propensity to be motivated by fear rather than more positive emotions.

9. Need to belong to a group (and remain in lockstep with one’s “tribe”).

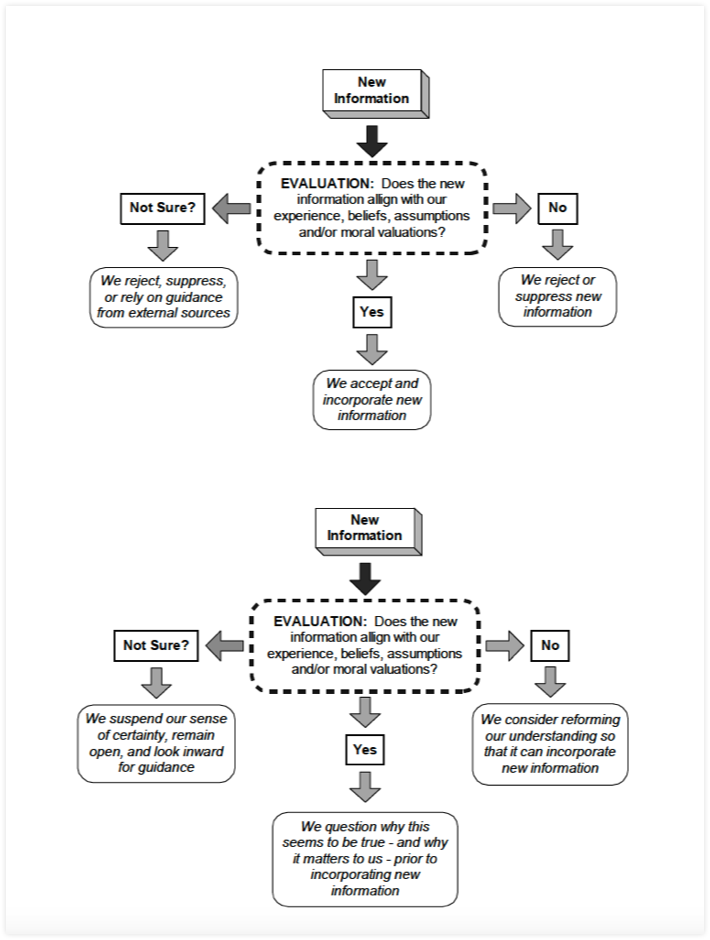

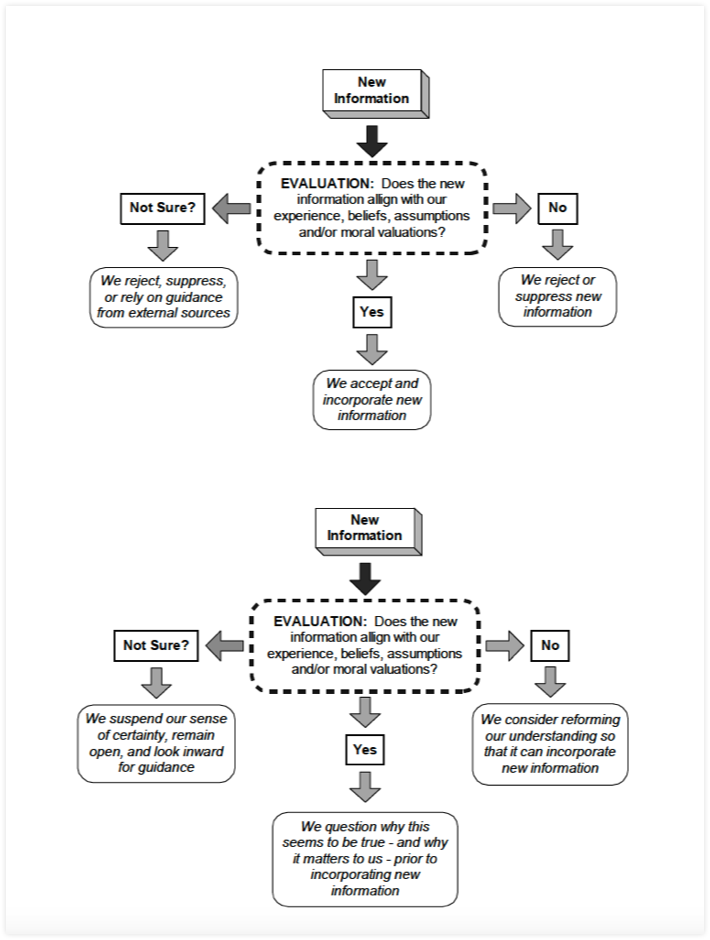

10. Native or learned ability to hold one’s own beliefs in a neutral space, and either revise or expand them when we encounter verifiable evidence — see diagram below.

11. An understanding and acceptance of science and the scientific method.

12. A native propensity to gravitate towards conspiracy theories.

My 2 cents.

The wrong-headedness of the latest SCOTUS ruling in favor of evangelical web designer Lori Smith is obvious to thoughtful Constitutional and Biblical scholars -- as it doesn't reflect the values, sentiments, and standards embodied in either document. The previous day's ruling on affirmative action at Harvard is likewise transparently oblivious to the racial realities of American culture and history. But the question to my mind is: Why is this happening? Why are folks who say they are committed to longstanding principles of the U.S. Constitution, the New Testament, and indeed civil society itself so eager to abandon those principles?

Well, I think it is all about fear. A deep, abiding terror that one's status and privilege of being "White and Right" is severely threatened by the natural, normal evolution of a morally maturing culture. It is a knee-jerk grasping after the power and wealth that will inevitably be lost as a more equitable arrangement of civil society is achieved.

And I don't see an end to that grasping. As long as this fear-powered conservatism energizes our electorate and our government officials, these irrational and hypocritical patterns will continue to amplify themselves. What the U.S. Constitution and the New Testament actually promote are concepts like equitable justice, inalienable and universal human rights, the criticality of a strong and democratic civil society, and the unfailing power of a generous and accepting spirit, a reflexive willingness to help others, and an unconditional compassion for our fellow human beings.

Will the overarching principles of love and equality, so venerated by some previous generations, prevail...? Or will we continue to slide backwards into selfishness and prejudice?

Well I suppose we will see how folks decide to vote in the upcoming 2024 elections and beyond...and who decides to abdicate their responsibilities and not vote at all.

Thank you for the question. Here are what I believe are some contributing factors that have gained increasing prominence in the past couple of decades:

1. A deliberate, carefully planned effort on the part of political activists, think tanks, and corporate media to divide, polarize, and demonize across the political spectrum in order to secure votes, increase campaign contributions and media viewership, and secure political status. It is much easier to appeal to fear and anxiety, play the blame game, and energize “Us vs. Them” polemics than to thoughtfully explore nuanced political philosophy and policy positions.

2. A downward spiral of biased media reporting that was instigated by ending the Fairness Doctrine in 1987. As a consequence of that very ill-informed decision, consumers of news media are simply often not presented both sides of the argument on political issues in any meaningful or reasonable way.

3. Social media echo chambers, the illusory truth effect, and consequent groupthink. When algorithms and like-minded groups of users amplify extreme, biased, and often false information that confirms their worst fear and mistrust, there is no longer room for discussion. Political topics become too highly charged with emotional rhetoric to allow moderating (or even true) viewpoints.

4. An unfortunate dumbing down of the U.S. voting public. There are likely a lot of factors contributing to this — poor nutrition, increased collective stress and anxiety, incomplete education, epidemic levels of ADHD, cultural opposition to “intellectualism,” etc. — but it is increasingly obvious that a lot of folks cannot reason critically at all, and instead quickly race down a rabbit hole of logical fallacies and contradictory assumptions.

5. Overwhelming input streams that folks often just don’t know how to manage, leading to feeling paralyzed, confused, and consequently more vulnerable to the influencing factors listed above. For example: way too much information funneled at all of us 24/7 from all directions at once; increasing complexity in nearly every decision we need to make; equally increasing pressure to make important decisions at much higher quantities and at much faster rates than many previous generations; accelerating technological and cultural changes that are increasingly difficult to track, let alone accept or fully incorporate on cultural and interpersonal levels.

6. A consumerist culture than encourages us to “bandwagon.” We are conditioned from early childhood to be guided by advertising and cultural norms that basically say “Hey, you don’t need to have your own agency or be thoughtfully informed, instead you just need to buy this or that and we’ll solve all your problems for you.” This conditioning runs so deep in U.S. culture that many folks simply conform to the latest cultural fads — which often originate at the fringe extremes of the political spectrum — in order to feel a sense of belonging and empowerment.

7. State-funded disinformation from hostile foreign actors that takes advantage of all-of-the-above and makes them much worse to serve the agendas of that country.

My 2 cents.

When very large and powerful government institutions are not held accountable by a functional democracy, then those institutions will certainly run amok over the citizenry and compromise other freedoms and rights in civil society — including the right to vote. This has tended to happen either where citizens are apathetic about their participation in the democratic process (as has been the case in the U.S.A. for many decades), or in places where a populist strongman deliberately consolidates their own power and undermines democracy itself (as has been the case of late in places like Turkey, Russia, Hungary, India, and multiple nations in Africa and Latin America).

But if the democratic institutions and public participation in democracy are strong, and authoritarian/autocratic leaders are voted out of office before they can wreak substantial damage on civil society, then the size of the government is not relevant, IMO. In the U.S.A., where the government is very large, Trump’s elevation to POTUS definitely woke up the country in terms of stimulating a more passionate participation in democracy…and his being voted out after one term likely saved U.S. democracy. But the size of the U.S. government did not really play into these variables.

What is much more critical in the preservation of democracy is carefully mitigating large concentrations of wealth and power and their impact on democratic institutions. The greatest erosion of democracy in the U.S. can easily be laid at the feet of the largest corporations, corporate media organizations, and wealthy campaign contributors. Their level of interference with functional democracy in the U.S. is truly astonishing — and it’s getting worse. To appreciate how organized and extensive this interference is, take a look into the history of American neoliberalism,

which has relentlessly and systematically sought to consolidate wealth and power in the hands of as few people as possible (see link below), and effectively crippled democracy in the process.

https://level-7.org/Challenges/Neoliberalism/

https://freedomhouse.org/article/new-report-global-decline-democracy-has-accelerated

No, the tyranny of the majority is not an unavoidable weakness of democracy. In fact there are so many welll-practiced and time-proven ways to effectively diffuse and countervail this possibility that its ascendence is really the exception rather than the norm.

Successful mitigation includes things like:

1. Implementing subsidiarity, so that democratic decisions are diffused down to the community level. At the same time avoiding concentrations of centralized political and economic power becomes a critical countervailing strategy.

2. Ensuring the electorate is well-educated about its responsibility to govern for the good of everyone in society, and is operating at a level of moral maturity that reflexively supports and enhances this view.

3. Strengthening egalitarian rule of law, and egalitarian civil society generally, to support an equality of rights, opportunity, ability, and enforcement across society — all of which inherently aim to compensate for existing inequalities and at least attempt to level the playing field.

4. Institute truly independent checks and balances to ensure no single institution, governing body, or system has absolute authority over any aspect of society. Interestingly, one way to accomplish this is by implementing direct democratic controls over representative bodies as some constitutions allow.

Sadly, what has become much more problematic is the “tyranny of the minority,” where a smaller group that has gathered an inordinate amount of economic and political power to itself runs roughshod over democracy and civil society to maintain its own privilege, influence, and wealth.

My 2 cents.

Absolutely.

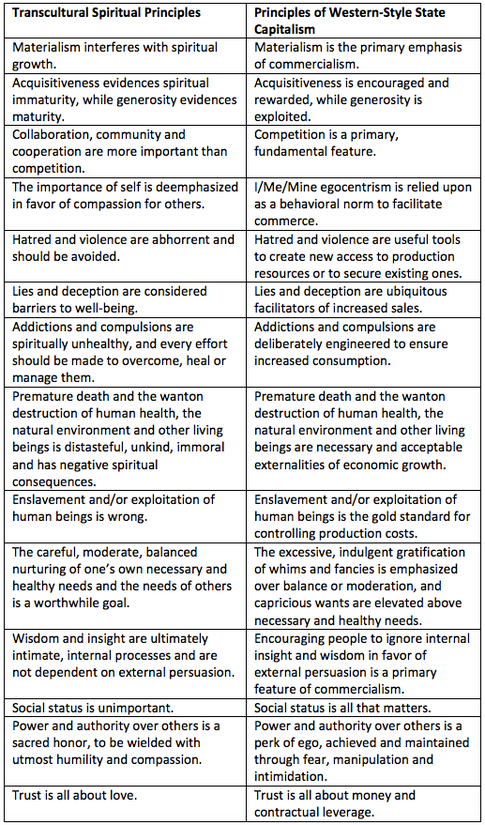

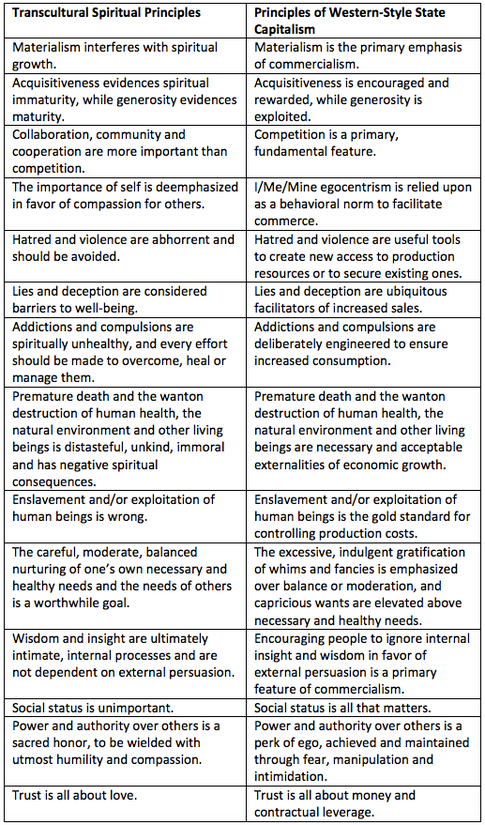

It’s difficult to summarize just how extensive the impacts of consumerism on the individual and society are. I think the easiest way to begin that conversation is to list some semantic containers that encompass negative aspects of consumerism. Three of the most well-defined containers are

economic materialism, conspicuous consumption, and

commodification. Here is a brief overview of each:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economic_materialism

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/conspicuous-consumption.asp

http://neolib.uga.edu/commodification.php

In essence, these three habits alone contribute to an accelerating amplification of deleterious “non-material” impacts on the individual and society, which include:

1. The general

devaluing of human trust relationships in favor of transactional relationships — in other words, the eroding of interpersonal trust and, by extension, community and societal trust. This of course expands into regional, national, and international attitudes and practices as well, so that we come to rely solely on transactional evidence of trust, rather than a more cultural cooperation, interdependence, and exchange.

2.

The “externalization” of all personal and collective priorities, growth, meaning, and power, rather than development of internal qualities. For example, the belief that one’s possessions, material wealth, and physical characteristics are more important in attracting friends and romantic partners than internal qualities like honesty, compassion, empathy, generosity, and so forth. Or that one’s self-worth is likewise dependent on consuming and owning material things, rather than on the qualities of one’s own character. Or that social status and popularity propelled by such externals are more important than the quality and depth of our interpersonal relationships (that is, the shared feelings of connection and commitment our friendships evoke). This externalizing attitude is then expanded to include all of society and our national identity: instead of demonstrating good citizenship (in our community, or as a nation in global affairs) we become more concerned with clawing after power, status, and control, as those are our “external” proofs of success in the world…rather than the quality of relationship our nation has with other nations.

3. The overall

cheapening of human life and disrespect for our fellow human beings — or anything in life that doesn’t achieve sufficient “exchange value.” This is perhaps the most egregious impact of consumerism, when our prioritization of acquiring material things, reliance on consumption for social status, and projection of material valuation and standards on others erodes our fundamental respect and compassion for others and any valuations of the

intangible benefits of being live. Consider that commodification intentionally erases the constructive societal value of everything in favor of its “exchange” value in the marketplace — what better way is there to cheapen and denigrate the intrinsic value of everything in life (art, love, joy, intimacy, humanity, compassion, etc.) than to force everything into tidy, sterile boxes of monetary valuation? Paul Piff at UC Berkeley has done some interesting research related to this, documenting the negative impact of personal wealth on prosocial behaviors.

4.

An undermining of happiness as individuals and society as a whole. The vast majority of long-term research in this arena has demonstrated that enduring happiness does not rely on consuming or possessing material things. Instead, happiness is primarily dependent on strong interpersonal bonds with other people — and the deepening trust, intimacy, and contentment this produces. Consuming things does stimulate short bursts of dopamine, but not oxytocin, which loving human relationships stimulate. Interestingly, healthy oxytocin levels actually reduce our need to consume calories. Perhaps it also reduces our “need” to consume other material things….?

5.

Interference with spiritual, emotional, and moral development (again as individuals and society as a whole). This is a more subtle principle, and I can only speak from personal observation and experience on this matter. A materialism-consumerism orientation to the world will reliably retard our spiritual, emotional, and moral growth, keeping us “infantilized” and forever dependent. This is really an extension of the “externalization” principle alluded to earlier, but with a much more insidious and profound impact. I think this is why nearly every spiritual tradition encourages relinquishing our acquisitiveness and our trust in material possessions for any sense of self-worth or existential security. If we can’t learn to “let go” of our need to acquire and possess stuff, we will never cultivate the internal growth necessary to be spiritually, emotionally, and morally mature. Why? The mechanisms become intuitively obvious to anyone who has practiced such “letting go” with persistent discipline, but I would equate the process to

a child’s individuating from their parents. There is a quality of interior self-sufficiency and an independence of will that is unattainable if we remain attached to material things. We simply cannot become mature adults if we are forever suckling at the teat of consumerism.

Some additional reading related to this topic, in no particular order:

https://www.academia.edu/4233302/The_Stupefaction_of_Human_Experiencehttps://www.academia.edu/4233690/A_Mystics_Call_to_Action

https://www.level-7.org/resources/Developmental_CorrelationsV2.pdf

My 2 cents.

An “Us vs. Them” mentality amplified by regressive cultural norms, for-profit media (including social media) that relies on provoking extreme emotional reactions in order to make money, disinformation campaigns funded by both U.S. corporations and foreign governments in order to consolidate power or disrupt threats to power, underlying and toxic levels of individualism and materialism inherent to commercialistic culture, technologically and commercially driven change occurring at a breakneck pace that inherently alienates folks with non-adaptive constitutions, demographic shifts that also make many people feel uneasy or insecure about their assumed position of privilege in society, exponential complexity and interdependency across all of society that is disorienting and destabilizes cultural traditions and norms, and an unsustainable economic system that has been breaking down for some time….

In other words:

a perfect storm.

All of these pressures combine to create real tension and pain across multiple segments of society, and exacerbate differences in how people react to that tension and pain. For one type of group in particular, the disruption and discomfort is very acute — those with a naturally tribalistic, fear-based, morally immature disposition (i.e. a strong “I/Me/Mine” or “We/Us/Ours” moral bias). There is a growing visceral and irrational reactivity among this group, which mainly inhabits the conservative end of the political spectrum (about 35% of conservatives) but is also present in the liberal/progressive end of the political spectrum (about 14% of progressives). These folks are unfortunately mired in low emotional and general intelligence, high levels of willful ignorance, reflexive greed, racial and cultural prejudices, fear, pathological selfishness, and an enduring sense of victimhood and self-righteous indignation. I personally have begun to wonder if the amplification of these negative traits are at least partly the result of epigenetic breakdown of the human genome as a consequence of environmental toxins and stress — but that is another, more challenging topic to explore another time.

But of course such traits are being manipulated by the aforementioned media and disinformation campaigns, along with commercialistic culture, which use them to energize a collective Dunning-Kruger effect and illusory truth effect that result in automatic consumption of untruths, snowballing extremist views, conspiracy thinking, and an increasingly volatile and polarized mindset that unfortunately tends to vote, consume, and donate money entirely contrary to those people’s own best interests, and in contradiction to their deeply held and frequently expressed values.

For more on all of this, please read:

https://level-7.org/Challenges/Neoliberalism/https://level-7.org/Challenges/Opposition/

https://level-7.org/Challenges/Capitalism/https://level-7.org/Challenges/Neoliberalism/Attacks_On_Science/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illusory_truth_effecthttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunning–Kruger_effect

My 2 cents.

Freedom is a type of cultural currency — a coin with two sides.

On one side of the coin is insulation from economic insecurity, acute lack of opportunity, and deprivation of social capital. I call this

“freedom from poverty,” where poverty comes in many forms but always has the same effect:

it robs us of the operational capacity to exercise most freedoms, and interferes mightily with exercising liberty. Another way to describe this is for everyone in society to be provided the same existential foundations and available choices — a level playing field across many dimensions of life that liberates us from being oppressed and restricted in real terms.

The other side of the liberty coin is

collective agreement to support the liberty of others, regardless of who those others are and whether they are “just like me.” This equates a high level of tolerance and acceptance of differences between people. However, the presumption is that many core values are shared across all differences, so that this collective agreement is not too onerous, distasteful, or amoral. We agree to operate a certain way as a society so that everyone else’s freedoms are maximized. This is the basis of

the rule of law.

Good government’s role is to facilitate both sides of the freedom coin when society is not able to do so on its own. When societies are culturally immature — as is the case with the U.S.A where I live — they require a bit more involvement from government to create both freedom from poverty and an effective rule of law. When the citizenry is morally immature and generally ignorant, government intervenes to create “civil society” by bolstering these two arenas. Over time, as societies mature into a more morally advanced arrangement and all citizens acquire broader foundations of knowledge, government’s role can attenuate as both sides of the liberty coin become the de facto reality of cultural practices and standards; that is, civil society can be supported increasingly by perversive culture rather than by government.

The common denominator for all such arrangements is progressive democracy, where citizens have increasingly direct control over how both

freedom from poverty and

the rule of law are implemented in their community, region, and nation. Democracy becomes a sort of banking system that stores up and protects this wealth of liberty and regulates how it is exchanged and shared within society. But again, democracy can only be effective in this regard when citizens are maturing morally and accumulating sound knowledge.

How to effectively encourage, fortify, and enhance the moral creativity of society so that our “freedom coin” is actually increasing in value has been a long-term aim of my research and writing. For more on this and all-of-the-above, please see the resources below.

Prosociality

Level 7 Philosophy

The Goldilocks Zone of Integral Liberty

Private Property as Violence

My 2 cents.

I would say rarely if ever. Remember that the very definition of this term is (from Merriam-Webster): if “a desired result is so good or important that any method, even a morally bad one, may be used to achieve it…” The clear implication is that specifically morally questionable means are justified by a “good or important” end.

But that’s just hogwash. All intentions and subsequent actions must be guided by a moral framework, or morality just doesn’t exist. Folks will often rationalize immoral or destructive means to achieve a goal they believe is important — but rationalization is all they are engaged in, not serious moral reasoning. The value of an outcome is utterly compromised by such toxic self-justificaiton — the outcome cannot be evaluated in isolation from the means used to achieve it.

Imagine if you will the most beautiful sculpture ever created — let’s say it’s of a benevolent angel. The sculpture brings everyone to tears of awe when they see it, causes emotional wounds to heal, calms bitterness and hatred between angry combatants who enter into its presence, and even inspires people to perform profound acts of kindness and generosity after seeing it.

The problem? The sculpture is made from the skin, blood, and bones of a thousand children who were tortured and killed to provide those materials. Someone who confidently claims that “the end justify the means” could shrug that torture and murder of children off…but by any definition they would be considered a psychopath.

So when someone begins to tout that philosophy, be very wary. They are well on their way to amoral chaos or serious mental illness…if they haven’t already arrived there.

My 2 cents.

LOL. Really? Well let me first say that the door to much propaganda in the world today is something very sneaky, something called “reasonableness.” In the case of neoliberal market fundamentalists like Mankiw, that “reasonableness” is describing “principles of economics” that, taken individually and in (academic and ideological) isolation, may seem reasonable. In fact one could debate each of Mankiw’s principles ad nauseum, and still be operating within his ideological framework — because of how he restricts the scope of the conversation. You see the problem? If you ask me “what are the principles of a stable romantic relationship,” I could respond: “Well, first off both people in the relationship need to buy the right kind of clothing. Second, they both need to listen to the same kind of music. Third, there needs to be a clear, preexisting understanding of what each person’s role should be….” And so on. And I could keep elaborating on these “principles” as if they actually correlated with every dimension of a human relationship…when clearly they would not. They would, in reality, be confined by a very narrow perspective on relationship that I was effectively imposing on the conversation. And the more emphatically I insisted that nothing else need be included — while I actively excluded very important additional or alternate factors — the more I could perpetuate a discussion that is boundarized by my own biases. And that is precisely what Mankiw is doing…just like many neoliberals before him. I often flag this sort of behavior as ideologically fascist, with the poster child of the technique — in economics at least — being Milton Friedman.

That said, what issues do I have with Mankiw’s 10 principles themselves? That would be a very lengthy conversation. At a 10,000-foot level, I would say they are “half-truths that add up to delusional bupkis.” More specifically, behavioral economics has clearly demonstrated that consumers are not rational operators, and that principles 1–4 are not only oversimplifications, but actually distort or distract from the microeconomic dynamics that are really in play. Human decision trees are not analytically neat-and-tidy, they are messy, impulsive and emotional; and, in fact, marketing knowingly exploits that unstable irrationality to condition completely counterfactual, counterproductive, unhealthy, demeaning and dangerous consumption patterns in consumers. For crying out loud…this is obvious to anyone who observes or researches real-world consumer responses to corporate coercion and manipulation.

After 1–4, Mankiw gets a bit more sneaky with 5–7. He uses the phrasing “trade can,” “markets are usually,” and “governments can sometimes,” and of course we can’t really argue those points, because…well…they are in fact reasonable. Except…well…are they? It is when Mankiw elaborates on these points further (in his writings, etc.) that we see the depth of his blindness — how he does not appreciate or address the complex interdependencies involved, or the widely demonstrated externalities and causal chains, or in fact the well-established track record of what actually works in the real world…and what really doesn’t. This is where we can get lost in the weeds, but suffice it to say that Mankiw doesn’t begin to fully enumerate all of the inputs and outputs of trade, or the complex landscape of variables that influence those inputs and outputs, or, indeed, the disastrous consequences of what can fairly be described as “Mankiw-esque” market fundamentalist policies we have witnessed in the past. His ideas live in a bubble — applicable to what I call “a unicorn market,” one that has never and will never exist.

Principles 8–10, along with most of Mankiw’s thinking, are just more conceptual trickle-down from outdated classical economics. But (and this is pretty ironic IMO) unlike Smith, Ricardo et al, Mankiw fairly reliably excludes the common good from being part of serious deliberation. In other words, he drifts into the realm of laissez-faire that classical economists actually warned about. Where, as Smith wrote: “All for ourselves, and nothing for other people, seems, in every age of the world, to have been the vile maxim of the masters of mankind.” But are points 8–10 accurate in any way? Sure…again if you exclude all sorts of other factors, causes, variables, evidences, etc. that are critical to a complete macroeconomic picture, Mankiw’s points provide a partial, highly tailored framing of causal relationships. So, if a person ignores how markets actually function, the corruptive influences of crony capitalism, how boardroom decisions are actually made, why financialization has displaced production for massive wealth generation, why monopolies occur, where Keynes was proven correct (and what monetary policies actually work), why growth-dependent economies boom-and-bust, etc…and instead pines away for a juicy young unicorn to sate their every neoliberal appetite, well then: Mankiw is the porn for them!

Let me just call out one specific example of Mankiw’s delusional approach. His prescription for most resource allocation challenges is to privatize them — like many neoliberals, Mankiw believes private property is the panacea for all ills. However, Elinor Ostrom demonstrated in her common pool resource management research that the tragedy of the commons need not exist where self-organized, self-managed sharing of common resources is approached a certain way, and she goes on to enumerate observed principles that have been successful. Essentially, there are widely employed systems of access to and utilization of common resources around the globe that completely sidestep the tragedy of the commons without private ownership or government intervention. Hmmm. How could this be? In Mankiw’s unicorn universe, it can’t be, since there will always be free riders and excessive inefficiencies when privatization is absent. But again, Ostrom was just documenting what she observed in the real world, so Mankiw is just, well…wrong. Hence the nature of the problem with most of Mankiw’s thinking — and indeed most market fundamentalist thinking (i.e. Randian objectivists, anarcho-capitalists, individualist economic materialists, Austrian School evangelists, etc.).

My 2 cents.

Yes of course. Throughout human history innovation and social responsibility — which I would define more broadly as creativity and prosociality — have existed and thrived without the profit motive. In fact the profit motive interferes mightily with both more often than not.

On the one hand the profit motive channels innovation and creativity into a very narrow focus of only what increases profit, abandoning anything that doesn’t promise return on investment. For example, we often see real innovation crowded out by “cheaper and more efficient” forms of production and service delivery, because those types of innovation guarantee greater profitability. Most of the big leaps forward in more creative and life changing innovation, in fact, have arisen through academic and government research, by inventors fiddling in their workshop for fun, artists creating masterpieces for their loved ones, philosophers struggling to answer complex moral questions, or mathematicians solving challenging equations — all because that particular mountain was simply there to climb, not because they would make a buck off of it. The results were then put into production by for-profit companies who reap all the rewards from someone else’s creativity. The profit motive doesn’t have much at all to do with the innovation, just its mass production. This is the case with everything from cell phone technology to medical advances to major changes in the structure of society.

The profit motive has also long demonstrated it can often be at odds with social responsibility and prosociality. There have been countless instances where the profit motive has created oppressive or life threatening conditions and consequences for workers and consumers — and the history of capitalism has mainly been about civil society correcting those abuses (child labor laws, worker safety laws, consumer protections, environmental protections, strengthening democracy against cronyism and plutocracy, etc.). And the oppressive and exploitative conditions created by the profit motive have often threatened the stability, liberty, and thriving of civil society itself. Although it is true that capitalism and the profit motive have provided an extraordinary engine for productivity and economic growth, it has been civic institutions, democratic reforms, educational institutions, and the expansion of civil rights that have established or strengthened conditions that support creativity, innovation, social responsibility, and general societal cohesion — particularly in the face of a countervailing atomistic individualism and commercialistic materialism inspired by the profit motive.

This is not the narrative that the “market fundamentalist” or pro-capitalist folks appreciate or even understand. They are often blind to the antagonisms of liberty, creativity, and civil society that the profit motive has wrought.

But again, if we study the grand arc of human history, most of the greatest innovations, and the greatest evolutions in civil society itself, have been utterly divorced from the profit motive. Humans just love to create, to connect with each other and create community, and to build institutions and civic structures that support those impulses. The profit motive is tolerated because it has lead to a rapid expansion of material wealth and technological conveniences — it has facilitated creature comforts and material security. But it has also eroded society at the same time, which is why it has had to be constantly managed and constrained.

My 2 cents.

Thanks for the question. A few thoughts for your consideration….

1. I don’t think it was Murdoch’s intention to “discredit or destroy” the (rationalist, empiricist, volantarist, etc.) moral philosophies of her contemporaries. That really wasn’t her style IMO. Instead, I think she was just calling some basic assumptions of these modes of thinking into question — being skeptical of what we might describe as a scientism that rejects metaphysical and even multidimensional aspects of reality and consciousness. Murdoch mainly offers us an invitation to look at things more carefully, in order to see “things as they really are” with greater breadth and inclusivity.

2. Further, although Murdoch does rely heavily on Plato’s metaphors, they are really just a starting point for discussion rather than an endpoint; Plato’s cave, fire, and sun are merely a vocabulary of framing that permits her to expound more deeply on the nature of “the Good.” Plato’s terminology is a lever to help Murdoch accomplish some heavy lifting…not the object that is being lifted.

3. I think Murdoch intuited that something was amiss in contemporary assumptions regarding human rationality, human will, or a locus of consciousness fixated on the self (what we might call egoic consciousness) being able to adequately navigate moral complexity or fully comprehend or describe “the Good.” She further intuited that certain qualities of love were involved in both pursuit of that good, and in its apprehension and reification. And, perhaps most importantly, Murdoch intuited that, although “the Good” may sometimes seem ineffable or indefinable in purely rational terms, it is nevertheless discernible and obvious — and even reflexive — in the context of human relationships, choices and intentions when selfless love is in play.

4. Finally, Murdoch hints that the ego’s impedances to conceiving of and actualizing “the Good” may be the same barriers that rationalist/empiricist/volantarist philosophies encounter when navigating morality itself. I.e. that they are preoccupied with the fire in the cave, and have not yet ventured out into the sunlight — they are relying on false light to illuminate the indescribable.

I hope this was helpful.

It is heartbreaking for me to encounter responses to this question that sidestep discernment and wisdom around this issue. Sure, obviously history is written by the “winners.” Sure, folks at different ideological extremes have opposing views of what is “right,” while also expressing the same level of confidence in their views. Sure, people’s attitudes about behaviors, events and priorities change over time.

All of this is true. But the conclusion that we should, therefore, abandon all hope of perceiving or understanding “who is on the right side of history” seems to me a rather lazy, cynical, and irresponsible excuse for not paying better attention to the human condition and civil society — and becoming more educated about them. In fact, such casual surrender to willful or despairing ignorance seems to reflect the sort of solipsistic nihilism that has routinely gotten folks into trouble…

and indeed often places them on the “wrong” side of history.

So how do we discern who is on the right or wrong side of history? Of course we could begin with our own personal values hierarchy, but that wouldn’t be entirely helpful — in isolation, what do our own personal value or morals have to do with the larger arc of human history, after all? What we can do instead is look back over the history of human existence and civilization and track what the core characteristics of “right” and “wrong” have looked like, and observe how those tendencies have played out over time. Through that lens, we can assess who ends up occupying the “right” and “wrong” sides of history itself, and we can then attempt to project those standards and patterns onto current events.

Although initially requiring a lot of careful research, it’s a relatively simple exercise once the data is compiled. This process is in part what my book

Political Economy and the Unitive Principle sets out to do, and you can read it for free via the link provided here.

At the risk of oversimplifying, I’ll summarize the main points:

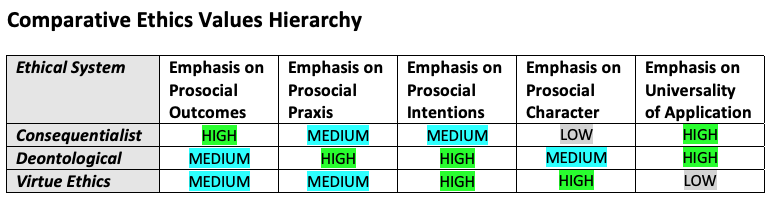

1. Humans are prosocial critters, and thier prosociality has been key to human survival and the evolution of civilization itself — and also relatively uniform in its expression in terms of promoted behaviors and social mores (sure, there is variability, but the broad strokes are the same).

2. There is also a predictable progression of the individual and collective moral maturity process that reflects ever-widening spheres of inclusion for our prosocial impulses (i.e. we include larger and larger spheres of interaction and relationship in our caring as we morally mature).

3. As long as conditions are supportive, that moral progression is a natural, easily observable phenomenon in individuals and across every society we know of…and continues in those around the globe today. However, that progression is not fixed, fast, orderly, or immune to regression…it is instead messy and organic, and often slow (hence we need remember the “long” part of “the arc of the universe is ***long***, but it bends towards justice”.

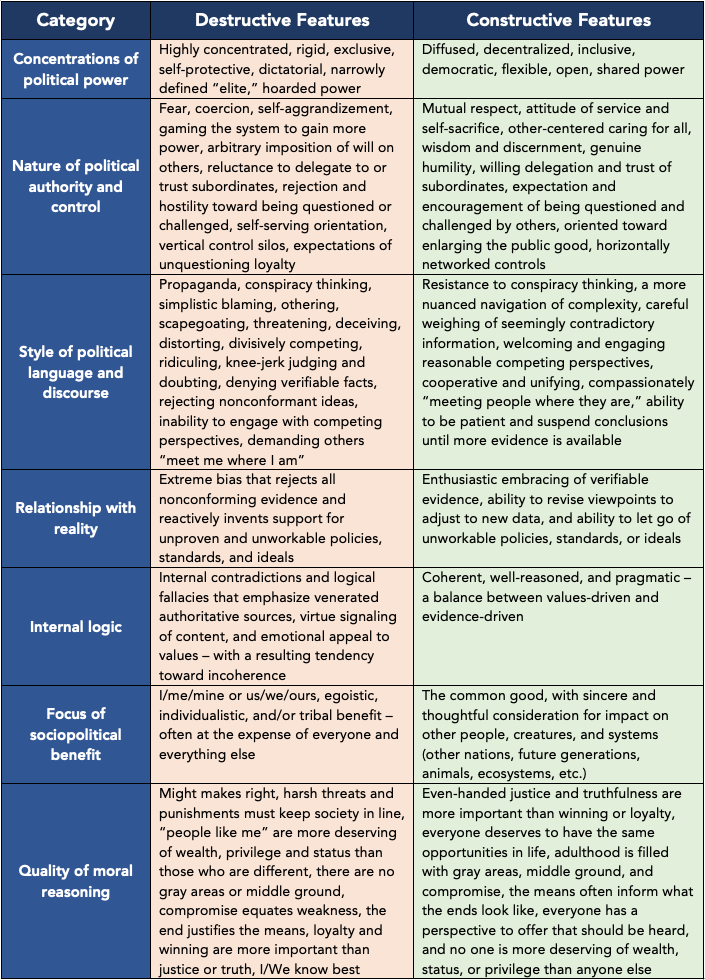

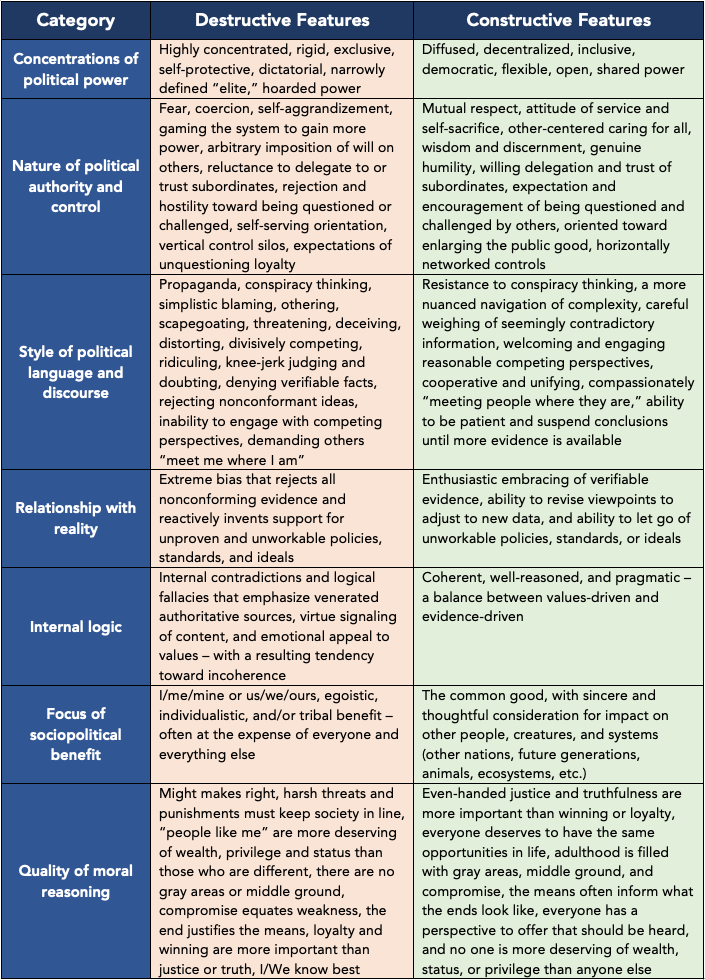

4. Despite the “messiness” of our moral evolution, it then becomes quite clear who or what is on the “right” or “wrong” side of history — it is simply a matter of mapping those people and events within a progression of prosocial characteristics. To that end, please see this chart:

https://www.level-7.org/resources/Developmental_CorrelationsV2.pdf

Lastly, those who have developed even a little bit in terms of their moral maturity will quickly recognize what is or is not prosocial in both modern times and history — that is, what is or is not beneficial to civil society over time. **However, this level of discernment and wisdom may seem mysterious or perplexing to those operating in the lower strata of moral development.** Those who aren’t as advanced shouldn’t be belittled for that (unless, perhaps, their arrogant willfulness demands it…), but instead encouraged to heal, mature, and grow.

For further reading, I would also recommend this essay:

The Goldilocks Zone of Integral Liberty

And for a deeper dive into my own theorizing about the nature of love — which is the basis of prosociality — and the human condition, please check out this book (also free to read):

True Love

My 2 cents.

That would be an almost accurate statement, yes. The challenge (as with almost all attempts at summarizing complex philosophy) is that Popper uses a lengthy, layered sequence of arguments to explain why utopian thinking is problematic — or rather, tends to lead to self-defeating outcomes. Essentially, he argues that it is impossible to fully anticipate or predict how humans will actually behave within a given utopian structure or system, and that, without the ability to modify or evolve such a structure or system in response to those unpredictable events, there will inevitably be unanticipated consequences that undermine the utopia. Which is why, he insists, utopian “central planning” will inevitably lead to totalitarian/authoritarian oppressions — thereby ‘choking its own refutations’ and any chance of healing itself and fulfilling its vision.

Whether this is a valid argument has a lot to do with one’s view of historicism — i.e. whether there is a predictable (at least in the broadest strokes) progression of human society over time — and whether it is at all possible to fully anticipate or accelerate that evolution. My own view is that both assumptions are valid, but that imposing a top-down hierarchical structure or system is the wrong way to go about encouraging change, and indeed can lead to the sorts of problems Popper identified (especially when there are no strong, resilient democratic institutions to check authoritarian tendencies). However, IMO it is possible to encourage societal evolution by facilitating and expanding what I call the “moral creativity” of society — that is, an environment that encourages moral maturation individually and collectively. This is, however, an organic grass roots process centered around community-level relationships, rather than a top-down program that can be imposed on people. You can read more about my thinking on this here:

https://level-7.org/Philosophy/Prosociality/

Thanks for the question. Here are some reasons why I think authoritarianism is on the rise:

1. White men have lost status in society. This is frightening. So, in their insecurity and fear, they turn to strongman leaders who seem like carnival mirror imitations of masculinity but whose pedantic, overconfident, authoritarian style reassures these insecure white men that someone is still on their side.

2. Modernity is increasingly complex, confusing, overwhelming, and scary. Rapid change — both cultural and technological — is increasingly alienating many people who feel excluded or left behind by those changes. Authoritarian leaders can appeal to this disorientation, confusion, and anxiety, and create scapegoats that have nothing to do with the actual causes, but are very useful in ginning up votes. These leaders also tend to appeal to nationalism, which helps restore pride.

3. There is increasing exploitation, abuse, and enslavement of the have-nots by the haves everywhere around the globe. This makes people want to rebel, to regain agency and self-respect, and some authoritarian candidates have a knack for hoodwinking people into believing that they (those candidates) have all of the answers to restore freedom and dignity to folks who feel beaten down. In reality, however, authoritarians usually oppose the real remedy democracy itself — and good government and civil society — making these the “bogeyman” that have caused all the problems for the have-nots. In reality, it is big business, crony capitalism, and capture of elections and government itself by wealthy owner-shareholders that have created this imbalance and oppression. But authoritarian leaders are usually in bed with those same plutocrats, and not at all interested in addressing the underlying problems. So in fact the problems just get worse.

4. The masses have been numbed into complacency, indifference, and apathy by a moderate level of wealth, entertainment, constant calls to action (from politicians, advertising, etc.), poor diets, lots of propaganda and disinformation, a decline in IQ and education, and other things that distract or impede them from taking appropriate action or even clearly understanding the problem. I see this as a modern version of “the spectacle,” with many other characteristics and contributing factors that you can read about here:

L7 The Spectacle

My 2 cents.

I think that there are a few principles that might aspire to “the most important principles in political philosophy,” and I’ve listed them below. I don’t, however, think there is any single political philosophy that can claim primacy as “the most important in history.”

Some principles that became quite influential, if not universal, throughout history around the globe:

1. That rulers — or anyone with disproportionate concentrations power — should be just and good to those they rule or control…and, if they aren’t, that they should be usurped or replaced in some fashion (democracy, violent revolution, communism, anarchism, etc. all sprang from this central idea)

2. That all human beings share the same fundamental rights (under the law, in political representation, economically, socially, etc.)

3. That “civil society” is not only predicated on the previous two principles, but that it exists to benefit everyone in society (i.e. provide safety and security under the rule of law, material opportunity, freedom, and even the pursuit of happiness…)

4. That religion and governance do not mix well…but scientific evidence and reasoning bolsters sound governance

5. That the civic responsibility for all-of-the-above falls upon everyone equally — that everyone is individually and collectively accountable for the fulfillment and defense of these principles.

Sadly, although these principles have led to some of the grandest, most prosperous, most free, and most advanced societies on Earth, they seemingly are being forgotten to an astonishing and rapid degree. Like spoiled children, modern citizens do not seem to understand or appreciate what they have…until it starts to be taken away.

My 2 cents.

This has been a central focus of my own philosophical reading, research, musings, and writing for many decades. It took me a while to arrive at these conclusions…but what follows is where I have landed for the moment.

I should first give a nod to the lineage of the dialectical epistemic mode in Western philosophy, where we see the primary evolution from Plato and Aristotle up through Hegel. I also think Calvinist multiperspectivalism adds to this tradition, with a synthesis of three perspectives. Beginning with Gebser we begin to see a new definition of “multiperspectival” among integral philosophers, and really this is the beginning of what I would call “high-level dialectical thinking.” In this form of analysis, many perspectives contribute to an additive synthesis.

Finally, there is a parallel lineage in Eastern philosophy and mysticism as well, which leads to subtly different epistemic assumptions: that some understanding can’t be logically derived, but only “known” in a more felt or spiritual sense, described with terms like “gnosis,” “kensho,” and “bodhi.” This illuminating awareness also encompasses multiple perspectives in its interpenetrating understanding — it can integrate without negation just as Western dialectical and integral methods attempt to do.

This is not to say that Western philosophy doesn’t brush up against sympathetic ideas — it does. I think arriving at Aristotle’s moderation, or Fichte’s intellectual intuition, or Heinlein’s “grok” all seem to require a similar flavor non-analytical insight.

All of this led me to a very particular conclusion: there are many ways of knowing, and many ways of integrating that knowledge, so that a true “synthesis” of understanding that encompasses all experiences, insights, and perspectives requires a different framing than what either Western or Eastern philosophical traditions had to offer alone.

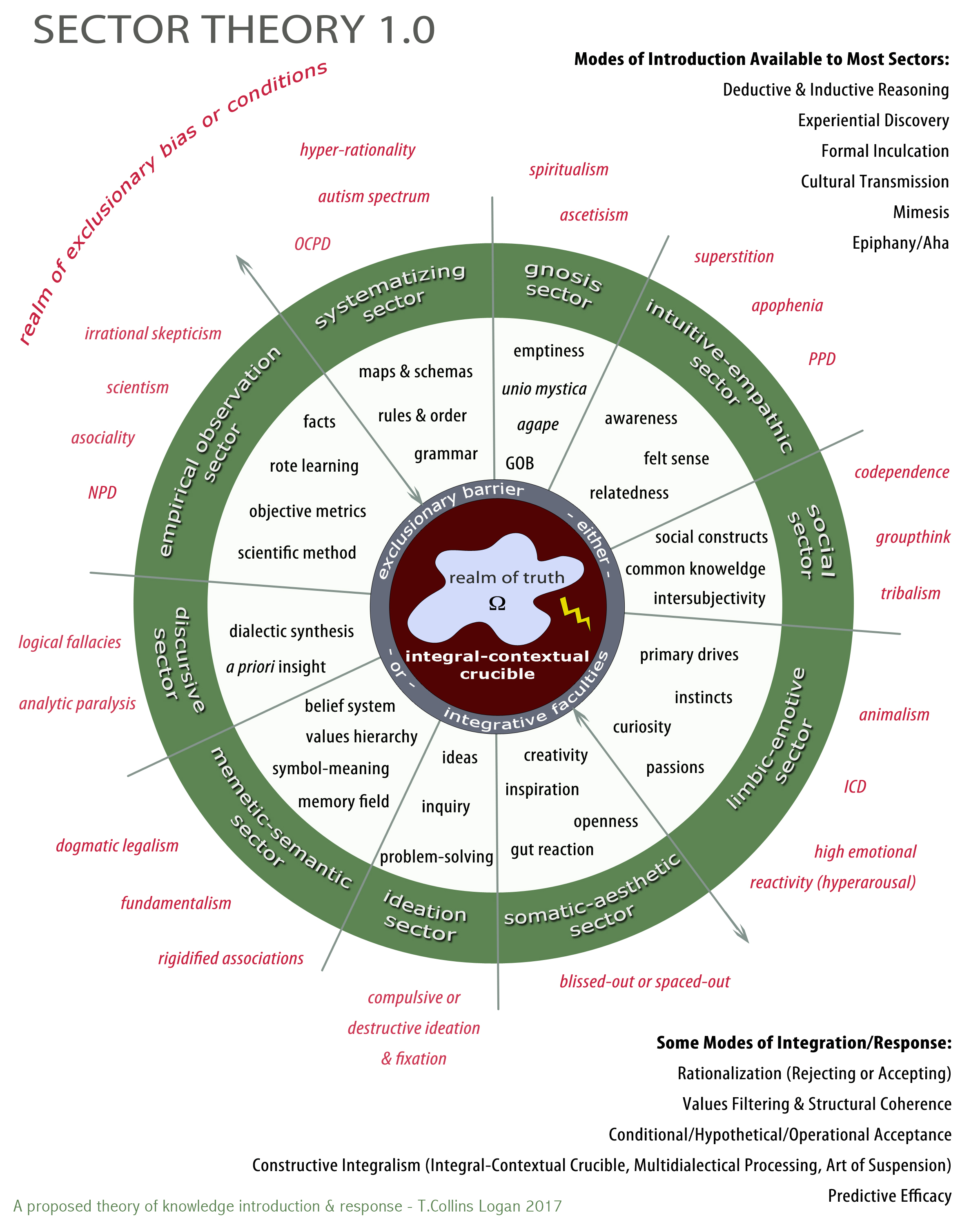

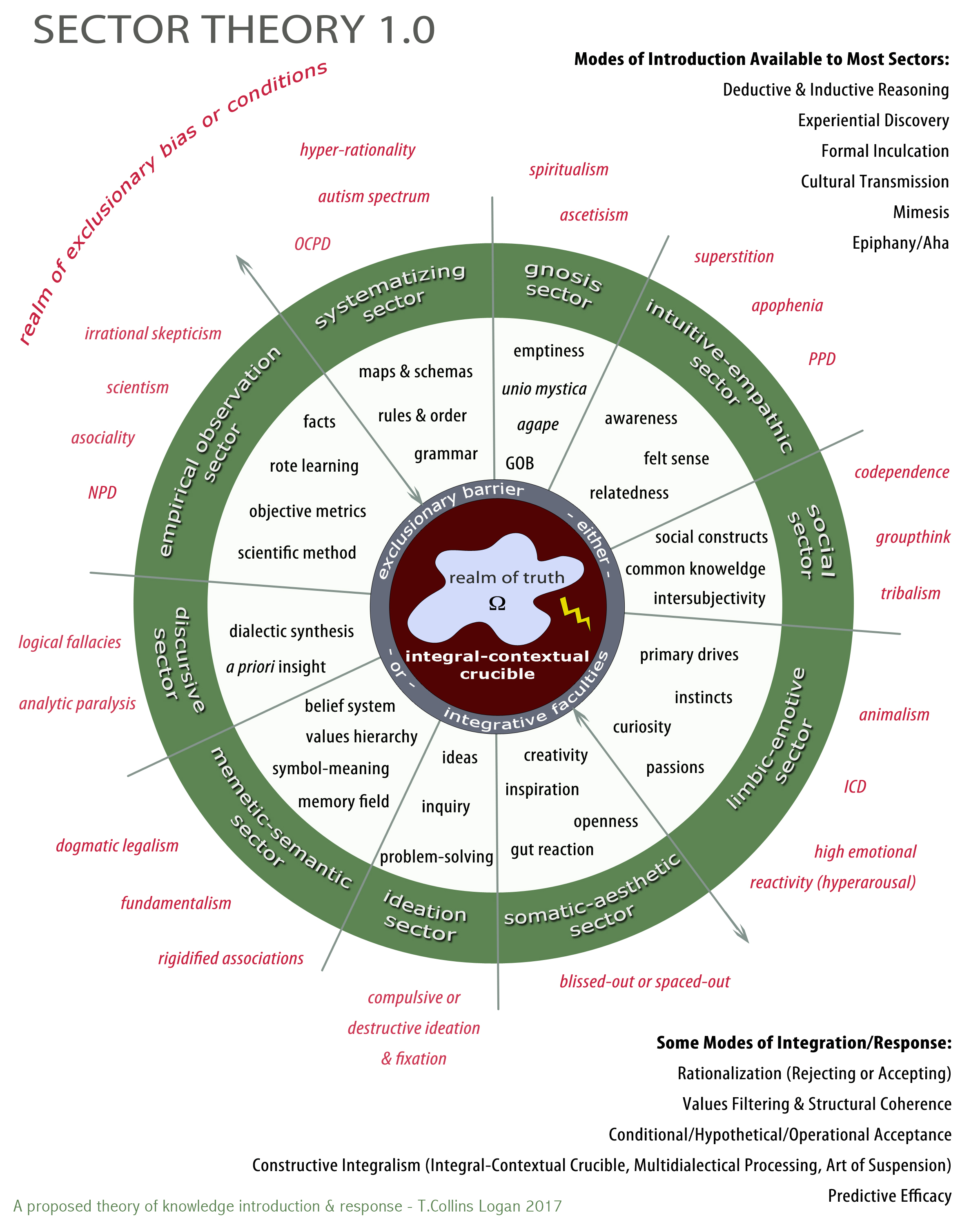

This is how I arrived at

Sector Theory, an overview of which is represented in the graphic below. This epistimic framework is still under development (I’m currently working slowly on version 2.0), but you can read a summary of version 1.0 here:

https://www.academia.edu/32747714/Sector_Theory_1_0_Todds_Take_on_Epistemology

Sector Theory is how I would represent “high-level dialectical thinking.” The term I like to use for the fundamental process is “multidialectical synthesis.” What makes Sector Theory unique, however, are the definitions of the sectors themselves.

These sectors aren’t always equal contributors — it requires discernment and wisdom to know which combination of sectors should have primacy in a given situation or realm of understanding — but Sector Theory asserts that all should be considered and weighed carefully together for the most complete understanding possible.

My 2 cents.

I think it is a lofty ideal, but that it has never really existed in the U.S. “Principled conservatives” claim to base their ideology on actual sources like the Constitution, or the intent of the Founding Fathers expressed in the Federalist Papers and other essays and letters of the period, or the writings of Adam Smith and John Locke, or the Judeo-Christian ethics of the Bible, or other similarly vaunted authorities of the past.

The problem, of course, is that most of this framing has been achieved through radical reinterpretations of those sources by more recent thinkers, and the “core principles” have become severely distorted so that the new lens of conservative values teeters on a cherry-picked mountain of half-truths. This has been going on for a long time in the U.S. and elsewhere, as conservative religious and political figures have sought to harness authoritative source material to justify their own power, influence, wealth, and gender and racial superiority. Citing such authorities in conservative propaganda makes it a lot easier to persuade a conservative-leaning rank-and-file to vote a certain way and dutifully conform to the party line.

I suppose some examples would be helpful here, and there are many. It’s just that you have to really study that source material carefully to understand just how distorted conservative reinterpretations have become. Take women’s rights as one example. Established culture always trumps religion, and the Europeans conformed what was actually a radically feminist Christianity to their own misogynistic cultural tendencies, and that misogynistic strain of Christianity then migrated to the New World. If we spend any time at all studying the acts of Jesus and the writings of the Apostle Paul, we quickly realize that they both promoted a woman’s spiritual authority and position in the Church as being equal to a man’s, and frequently deferred to female leaders and influencers in critical situations. The words and deeds of the New Testament are radically feminist in this sense. That is…except for two (and only two) verses in the epistles (i.e. the letters at the end of the NT) that denigrate women and put them in subjection to men, and which conservatives have often liked to cite to justify ongoing oppression of women. However, nearly all — and certainly all of the most credible — modern Christian scholars recognize that these epistles are rife with interpolated verses…that is, with verses that were written centuries later and inserted into those texts…and due to their style and content these epistles were very likely written or rewritten at a much later time than the rest of the New Testament. Again though, we’re talking about two verses that contrast the majority of other NT writings that quite markedly liberate women from oppression and inequality.

So, as I say, this “cherry-picking” of conservative authorities has been going on for a long time. The same is true of Adam Smith, who promoted “good government” and its control over and taxation of commerce so that workers and the poor would be protected from the abuses of big business. Hmmm….why is it we never hear conservatives quote Adam Smith’s discussion of good government? Because it doesn’t conform to their narrative about unfettered free enterprise being synonymous with liberty and American patriotism. And of course similar distortions have arisen around how the U.S. Constitution is interpreted, which clearly states government is to provide for the common welfare of the United States, enshrines enduring socialist institutions like the Postal Service, and so on. Equally distressing, conservative distortions go so far as to invent — in what is a stark contrast to “principled” originalist or textualist interpretations of the Constitution — self-serving ideas about what a particular passage means. For nearly 200 years the phrase “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms” was understood to relate to the “well regulated Militia” referenced in the same Amendment — even among conservative SCOTUS Justices. But, thanks to modern conservatives and the revisionist judicial activism of Antonin Scalia in his DC v Heller ruling, Amendment II now somehow refers to personal self-defense…!

Essentially, then, conservatives have traditionally begun with a self-serving objective — usually having to do with creating or maintaining white male pseudo-Christian privilege and wealth in society — and then carefully gleaning selective passages from authoritative sources from the past to support those self-serving objectives. These distorted justifications then become their “conservative principles.” Ironically, most of these self-protective and highly destructive conservative ideological habits can be quickly countered with other selective references from those very same sources — for example, both Jesus Christ and Adam Smith frequently warned of the dangers of greed and lust for power, the toxicity of lording it over others, and so on.

But in my experience very few “principled conservatives” spend much time really understanding or even reading those original sources. Some do, and their views are much more nuanced (but not at all popular among other conservatives!). Instead, the average “principled conservative” relies on the reinterpretations of much later thinkers and influencers who became conservative authorities in their own right — Hayek and Friedman, Gingrich and Buchanon, Scalia and Rehnquist, Graham and Falwell, the American Enterprise Institute and Heritage Foundation, Breitbart and Blaze, Buckley and Limbaugh, and so on. So with each passing generation, the abstraction from first principles becomes more and more elaborate and rationalizing…until we end up with a fascist, racist ignoramus embodying the very worst of human nature, and 70 million GOP voters supporting it as their “conservative” choice for POTUS.

Essentially, then, the principles of “principled conservatives” have become very far removed from the ideals of the original thinkers that supposedly inform them, and are reduced and upended into the very things those authorities warned against and attempted to countervail:

“All for ourselves, and nothing for other people, seems, in every age of the world, to have been the vile maxim of the masters of mankind.” — Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations

“You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great ones exercise authority over them. It shall not be so among you. But whoever would be great among you must be your servant…” — Jesus Christ (Matt 20:25–26)

“For rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad. Would you have no fear of the one who is in authority? Then do what is good, and you will receive his approval, for he is God's servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for he does not bear the sword in vain. For he is the servant of God, an avenger who carries out God's wrath on the wrongdoer. Therefore one must be in subjection, not only to avoid God's wrath but also for the sake of conscience. For because of this you also pay taxes, for the authorities are ministers of God, attending to this very thing. Pay to all what is owed to them: taxes to whom taxes are owed, revenue to whom revenue is owed, respect to whom respect is owed, honor to whom honor is owed” — Apostle Paul (Rom 13:3–7)

“We should replace the ragbag of specific welfare programs with a single comprehensive program of income supplements in cash — a negative income tax. It would provide an assured minimum to all persons in need, regardless of the reasons for their need.” — Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom

“I think by far the most important bill in our whole code is that for the diffusion of knowledge among the people. No other sure foundation can be devised, for the preservation of freedom and happiness...Preach, my dear Sir, a crusade against ignorance; establish & improve the law for educating the common people. Let our countrymen know that the people alone can protect us against these evils [tyranny, oppression, etc.] and that the tax which will be paid for this purpose is not more than the thousandth part of what will be paid to kings, priests and nobles who will rise up among us if we leave the people in ignorance." — Thomas Jefferson, Letter to George Wythe, 1786

There are so many more examples…!

My 2 cents.

The challenge as I see it is the weaponization of malicious deception through mass and social media. Take propaganda and disinformation. Before record broadcasts, mass media, and the Internet, this was limited to influencing those within hearing distance of a live speaker — or to those willing to read and absorb someone’s writing — and thus only seemed to propagate slowly over months and years. Mass movements were sparked by radical and revolutionary thought, to be sure, but the time these took to gain any substantive momentum in society afforded a modicum of wisdom, measured consideration, thoughtful discourse, and common sense to be injected into that process…well, at least most of the time. Humans have always been susceptible to groupthink and the lemming effect. But before the modern information revolution, the ability to hoodwink large numbers of people took some very committed effort and time.

Nowadays, however, disinformation disseminates in hours or days, capturing millions of uncritical and gullible minds so that substantive shifts in attitudes and behaviors can have a widespread — and often dominant — impact on communities and societies. I call this the superagency effect, and it is similar to other ways that technology allows us to project and amplify person or collective will in unprecedented ways…often facilitating great harm on an ever-growing scale.

So I think this change in the potential consequences of malicious deception — the amplification of harm, if you will — should inform our definitions of free speech, and the collectively agreed-upon ways we decide to manage free speech. I think this is part of what the Fairness Doctrine in the U.S. was intended to address: the advent of news media broadcasting to every home in America invited some sort of oversight to ensure what was being communicated in an ever-more-centrally coordinated way, by relatively few authoritative or trusted figures, offered equal time to multiple perspectives…and encouraged some of those perspectives to be controversial. Since the original Fairness Doctrine only applied to broadcast licenses, it of course would not have done much to curtail the explosion of propaganda and conspiracy outlets on cable and the Internet unless updated to address those new media (and there was, actually, a failed attempt to do this), but the point is that the concern about the ubiquity of these forms of persuasive communication has always been pretty obvious.

And of course this concern doesn’t only apply to ideological propaganda. It also applies to advertising, which has successfully convinced millions to buy things they don’t need, or become addicted or dependent for many years, or injure their health and well-being with caustic consumables. Again, all because of the power and reach of mass media.

So the vaunted ideal of free speech has to be understood in this broader context. The speed and destructive power of malicious deception in the current era cannot be understated. It has undermined legitimately elected governments, endangered individual and collective human health, propagated irrational fears and hatred that have lead to human tragedy and death, and wreaked havoc on the ecology of planet Earth — all with astonishing swiftness and scope.

Therefore, some sort of collectively agreed-upon mechanism — and ideally one that is implemented and managed by an informed democratic process — should be put in place to ensure some standard of truthfulness and fact-checking, representation of diverse and controversial perspectives, and diffusing or disabling of disinformation and malicious deception. The key, again, will be in the quality and fairness of the “regulatory” process itself — aiming for something more democratic and not autocratic.

My 2 cents.

My take, as someone who has read both Sartre in French and Hegel in German, is that learning the language alone is certainly helpful, but does not guarantee understanding. As others here have said, each philosopher has their own distinct language — some even invented their own vocabulary for ideas they otherwise found impossible to communicate. There is also the issue of language period — the phrasing, syntax, vocabulary, and cultural references of a specific time can add to the potential confusion.

So my recommendation would be to both learn German, and study the original text alongside two or three well-respected translations in your native tongue. This approach has afforded me many interesting surprises and insights. On the one hand, you will see how different translators grapple with difficult passages and you can then perhaps gain addition insight from that. On the other, you may very well discover that none of the translations really captures the nuance of the original language as you read it. These are exciting learning experiences.

For me, reading Hegel in German was very difficult, and reading Sartre in French was relatively easy — and this was despite my German being much more advanced than my French! Nevertheless, I don’t think I would have arrived at the understanding I have now of each thinker; still humbly incomplete, but more clear-eyed and balanced, I think, than what some professors and commentators I’ve encountered over the years have attempted to convey.

In other words…I would recommend digging into philosophy with a “multiperspectival” or “integral” discipline, where you weigh several vectors of investigation against each other, and synthesize your own conclusions. I would describe this as a multidialectical approach. At the same time, it should be warned, this method will not help you pass exams or be more popular in a given philosophy club; in fact it may hinder you. All-too-frequently, you may be scoffed at by someone who insists their professor’s views on a given philosopher are more sound than your speculation. It won’t matter that you explain a given position, just that you are somehow impugning a vaunted authority on the matter. In academia, conformance of thinking is often much more important (for decent grades, at least) than thinking deeply or critically.

Okay…probably offered more than the OP wanted to know. But there it is.

My 2 cents.

Here is the underlying problem as I see it: Blind, uncritical, or unthinking adherence to any “ism” is always misguided. There are good ideas — great ideas, even — available in every camp, but when loyalty and lockstep adherence to a given tribal membership or belief system becomes more important than discerning which ideas are good and which are bad, or even than having an intellectually honest dialogue with others with different perspectives and strategies, then that “ism” is just a restrictive and destructive straight jacket.

Right now, there is some of this behavior on both the Left and the Right. However, lockstep conformance and uncritical groupthink have lately become much more common on the conservative end of the spectrum. And this is the real problem, more than anything else IMO. Add to this that many of the ideas being championed by conservatives are informed by non-factual assumptions (climate change is a hoax; face masks won’t help control COVID; free markets and the profit motive always solve complex problems; the U.S. was founded by Christians for Christians; etc.), a profound misunderstanding of causality (for example: Planned Parenthood clinics do not increase abortions rates, they actually decrease abortion rates; stopping immigration will never restore U.S. jobs; there is no widespread election fraud; and so on); affection for policies and practices that have clearly proven ineffective or outright failures (supply-side economics; war on drugs; austerity measures; nation building; structural adjustment policies; deregulation; etc.), and opposition to policies and practices that work exactly as intended (Head Start; ACA; Keynesian macroeconomics; etc.). In short: modern-day conservatives just get most things terribly wrong.

As to the “underlying principles,” well sure, there is some really good stuff to be found among the more thoughtful conservative thinkers of past eras. And there is no reason to abandon the inclusion of intellectually honest conservatives in modern discourse. It’s just…there don’t seem to be many intellectually honest ones around right now, and a lot more ideas on the progressive side that are guided by scientific evidence and practices proven in the real world.

My 2 cents.