Thanks for the great question. IMO the solution is to veer away from

vertical forms of both individualism and collectivism, and toward

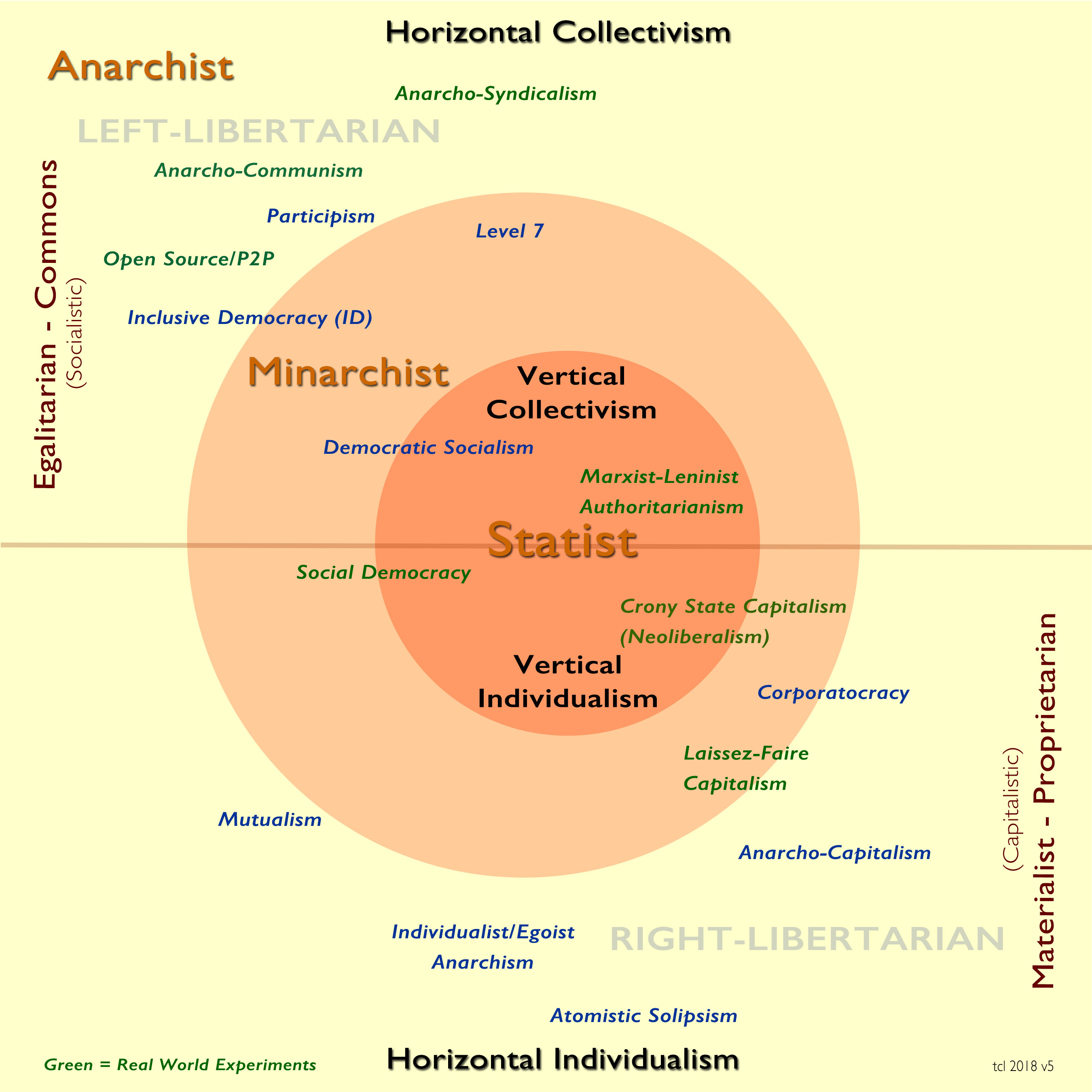

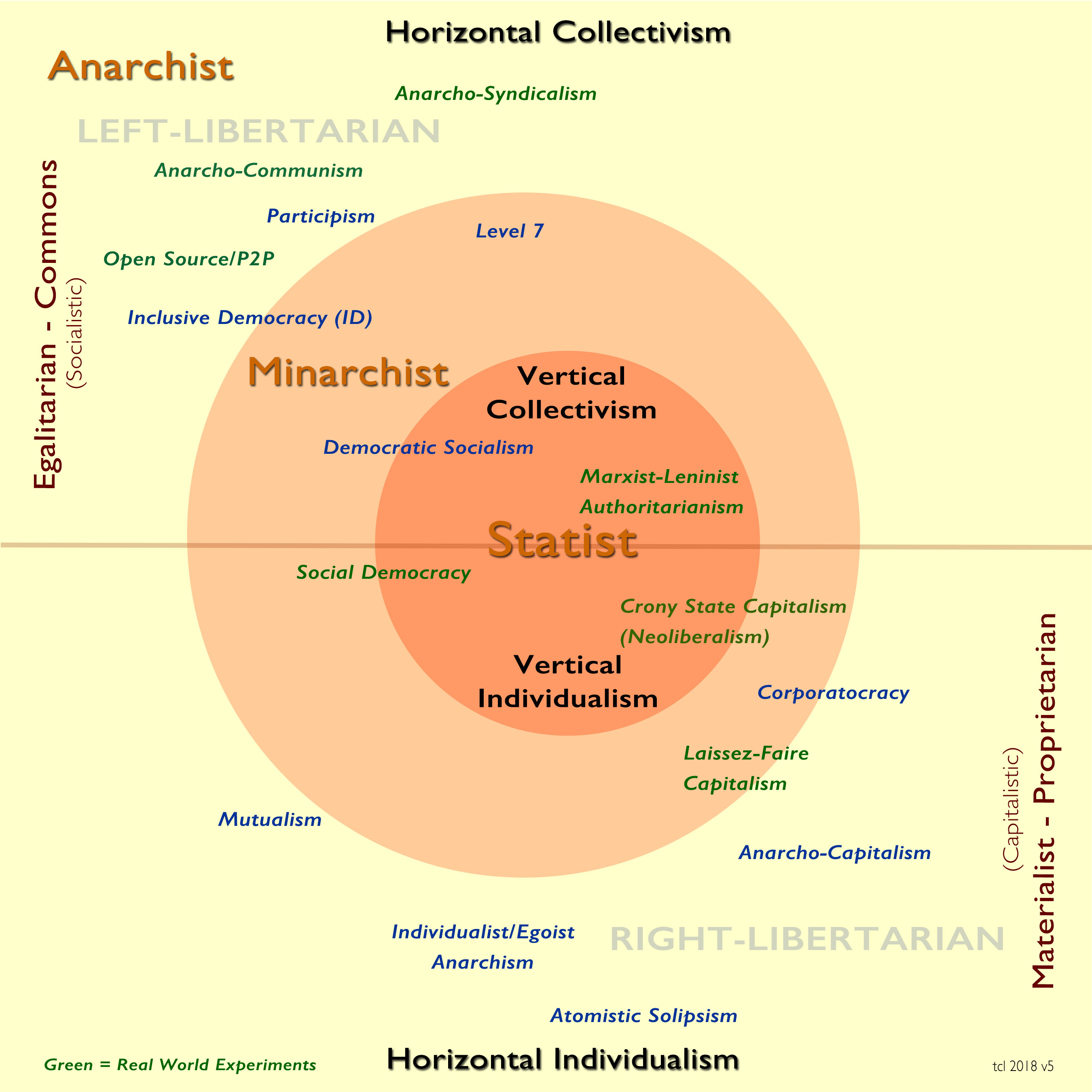

horizontal forms that incorporate the best of both. Here is a chart that helps appreciate this difference:

As you can see, an additional consideration (in terms of political economy) is the “materialist-proprietarian” vs. “egalitarian-commons” axis. I tend to aim for the egalitarian-commons side of this spectrum, because I believe it harmonizes much more readily with both democracy and compassionate consideration of other human beings.

My 2 cents.

Thanks for the question.

What gives ownership of property its legitimacy? Only the fabricated architecture of the rule of law as created from whole cloth by human beings, usually to facilitate material security in isolation from society…and of course to facilitate trade. But extending personal sovereignty over one’s own mind and body into property — as in the longstanding tradition of Locke’s theory of labor appropriation — is a convenient, self-justifying fiction that borders on ridiculous. It’s little different than a dog believing it “owns” a patch of grass that it has peed upon, or a bird “owning” a tree where it has built its nest, or a hunter “owning” a wild animal they caught in a snare…these are all just variations of a King of the Mountain children’s game. There is no “natural law” that extends “mind and body” into property of any kind…only made-up belief constructed to justify appropriation, defense of property, and commerce.

As I discuss at length in these essays:

Integral Liberty and

Property As Violence,

property ownership is actually a non-rational impulse that interferes mightily with liberty, is predicated on ego-centrism and atomistic individualism, and is incompatible with the Non-Aggression Principle (NAP). It is, essentially, a very immature and irrational way of interacting with our environment (unless you are a dog, a bird, a bear, etc.) that ends up reflexively depriving everyone else of their liberties. In this sense, ownership is primarily an antisocial behavior, regularly violating the non-aggression principle. Someday — hopefully in the not-too-distant future for humanity’s sake — we will begin to shift back into the more sane, rational and prosocial mode of possessing things temporarily for their utility, enjoyment or resource contribution, but without the childish need to “own” them during this temporary possession. We’re getting there…slowly…with concepts like Open Source. But we have a long way to go.

My 2 cents.

I would say Pinker’s observations are explainable by the rise of civil society and the stabilization of its institutions over time. Ethics have not really evolved all that much during recorded history — not in the broadest moral sensibilities and contracts at least. Sure, there is variation across different cultures…but really no more variation over the grand arc of history than is evidenced in current cultural differences. The ancient Greeks had an advanced civil society with many of the benefits of modern democracies, and we have State-sanctioned genocide today just as we have had for the past two thousand years. The apparent reduction (per capita) of violence, war, etc. that Pinker explores is really not a consequence of ethics changing, IMO, but of civic institutions relieving many of the pressures that produce unethical behaviors. We are shaped by our environments to the extent that our natural propensities will be amplified by either a sense of safety, social support and relative affluence, or by insecurity, fear, deprivation and violence. We have always had (and probably always will have) the capacity to behave like animals, or like saints, but our experiences will encourage one cluster of habits over the other. So the greater the civic stability, the greater the potential for widespread prosocial behaviors.

Just my 2 cents.

Thank you for the question Rachel. Some possibilities:

1) Because capitalism has been failing most people for a really long time.

2) Because nearly ALL of the social safety nets, worker protections, consumer protections and other benefits for the non-wealthy in the U.S. are a consequence of policies championed by socialists or inspired by socialism. Child labor laws, worker unions, socialized medicine (Medicare) and so on are all a consequence of socialistic values and ideology.

3) Because the lies and deceptions of neoliberal propaganda (i.e. “trickle-down economics always works”, “all forms of socialism have always failed,” etc.) are becoming more and more obvious, and people just aren’t being deceived as easily.

4) Because people see how socialized systems and socialistic values in other countries have been quite successful.

Because, despite concerted efforts from neoiberals and right-libertarians to deny or distort the reality, a “

mixed economy” like that of the U.S. is a mixture of socialism and capitalism…and has been for a very long time.

In other words, people are calling for a more socialistic society because they are waking up from the spectacle that has kept them from seeing how rational, compassionate and commonsensical such a society really is.

My 2 cents.

Ah. Good one.

I think the answer to this question depends on the level of moral maturity involved. An immature person will tend to disregard the rights of others unless someone (or some thing) is present to enforce or defend those rights. A moral grown-up, on the other hand, will recognize the importance of such rights even if there is no one and no thing present to enforce or defend those rights. This is true of most ethics. The morally mature person may choose to work hard whether their boss or coworkers are watching or not, because they believe it is the right thing to do; whereas the morally immature person may only work hard to impress upon those watching them that they are indeed “a hard worker,” or to reap some sort of advantage or reward. Really what defines being an adult has a lot to do with this willing acceptance of societal expectations without expectation of reward (i.e. simply because it is prosocial), while refining one’s own conscience to act in the spirit of those expectations on the other. A child, in contrast, might only follow the letter-of-the-law while someone is watching, and be excited and thrilled to deviate from societal expectations if nobody is looking.

These contrasting levels of moral maturity quickly become evident in contexts like driving a car: the mature person “drives carefully and responsibly” out of compassion for their fellow human beings, polite consideration that reflects prosocial intentions, and acknowledgement that the rule of law is necessary on public roads to prevent utter chaos and death; the immature person thinks the rules don’t apply to them, that other people’s safety doesn’t really matter, and that their own self-gratification and arbitrary impulses should guide their driving habits. In such a situation, the moral adult has little fear of police presence on a highway, whereas the moral child tends to be a bit more angry and fearful in the midst of their egocentric rebellion. So we might say that, for the moral toddler at least, a right may not exist if their is no one to defend it.

Thanks for the question.

(see:

https://www.quora.com/link/A-simple-chart-shows-what-some-economists-consider-to-be-the-most-striking-development-in-40-years-of-the-US-economy)

LOL. This question really tickled me, so thanks for the question.

It’s not the correlation I find interesting, but the causal phrasing. “Has the rise of the gig economy…” (as if it were some spontaneous thing) “…contributed to great wealth disparity…?” Both are the consequence of precisely the same downward pressures on wages, employment security, and economic mobility…and the same upward pressures on wealth concentration. These two forces have been in play for quite a while now (over fifty years), and certain consequences (like the weakening of unions, loss of entire sectors of blue collar jobs, the financialization and automation of the economy, and so on) are inevitable. To understand the underlying mechanisms, one has to reframe the discussion around growth-dependent capitalism itself, and its constant shifting reach for cheap labor and cheap resources in order to sustain that growth, while still enlarging the profits of owner-shareholders as an “acceptable” return. The gig economy had to happen in this context — just as corporations had to start shifting away from full-time employment to contract labor. Both wealth disparity and job insecurity are absolutely deliberate in this context. Until we rethink these fundamental expectations of capitalism, it’s only going to amplify such trends.

My 2 cents.

No it will not…and never has. After ALL Republican historical tax cuts for the wealthy aimed to “stimulate the economy,” low-end wages remained stagnant, the number of folks living in poverty remained the same or increased, and income inequality consistently increased. In addition, the central claim to fame for supply-siders is that tax cuts stimulate economic growth…but at the macro level this has been extremely hit-and-miss (see links below).

But, more importantly, there has not been any substantive or sustained “trickle-down” to the poor as a consequence of tax cuts for the rich, ever. All other statistics are largely irrelevant in this context, because the sole measure of whether trickle down and other supply-side fantasies (i.e. the Laffer curve is laughable) actually work is

whether poor people get any less poor. Well, they don’t. So it’s just B.S. to talk about economic indicators at a macro level that benefit the wealthy, when what happens to the poor (in terms of real wages, numbers of folks in poverty, etc.) is so clearly neutral or negative. Here are some decent articles that cover this topic (you will need to follow links and refs in them to burrow down to the actual data):

How Much Do Tax Cuts Really Matter? (Summary of Census Bureau reports on income and poverty across multiple U.S. administrations.)

Tax Cuts Won’t Make America Great Again

Trickle-Down Tax Cuts Don’t Create Jobs - Center for American Progress

How past income tax rate cuts on the wealthy affected the economy

Tax Cuts: Myths and Realities

Now of course if you do a Google search on this topic you will find endless articles from the Heritage Foundation, CATO Institute, American Enterprise Institute and other neoliberal think tanks that prop up supply-side fantasies with cherry-picked statistics. It’s really shameful…but this deluge of propaganda serves these neoliberal institutions well: they have forever been the champions of corporate plutocrats, after all.

Thanks for the question Jeff.

The pros are the real possibility of intuiting nuanced unities among all spiritual traditions, which in turn lead to a deeper appreciation of both spiritual substrata (ground of being, gnosis, sophia, etc.), and the metathemes that have informed humanity’s spiritual and moral journeys — and indeed influenced cultural developments — for millenia. The cons are, as Thomas Merton succinctly surmised, that undisciplined Perrenialism can become “loose and irresponsible syncretism which, on the basis of purely superficial resemblances and without serious study of qualitative differences, proceeds to identify all religions and all religious experiences with one another….”

My 2 cents.

Thanks for the question Deiter. Please prepare yourself for a self-indulgent rant on my part.

A lot of folks who allude to Surowiecki’s “wisdom of the crowds” do not realize this refers to a disorganized, non-self-aware, diffused, uncoordinated and essentially arbitrary intersection of public intuitions and insights. Anything more organized and self-aware, on the other hand, rapidly develops one or more weaknesses related to conformative groupthink. We hear regular complaints about bureaucracy, inefficiency, turf wars and serfdoms, quid pro quo dealings, corruption, the lemming effect, gridlock, complacency, and a host of other issues that plague organizations larger than a few individuals. Essentially, humans suck at “big,” as it too often tends towards unskillful, inept, or just plain stupid.

Now I won’t go into why this seems to be a recurring problem — it could be something as simple as the combination of the Dunbar limit, the inherent paralyzing effect of rigid hierarchies, a genetically programmed propensity toward tribalism, and an institutional version of the Dunning-Kruger effect. Again…not the focus of this answer. What I do want to elaborate on is the necessity of outliers in any such institutional ecosystems. Without outliers, the quicksand of organizational inertia will always destroy that organization from the inside out. Not in any exciting sort of implosion, but through a slow, insidious rot. Outliers provide the necessary injection of challenging the hierarchy, outsider insights, and “creative destruction” that allows revisions and evolutions to occur in an otherwise frozen soup of conformance.

A lot of folks have intuited aspects of this principle and its importance in society. Colin Wilson, Dostoyevsky, Sartre, Gebser and many others have explored the significance of outsider experience, thought, art and contributions to society. And this is not a new idea…perhaps you will recall Jesus saying “Truly, I say to you, no prophet is acceptable in his hometown.” So the idea that the outlier, outsider, or outcast in this same sense must bear the burden of isolation and rejection in order to rejuvenate society — and indeed human civilization — from the outside has persisted throughout millennia.

As another take, in-groups like to scapegoat outcasts, so outcasts perform an important function there as well — diffusing tension, exciting group unity, voicing taboo sentiments, diluting hierarchical control and power, etc. Consider the “class clown” or the King’s Fool. There is, I believe, something inherently necessary about the outcast — something essential to the thriving of society itself. Certainly to the arts. Reframing common experiences and the status quo as absurd parodies of themselves is perhaps what comedians, social critics and theatre have provided since the beginning of history.

So society has outcasts to preserve itself. Without them, it would disintegrate.

My 2 cents.

Addiction is, IMO, woefully misunderstood by both modern science and mainstream folklore. Of the ten answers so far in this thread, all of them miss the mark. Biochemistry can help us understand mechanisms of physiological response, but not the causality of addiction itself. Not by a long shot.

In Integral Lifework, most addiction is the consequence what I call “substitution nourishment.” This is when some dimension of our being isn’t being nurtured or nourished, and we attempt to compensate for that deficit in other areas. The areas can be completely unrelated — and there are thirteen I have identified so far, which makes for some odd remedies. For example, one of my clients with OCD who was addicted to caffeine and certain sexual fetishes lost both his compulsions and his cravings when he began to create real intimacy with people — both romantically and in friendships. The caffeine and fetishes were no longer required to “offset” his loneliness, isolation and intimacy starvation. And I’ve seen a similar pattern repeated many time in many other clients.

Is there good data to back up this assertion? Not really. The Rat Park study points in a helpful direction, but the study was poorly constructed IMO. But this is the direction we need to look in in order to understand addiction.

Now I did say “most” addiction, and that is because some addictions are more structural in nature, and there is a growing understanding around genetic markers for certain sensitivities/vulnerabilities. That is a separate topic. But even in such “structural” instances, if all thirteen dimensions of our being are attended to and in harmony with each other, then even those vulnerabilities have less pull on a whole and healthy human being.

My 2 cents.

Thanks for the question. Well, in terms of “sayings,” there are many — things that were said by my friends when I was young, things I read in books over the years, things a teacher or mentor shared, things I heard at rallies and speeches, things a poet or musician crafted…so many. I think it is the totality of these influential pronouncements over time that led me to appreciate the power of language itself — to capture sentiment, to peel back the onion of insight, to generate sudden “ahas,” and do forth. And that appreciation has certainly stuck with me. It is a large part of what shaped my own desire to write essays and books, create music and songs, and for a few years to act on stage. Even in the midst of a casual conversation, I am fascinated with capturing the essence of an idea, experience or emotion in words…obsessed even. So the recognition of the beauty and power of language certainly persists, even into the briefest exchanges. And of course it is very likely why I participate in Quora.

In terms of influential events, well, those are equally plentiful, and what I have often written about — including how they have shaped my self-concept and ways of being. My book Memory : Self is focused mainly on this interplay.

But is there just one of each that I could point to as more profoundly influential than all the others? I suspect it would be different pairing on different days, depending on my mood — and certainly the emphasis has changed at different times in my life — so I’ll just share what bubbles up right now:

1) When I was twelve or thirteen years old, my dad, a clinical psychologist, explained the bell curve of human intelligence to me. He showed how most people hover within a few points of the mean IQ of 100. I was astonished. 100? Really? And only a slim percentage ranged 120 or above? I was stunned. How was that possible?! At that moment I began to realize one reason why so many really, really bad decisions get made both collectively and individually in human society: human being just aren’t that bright, on-the-whole. That’s not to say we can’t learn how to make wise decisions, or have profound insights into our condition, or even come up with some very clever ideas about how to solve complex problems. The history of human civilization is proof that, at least sometimes, humans can get things right. However, that history — including the very recent history of the past few years — also evidences that people can be really profound idiots. So having a way to frame this, to understand it in a statistical sense, has been very helpful. And of course that same bell curve applies to all sorts of other metrics, too…So, thanks Dad!

2) I think my own (albeit gradual and reluctant) spiritual awakening has informed my life in persisting and transformative ways.

3) Anyone who has had an abusive childhood knows that negative self-talk and downward emotional spirals can persist even with lots of therapy, lots of positive accomplishments, and lots of healthy relationships well into adult life. At age 52 I am still dealing with that childbhood trauma…and “managing” my own interior responses to that trauma as they are triggered (or just spontaneously well up) in the present. So…there’s that.

4) In terms of life events, what has always surprised and comforted me is the kindness I have seen in people — towards each other and towards me. I think having witnessed such kindness helps me have hope, even my darkest moments.

5) Marcus Aurelius said something that has stuck with me ever since I first read it, and it has been quite helpful in maintaining perspective: “People exist for one another. Teach them then, or bear with them.”

My 2 cents.

Thanks for the question Zahin. On the whole, I agree with Ross on nearly everything, so it would be difficult to criticize him in any substantive way. One area in which I think he could have explored and elaborated a broader foundation was in the prioritization of duties (with the aim of resolving conflicting obligations). I do think there are clear avenues of achieving this — and indeed for any situation — via meta-ethical principles (in the form of consistent values hierarchies) and synthesis (how fulfillment impulses for primary drives interact, etc.). That said, the reliance on a developed moral sense (what I refer to in my own writing as “moral maturity”), inclusive of moral intuitions and self-evident responsibilities, is ultimately a sophisticated and nuanced arbiter of such conflicts, and this is precisely what Ross seems to promote. So…I can’t really be all that critical. IMO, Ross pretty much nails it, it’s just that his exploration is incomplete.

My 2 cents.

Current excitement about a "Blue Wave" of Democratic wins in November is, I believe, woefully misplaced...for the simple reason that the wealthiest Trump supporters (inclusive of Vladamir Putin) will use every underhanded tool at their disposal to prevent or reverse any Democratic victories they can.

What these powers-that-be care most about is winning by any means possible - they will lie, cheat, steal, harass, sue, bully, intimidate and hoodwink in order to hold on to their political influence. How do we know this? Because we've seen it in many recent local and national elections:

1. Outrageous gerrymandering of congressional districts to favor Republicans.

2. Relentless disenfranchisement of Democrat voters, the poor, people of color, etc. and/or preventing them to vote on election day.

3. Aggressive attempts to hack into all levels of the election process, and the DNC, in order to disrupt free and fair elections.

4. Lockstep passage of legislation - coordinated by A.L.E.C., the State Policy Network, etc. - at the national and State levels to disrupt anything progressive: environmental protections, worker protections, unions, consumer health and safety, voting rights, etc...

5. Highly targeted deceptive manipulations on social media to persuade voters of ridiculous claims.

6. Threats, intimidation, fear-mongering and punitive policies from the White House itself to further disrupt and divide the Democratic base.

7. Relentless, carefully orchestrated smear campaigns.

8. Invented or manufactured crises that are then shamelessly blamed on Democrats.

So why should anything be different in 2018...and what other tactics can we look forward to? Court challenges for any election outcomes or lower court rulings that don't favor Republicans? Sure, with a new far-Right Supreme Court Justice on the bench, this will almost certainly be a tactic.

In the past, the only thing that has consistently countered such nefarious "win-at-all-costs" Right-wing strategies on a large scale has been

a broad upwelling of authentic populist grassroots excitement for a given candidate or agenda. This is what propelled Obama to his initial victory, what energized Bernie's rise to prominence, and what promises to undermine the centrist DNC status quo as it did with New York's election of Ocasio-Cortez.

But we should always keep in mind that whatever has worked previously to elevate the will of the people into our representative democracy will always be countered by new deceptions, new backroom dark money dealings, new astroturfing campaigns, and new methods of hoodwinking by those on the Right who want to destroy our civic institutions. Nothing on the Left can compare - in scope or the amount of money spent - to how the Koch brothers coopted the Tea Party, how the Mercer family funded Breitbart and manipulated social media through Cambridge Analytica, what Rupert Murdoch accomplished with FOX News, or how the Scaife and Bradley foundations fund fake science to weaken or reverse government regulations. Billions have been spent to deceive Americans and create "alternative narratives" that spin any and all public debate toward conservative corporate agendas. And when the Supreme Court upheld the "free speech" of corporate Super PACs funded with dark money in its

Citizens United ruling, that just opened the floodgates for more of the same masterful deception.

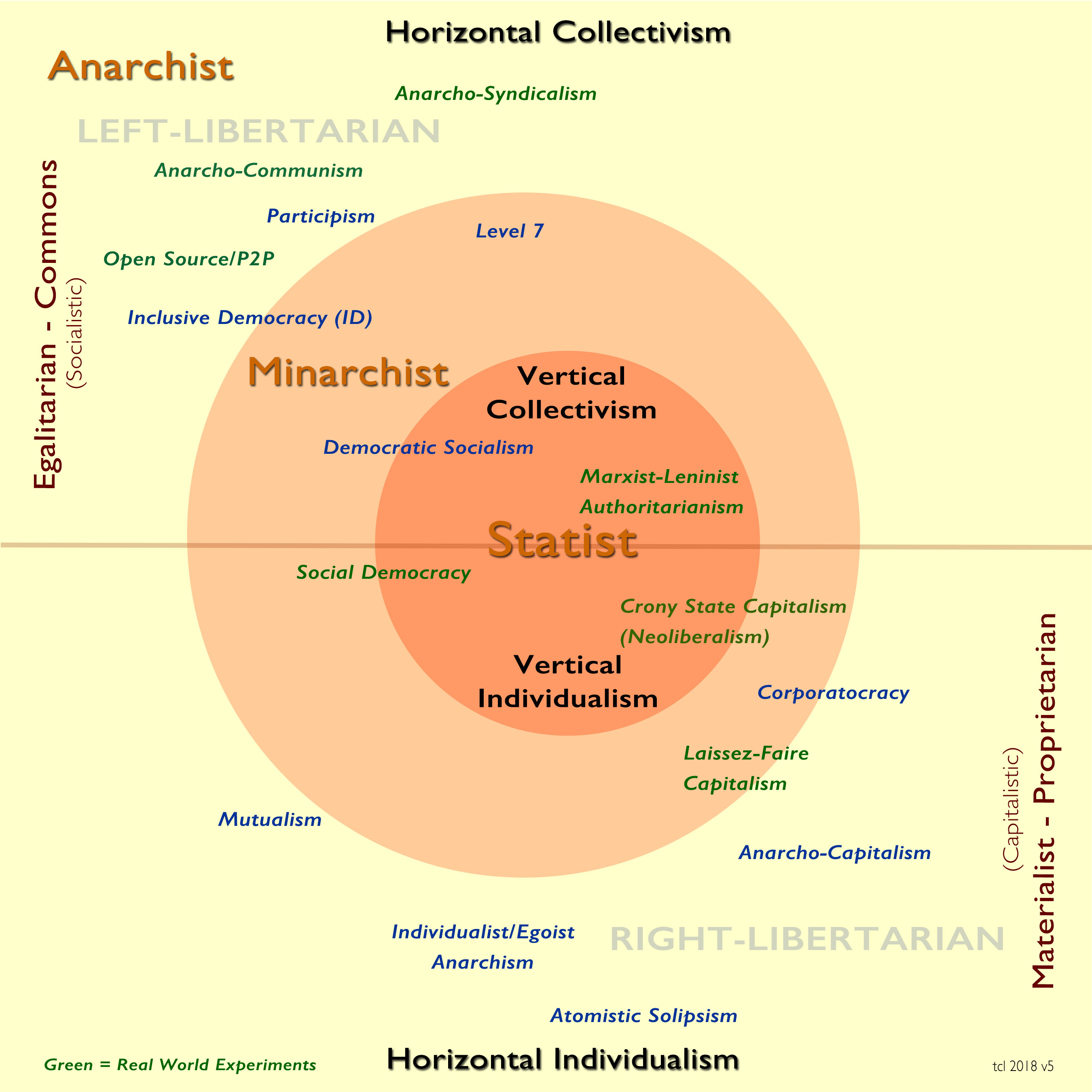

So don't count on a Blue Wave to save us from a truly deranged Infant-in-Chief and his highly toxic agenda. Civil society - and the checks and balances of power for the U.S. Republic itself - will very likely continue to be methodically demolished and undermined by neoliberal plutocrats. I wish this was mere pessimistic speculation…but I really don't believe it is. As just one example of the effectiveness of these sneaky destroyers of democracy, consider how well-organized, well-funded, and effective the "science skepticism" of the past few decades has been. Take a few minutes to absorb the graphic illustration below, and then ask yourself:

1. Do we have caps on carbon emissions, and the necessary investment in green energy technology to replace fossil fuels, to avoid further escalation of climate change?

2. Have neonicotinoid insecticides been banned so essential bee populations can be saved?

3. Has the marketing of nicotine vaping products to teenagers been stopped to prevent them from lifelong addiction and health hazards?

4. Has the proliferation of GMOs been seriously slowed until we can better understand its long-term impacts?

5. Do a majority of Americans even believe any of these issues are even an urgent concern…?

Along the same lines, how good are working conditions at the largest U.S. companies? How high are those worker's wages? Will Social Security be able to pay 100% of benefits after 2034? Are wildly speculative investments on Wall Street being well-regulated? Are U.S. healthcare costs coming down? Are CEOs being held accountable for corporate malfeasance…and if so, how many have actually gone to jail?

The answer to these and countless similar questions informs us about the direction the U.S. is taking, and how nothing that interferes with corporate profits or the astounding wealth of their owner-shareholders will be allowed to flourish as long as conservative Republican (and possibly even centrist Democrats) hold power. In short, elected officials friendly to corporatocracy need to keep getting elected to keep this gravy train in motion.

And so there is no cost too great to expend in order for them to win, and the highest concentrations of wealth in the history of the world have brought all of their resources to bear to perpetuate those wins. This is why a Blue Wave alone cannot triumph in November. Perhaps, if every single Left-leaning voter - together with every single Independent-minded voter - comes out to make their voices heard at the ballot box, it just might make enough difference. And I do mean every single one.

But a Blue Wave alone will probably not be enough. In effect, what America requires for a return to sanity and safety is what we might call a Blue-Orange Tsunami - perhaps even one with a tinge of Purple, where Independents, Democrats and the few sane Republicans remaining unite their voices and votes against a highly unstable fascistic threat.

Short of this, there is just too much money in play, carefully bending mass media, social media, news media, scientific research, legislators, election systems, judges, government agencies, public opinion and the President himself to its will.

REFERENCES

https://www.businessinsider.com/partisan-gerrymandering-has-benefited-republicans-more-than-democrats-2017-6

https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/how-the-gop-rigs-elections-121907/

https://www.cnn.com/2016/12/26/us/2016-presidential-campaign-hacking-fast-facts/index.html

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/alecs-influence-over-lawmaking-in-state-legislatures/

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/mar/19/facebook-political-ads-social-media-history-online-democracy

https://www.politico.com/story/2018/01/16/trump-california-census-342116

https://slate.com/human-interest/2018/07/james-gunn-dan-harmon-mike-cernovich-the-far-rights-pedophilia-smear-campaign-is-working.html

https://www.mediamatters.org/research/2016/03/16/lies-distortions-and-smears-how-right-wing-medi/209051

Thanks for the question Michelle. I must first admit that I’m not a good candidate for videos, as I find the format painfully slow in its conveyances of themes and perspectives. Instead, I read the following writing of Benjamin Cain (hoping to find similar points there) in order to answer the OP’s question:

Scientism and the Artistic Side of Knowledge

Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Scientism and the Scapegoating of Philosophy

Here is my take so far:

Cain is spot on regarding scientism — its sentiments are not a careful integration of the scientific method into our approach to knowledge, but rather

an arrogant attitude about the superiority of scientific pursuits over all other human aptitudes and interests — and of the dominion of human reasoning and worldviews over everything else in Nature (i.e. the anthropocentrism theme). In reality, of course, science is just one more facet of the human exploration (i.e. Cain’s pluralism), and humans are just one outcome of Nature’s vast experiments.

I’ve taken similar issues on myself in essays like this one:

Sex at Dawn: The Fallacies of Simulated Science — in which I attempt to differentiate between popular notions of science, and actual scientific thinking. Another attempt to broaden critical reflection and process beyond various patterns of exclusionary bias (including scientism) can be found here:

Sector Theory 1.0 — Todd’s Take on Epistemology.

Some caveats: When Cain’s criticisms of Tyson (in second linked essay) begin framing him within neoliberalism, I think that goes a tad too far. In reality, Tyson’s attitudes and methods may indeed lend themselves to perpetuating a neoliberal agenda (by supporting capitalism’s growth-dependent innovations)…but I don’t believe they are deliberately propagating the same. In the same vein, Cain tends to overgeneralize about “scientists” in ways that don’t help his arguments. Though Cain’s observations are appropriate for the culture of science and scientific institutions (and broader cultural attitudes towards science), they simply do not apply to “all scientists.” In other words, he would do better off using his term “scientismist” instead during any such rants. That said, the first linked essay, “Scientism and the Artistic Side of Knowledge,” is much more carefully constructed and worded.

All-in-All, I think Cain has some interesting things to say, and should be seriously considered as a contributive perspective. He does not promote, as Joe Velikovsky asserts in his post, “anti-science nonsense;” Cain’s perpective is neither anti-science nor nonsensical. He is simply asserting that, in a cultural, psychological and epistemic sense, “science is not the only story worth telling.” That is, science does not yet offer a complete picture of all aspects of existence and experience…

so why are so many folks so emotionally (and irrationally) committed to insisting that it does? Further, Cain argues that scientific knowledge itself is fraught with the same intuitive, prejudging shortcomings (or advantages, depending on your perspective) as all other human methodologies. Cain’s is a well-reasoned criticism — and I think it takes particular aim at the non-scientific use of scientific knowledge (i.e. scientism as a sort of religion).

One would think rational folks would appreciate that distinction….

My 2 cents.

Thanks for the A2A Dawn. To me it speaks to the synthesizing capacity of human beings in groups — especially regarding things like social roles and mores, expectations regarding prosocial behavior, definitions of wrong-doing, values prioritizations, constructs around “meaning,” prejudices, etc. — and that this can be both conscious and unconscious. In my discussions of “moral creativity” (see

L7 Prosociality) I promote the idea that we can have an active role in our own moral development and expressions…both individually and collectively…and that this will be reflected in the shape of our society. Our systems, institutions, cultural traditions, economic practices and so forth will reenforce and perpetuate certain assumptions about the world around us — and about the dominant forces within ourselves. The nature/nurture question is therefore more about our

ongoing chosen emphasis than any chicken or egg, as our interpretations of everything will conform to that emphasis. And although stepping back from such perpetuation requires effort, it isn’t all that difficult. Unless, of course, our investment in a given position is tied closely to things like perceived survival, thriving, loss, threat, power, status, belonging, cherished relationships, etc. In other words, we are only rigidly conformist when we believe the stakes are high. And that, unfortunately, is what those who wield power and influence are constantly trying to do: convince us that the stakes are high, and that we have a lot to lose by not conforming to a given narrative regarding “what is.” None of this has much to do with “truth,” IMO…only with the operational parameters of acceptable information. Does it threaten? Then it can’t be true. Does it console and comfort? Then it must be true. So the more we can be persuaded or coerced about the “acceptability” of some given information in this high-stakes context, the more likely we are to incorporate that information around our preexisting bias. All-the-while, the context may have been synthesized purely through fear-induced groupthink. This is how, as an enduring analogy, Golding’s “Kill the pig. Cut her throat. Spill her blood.” equates to

“Lock her up!” I.e. this is how we create reality distortions we believe to be true.

My 2 cents.

Agorism is Konkin’s Rothbardian wet dream, with some later infusions of counter-establishment activism. It is utterly confused and self-contradictory form of right-libertarianism — and to invest in Agorism (or even entertain Konkin’s ideas as well-reasoned) is to bend one’s own thinking into such pretzels as to potentially break important cognitive capacities. In part I think this is due to Konkin’s ignorance: for example, he misuses terms (like “Left-Libertarian”) without any understanding of their history or context. In part, however, this is just due to crooked logic; Konkin is kin to Ayn Rand in this regard.

Voluntaryism (not to be confused with voluntarism!) is a much broader container, built around mutual consent. As a tool to evaluate (and avoid) Statist impositions, it seems to be a useful concept. As a sort of moral standard, it is not as helpful. When married to capitalism (or defending property ownership, etc.), voluntaryism begins to twist its proponent’s thinking into rather nasty knots…like wage slavery being okay as long as it’s contractual (i.e. there is no recognition of coercive power structures).

I hope this was helpful.

Rand’s sins are legion, but here are the most egregious from my perspective:

1) Her misunderstanding and frequent misapplication of Aristotle.

2) Her promoting cigarettes as a “Promethean muse” that had no health risks.

3) Her unprincipled hypocrisy (in the same breath that she didn’t take responsibility for her cigarette-induced lung disease, she became dependent on the socialized safety nets she railed against).

4) Her bizarre assertions about human psychology, which really have no basis in anything scientific or even careful observations, but are purely Rand’s own inventions.

5) Her misunderstanding of causality regarding personal success, power and wealth accumulation (i.e. these do not materialize magically out of thin air as a consequence of individual effort or entrepreneurial spirit, but are wholly dependent on a supportive framework of civil society, generations of education and cooperation, the interdependence of human relationships, and — in Rand’s conceptions in particular — the availability of capital).

6) Her perpetual conflation of

rhetoric and emotional reasoning with

logic and objectivity. In other words, Rand would espouse various claims as if they were the consequence of logical argument, when they were really just layers of one fallacy upon another — with their fundamental justification being the sheer force of Rand’s personal will and imagination.

7) Her corrosive and destructive views about femininity, male-female dynamics, sexuality, romantic love, and even sexual intercourse itself.

Her astounding arrogance that, despite a great deal of evidence in support of everything listed above, Rand believed she was making a meaningful contribution to philosophical discourse…and that more people should follow her prescriptions.

My 2 cents.

To support a new framing of this longstanding issue, my latest essays covers many different facets and details that impact the polarization of Left/Right discourse. However, its main focus centers around the concept of personal and collective

agency. That is, how such agency has been effectively sabotaged in U.S. culture and politics f

or both the Left and the Right, and how we might go about assessing and remedying that problem using various tools such as a proposed "agency matrix." The essay then examines a number of scenarios in which personal-social agency plays out, to illustrate the challenge and benefits of finding a constructive solution - one that includes multiple ideological and cultural perspectives.

Essay link in PDF:

The Underlying Causes of Left vs. Right Dysfunction in U.S. Politics

Also available in an online-viewable format at this

academia.edu link.

As always, feedback is welcome via emailing

[email protected]

Thanks for the question John. I had to chuckle a bit when I saw this question…

The main challenge in any conversation — persuasive or otherwise — is that everyone share the same definitions of terms. If they don’t it will be impossible to communicate. In other words, we need to synchronize our knowledgbase. In this case, the terms “libertarian” and “socialist” have very broad definitions, and there is no better example of that than the fact that several answers so far confidently assert that it is “impossible” to persuade socialists to become libertarians, while at the same time I myself (along with countless others in the present day and throughout history) am a

libertarian socialist. So there’s the source of the chuckling. Ha.

Unfortunately, there are a number of barriers to education and subsequent knowledgeable synchronization. One is ideological resistance (we might call this “willful ignorance” that bubbles up from deeply cherished beliefs). Another is subjection to years of misinformation and propaganda. Another is a simple desire to avoid embarrassment when someone discovers their own mistaken understanding. Another is ego — just ‘wanting to be right,’ because that is very important to some people’s self-concept. There are other barriers, but these seem fairly common.

So how do we approach these barriers or mitigate them? First, although it’s fairly rare to do this successfully in today’s sociopolitical landscape, offering some educational resources may spark curiosity and willingness to be educated in some people. Sometimes just asking a person if they are interested in learning about X or Y can open that door. To that end, a person could be offered some or all of the following resources:

1) Watching a few of the plentiful videos of Noam Chomsky discussing socialism, liberalism, capitalism, libertarianism, and the language and history around these ideas. Here is one:

https://youtu.be/Qc6AgXVNNsY

2) Reading up on the history of anarchism, libertarian socialism and anarcho-capitalism in books like Marshall’s

Demanding the Impossible.

3) Appreciating how right-libertarianism (that is, capitalistic libertarianism) developed as a uniquely American flavor of libertarianism (via Mencken, Rothbard, Nozick, Mises, et al — there is a fairly good overview here:

Right-libertarianism - Wikipedia), and how it was then entirely coopted by neoliberalism (see

L7 Neoliberalism)

4) Appreciating just how pervasive, corrosive and distorted right-wing propaganda has become. Brock’s book Blinded by the Right might be helpful in this regard, and a Harvard study on how propaganda shaped the 2016 election can be found here: https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstre...

In any case, that’s a start. A person’s response to this initial exposure and education will help determine next steps. Are they surprised by what they learn? Are they willing to admit the extent of their own ignorance? Do they turn to poorly informed, knee-jerk polemics, ad hominem attacks or name-calling to reject the information? Do they express a thirst for additional information? How to handle each of these responses is a separate and often challenging question in itself.

I hope this was helpful.

Thanks for the question Pete. A number of verses come to mind, but to appreciate why they express nonduality may require some contemplation. First, I would recommend comparing parallel verses of what Jesus says about “the kingdom of heaven” and “the kingdom of God” across the gospels (i.e. Matthew 5:3/Luke 6:20; Matthew 19:14/Mark 10:13–14; etc.). and then just carefully examine what all Jesus says regarding that kingdom. That will be an eye-opener for some folks, and certainly speaks to nondual themes.

I would then turn to the Gospel of John, beginning with this:

John 17:20–23

“I do not ask for these only, but also for those who will believe in me through their word, that they may all be one, just as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, that they also may be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me. The glory that you have given me I have given to them, that they may be one even as we are one, I in them and you in me, that they may become perfectly one, so that the world may know that you sent me and loved them even as you loved me.”

And then some of the rest…

John 6:35–40

“I am the bread of life; whoever comes to me shall not hunger, and whoever believes in me shall never thirst. But I said to you that you have seen me and yet do not believe. All that the Father gives me will come to me, and whoever comes to me I will never cast out. For I have come down from heaven, not to do my own will but the will of him who sent me. And this is the will of him who sent me, that I should lose nothing of all that he has given me, but raise it up on the last day. For this is the will of my Father, that everyone who looks on the Son and believes in him should have eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day.”

John 7:16–18

“My teaching is not mine, but his who sent me. If anyone's will is to do God's will, he will know whether the teaching is from God or whether I am speaking on my own authority. The one who speaks on his own authority seeks his own glory; but the one who seeks the glory of him who sent him is true, and in him there is no falsehood.”

John 8:3–11

The scribes and the Pharisees brought a woman who had been caught in adultery, and placing her in the midst they said to him, “Teacher, this woman has been caught in the act of adultery. Now in the Law, Moses commanded us to stone such women. So what do you say?” This they said to test him, that they might have some charge to bring against him. Jesus bent down and wrote with his finger on the ground. And as they continued to ask him, he stood up and said to them, “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her.” And once more he bent down and wrote on the ground. But when they heard it, they went away one by one, beginning with the older ones, and Jesus was left alone with the woman standing before him. Jesus stood up and said to her, “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?” She said, “No one, Lord.” And Jesus said, “Neither do I condemn you; go, and from now on sin no more.”

John 10:34–36

Jesus answered them, “Is it not written in your Law, ‘I said, you are gods’? If he called them gods to whom the word of God came—and Scripture cannot be broken— do you say of him whom the Father consecrated and sent into the world, ‘You are blaspheming,’ because I said, ‘I am the Son of God’?

John 12:24–25

“Truly, truly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit. Whoever loves his life loses it, and whoever hates his life in this world will keep it for eternal life.”

John 15:4–5

“Abide in me, and I in you. As the branch cannot bear fruit by itself, unless it abides in the vine, neither can you, unless you abide in me. I am the vine; you are the branches. Whoever abides in me and I in him, he it is that bears much fruit, for apart from me you can do nothing.”

—————

These are some of the easier verses. There are others that require a bit more time and openness to grok and fully receive within a nondual context. For example, John 11:9 “Are there not twelve hours in the day? If anyone walks in the day, he does not stumble, because he sees the light of this world.” Or John 13:20 “Truly, truly, I say to you, whoever receives the one I send receives me, and whoever receives me receives the one who sent me.” IMO, both of these verses have not been adequately interpreted by most scholars, because they speak to a deeper, more unitive truth than is apparent on the surface (and even seems confusing).

My 2 cents.

There have been a number of proposals over the years that have attempted to “self-liberate” from what amounts to neoliberal oppression — many of which were proposed prior to neoliberal ideology even taking root. For example:

1) Various forms of counterculture — some embedded in the mainstream, and some retreating to isolated communes, etc.

2) Various top-down socialistic reforms that attempt to insulate entire segments of society — or all of society — from the impact of runaway crony capitalism through government programs, safety nets, publicly owned assets and services, etc.

3) Worker solidarity movements that permit organized labor to wrestle controls away from the owner-shareholder class.

4) The formation of a well-educated, affluent middle class with progressive values that can counter neoliberal agendas through NGOs, community organizing, community banking, electing progressive candidates, writing and passing progressive initiatives, and mass media counter-narratives.

5) Subversive activism that seeks to disrupt neoliberal agendas, such as hacktivism, sabotaging WTO meetings, ecoterrorism, etc.

6) Modeling alternatives that exit the self-destructive spiral of a neoliberal status quo. Low carbon lifestyles, Permaculture and

7) Transition Towns, becoming Vegan, and so on.

Thus far, such efforts have slowed the forward march of neoliberalism, to be sure…but neoliberal activists are themselves very skilled, well-organized and well-funded in their own efforts to move their plutocratic vision forward, often coopting counter-narratives and undermining radical efforts. Consider how the Koch brothers took over the Tea Party movement, for example, or how the Kitchen Cabinet manipulated Reagan’s populism to their own ends, or how a Patriot Act inspired by foreign terrorism empowered a neoliberal government to crack down more forcefully on its own citizen subversives, or how alternative culture has simply been been commoditized to further feed corporate profits, or how evangelical Christians in the U.S. are now almost totally in the thrall of the commercialist, corporationist Beast. It’s stunning, really.

Which leads us to the question: what else can we do, either individually or collectively? I think the desire to “check out” of a toxic political economy altogether, and hide ourselves away off-the-grid or in some developing country, can be very enticing. It’s also pretty selfish, however…in some ways playing right into the “I/Me/Mine” individualism that feeds the disintegration of civil society itself. Another, perhaps more responsible approach would be to try David Holmgren’s

“Crash on Demand or how to opt out the corporate fascism.” I think he has some good ideas there that could lead to major reform. But really I think the best method is to walk right past the low-hanging fruit, and aim much higher. Which means reforming the underlying political economy itself, rather than attempting a Band-Aid approach to countering neoliberalism. To that end, I’ve cobbled together a “multi-pronged” system for transformative activism here:

L e v e l - 7 Action. The basic idea is that if we work towards ALL of the threads of change agency described there, we just might be able to undermine a neoliberal status quo in enduring and sustainable ways. At this point it’s just my own vision, but hey…why not aim high? Why not try to alter the underlying, causal factors that keep leading us down the same self-destructive path…?

My 2 cents.

I’m fairly certain that Rousseau, Wittgenstein, Aquinas, Sartre, Marcus Aurelius, Hegel and many other great thinkers would heartily agree with this question's sentiment. It takes real courage to remain vigilant about our own epistemic assumptions — and the conclusions we reach while relying upon them. Add to this our natural fallibility, ego attachments, fear of what we do not comprehend, and tendency to cling to the comfort of what is familiar…and, well…our ship of inquiry will always crash upon the rocks of self-reference eventually. But that doesn’t mean we can’t build a new ship, hoist our sales and seek a new course of insight. We need only be cognizant the breath that animates that quest, the buoyancy of mind that keeps us afloat, and the awareness that steers our course. And yes…we can still “love the truth” as an unknown objective, as a glint of light luring us from just beyond the horizon; to intuit its presence or catch the briefest glimpse with some fragment of our faculties does not negate devotion. Indeed it can inspire it, despite our apprehension about probing the unknowable. Perhaps it is easier to fall in love with mystery — or what mystery evokes in our imagination — rather than with our own settled beliefs. Or at least the love feels more genuine, and less contrived and pretentious.

I think what often steers us back to the perceived safety of that rocky shoreline is our fear that we will drift without a compass, or sight of land, or lose the motivating pneuma that makes our sails swell so pregnantly with purpose. But the intrinsic passion for truth will call from the open ocean, even when we are rudderless and adrift in the doldrums of our gravest stupidities. Even into the last instant, when the parched intellect is sure of its extinguishment, there can be truth…and love of truth…if we are open to it. Which is why the comforts of the settled shore, the habitual status quo, the camaraderie of cracking fires and shared soup, the coddling sleep upon still rocks — even if all of these are equally mere inventions of the mind — will always still the seeker within more readily than death. And so the morning after is itself a revelation, a revision of each old truth with something new, if we are willing to venture once more out to sea. All the greatest thinkers experienced this, which is why their thinking evolved over time, and why they often abandoned initial modes and premises and foundations for a better design or broader vision…or dismissed their previous assertions as faulty precursors for a more precipitous leap into the vast unknown.

My 2 cents.

Basically Aquinas argues from the position that — logically, intuitively, observationally, analogically — there can't be an infinite regress of causes, and he does this along several lines of reasoning. In essence, in order for God to be God, that prime mover can’t have a preceding cause. It would negate the primacy (and thus the divinity) of that mover. To appreciate both the context and the details of his arguments, it would be helpful to read the entirely of his discussion on the existence of God at the beginning of

Summa Theologiae. You can read that online here:

The existence of God (Prima Pars, Q. 2)

What is an object? It’s a thing, right? Just a thing…basically only valuable in terms of its utility or commodification. Its function or someone’s desire for it determines its purpose and worth. But is that what a human being is? Just a thing…? A thing that it only valuable because of its utility or someone’s desire for it, and without any other essence or purpose? Is our only function to…ultimately…be objectified by others? To be used? Meditate on this for a bit. “Private property” is, in its most essential characteristic, the “thingification” of the world; that is, the forceful categorization and boundarizing of everything as “stuff.” That is,

as objects that are used, and only valuable because of their utility and desirability, and not because they have any intrinsic value or purpose that transcends material exchanges or the capricious whims of humans. Ownership is enslavement to the will of the owner. This is a pretty profound observation, don’t you think? And yet it escapes most people that everything they do — and everything they are — in a capitalist system distances them from their own intrinsic, non-material value, and turns them into an object…a slave. Thus private property, as the primary building block of a capitalist system, ultimately results in the commodification of the human spirit…and in a society that is mired in cultural poverty and alienation.

This is what Marx is getting at with his theory of alienation and “self-estrangement.” And IMO it is incredibly important to understand this component of Marx’s thinking,

because everything else in his philosophy flows out from this central observation. Thus the capture and imprisonment of all natural things into a state of “private property” destroys their inherent value — strips them of their essence — and replaces that inherent value with commodification. In the same way, the “commodified” human being relinquishes their will, their choice, their imagination, their self-determination, their creativity, their social relations and fundamental purpose…purely in order to serve the will of profit. To be a slave.

To be a thing. When understood in this way, it is no surprise at all that Marx was so opposed to private property. As comprehensive definitions of “evil” in humanistic terms, private property’s annihilation of our humanity presents a fairly compelling case. It does require some thoughtful effort to awaken to this perspective…but once we wake up, it’s pretty hard not to see why Marx was so passionate about moving beyond the capitalist status quo as quickly as possible, and to return all “property” to the commons.

For my own take on the problems with private property, please consider reading this essay:

IntegralLiberty.pdf

My 2 cents.

Great question — thanks Danijel.

So here’s my take….

1) Some words are purely representational and symbolic.

2) Some words — or bodies of words — may actually embody the essence-of-a-thing, or “the thing as-it-is.”

3) And some words or bodies of words may actually

create a thing.

In my view these three different operations of language are usually unconscious — humans don’t, in general, actively navigate the world around them via consciously ‘code-switching’ between these operations. Some may try to do this…usually those who have spent their lives intending to either a) understand and appreciate their own consciousness and agency in the world in an intuitive and introspective way, or b) have been educated about a particular approach to consciousness and agency in a systematic way. Still, extensive mastery of language in this context is IMO extremely rare.

Some examples will probably be helpful here. The first case —

pure representation — is fairly easy to grasp and likely needs no examples (it seems as though the question itself is predicated on this assumption). The second case,

embodying essence, is perhaps a fundamental function of consciousness itself, as evident in an infant’s gurgling as it is in a poet’s gift or a mystic’s insights. We see this in the phonemes “ma,” “muh” and “meh” which are an almost universal component of all the words referring “mother” or “motherly” in any language. How is this possible, unless there is some basic, essential unity-of-association between a given sound and its particular representation (or evocation) in our emotional experience…? In other words, in some instances a given word touches upon “the thing as-it-is” —

at least in the context of universal human experience and response.

Poetic and mystical examples follow along similar lines, with kindred or identical sounds, words and phrases in many different languages (which do not share common linguistic roots) evoking similar meanings, contexts or experiences. Atman, alma, anda, pneuma, arima, anima, anam, jan (жан), neshama (נֶפֶשׁ) all relate to spirit or soul, for example. Likewise, metaphors that relate to happiness as a “rising up” experience are cross-cultural, near universals, as are idioms expressing anger or frustration that relate to being enclosed and

trying to get out. Some linguistic theorists surmise that such universals reflect our common neurophysiology, or parallel developments in culture, and these are certainly viable explanations. Some behavioral scientists have even suggested that “moral grammar” — and the culture that arises around it — is itself a feature of our biology. Another explanation is that there are universal patterns, structures, energies and processes that occur on a quantum level across all of biology and consciousness — again, just a theory. And, adding to the mix, there are also intuitions of a unitive principle behind all consciousness and spirit. These theories are themselves

representations from one perspective. From another perspective they are sussing out a shared ground — of being, becoming, evolving, a common cascade of interdependencies, and so on; that is, they are

embodying essence. Personally, I’m willing to bet that all of these theories offer a piece of the puzzle (that is, that all of them have some degree of descriptive accuracy).

Lastly, we come to

creative language. On one level, this idea is as simple as one person writing fiction, and another “experiencing” that story as a felt reality in their own mind. On another level, there is the suggestion that language itself has formative and projective capacity on human development and activity (Sapir-Whorf, etc.) — movements like “nonviolent communication” have been heavily influenced by this line of thinking. And on yet another level, there is the concept of

logos within various Christian and Hermetic traditions, and the panentheism across various other traditions, that link mind and language and unfolding reality in interpenetrating ways. Even certain schools of philosophy have addressed the possibility of the projective capacity of mind on reality (from various forms of dualism all the way up to quantum consciousness), and here language can become a component of that projection as well. I’m covering a lot of ground here that probably requires more detailed elaboration, but the basic idea is that “a word” is much more than a description of a concept — it has its own substance, its own energy, its own essence, which links it more directly to the

creation of other phenomena.

So this is a fascinating question, with substantial capacity for ever-broadening exploration. The danger, I think, is trying to reduce language and thought to mere

representation, when there may be a lot more going on….

My 2 cents.

Comment by Danijel Starcevic: "Really interesting perspective, especially the part about the “ projective capacity of mind on reality”, with language being a component of that projection. Are there any modern scientific inquiries into this?"

LOL. No. At least not mainstream stuff. Bohm’s “implicate order,” Sheldrake’s “morphic resonance” and László's “Akashic field” theory are about as close as you’ll likely get to actual science along these lines — and the implications for language are mostly my own, even in those instances. Interesting reading though.

Most of what I’m referencing is more esoteric in nature. Can it be directly experienced? Sure. Can it be replicated in a double-blind experiment? Not so much. I’m wondering if “the observer effect” actually has an impact on this — trying to measure something that reacts to the measurement instrument. Just a thought….

Since the OP used a lower-case “l” for “libertarian,” I’m assuming this question is not restricted to U.S.-style right-libertarianism, that is…“Libertarianism” with a capital “L.” Left-libertarianism, which has been the dominant school of libertarian thought around the globe for many decades, has a tremendous overlap with with progressivism. In fact, you can’t really differentiate a “progressive” from a left-libertarian, as their goals are identical. The only reason

methods may differ is that “progressivism” does not distinguish or emphasize one system of government over another — it is primarily focussed on improving freedoms, well-being, opportunities and conditions for everyone…by any means possible. Libertarianism, on the other hand, is opposed to State-centric solutions, and solutions that impose the will of any number of folks on everyone else. Essentially, progressives aren’t as picky about government, as long as government is moving a progressive agenda (civil liberties, economic opportunity and stability, scientific knowledge and education, etc.) forward.

Now…in the U.S. specifically things have become very different around these terms/ideologies. Why? I discuss some of the reasons why here: see

“How has (Tea Party) Libertarianism become conflated with or gobbled up by anarcho-capitalism and laissez-faire capitalism in the U.S.A.?” at this link

L7 Neoliberalism. Basically, pro-capitalist ideologies have almost entirely captured Libertarian thinking in the U.S., whereas throughout the rest of history — and throughout the rest of the globe — left-libertarianism has been markedly anti-capitalist, even though many left-leaning forms of libertarianism are still pro-market and pro-competition (the left-right division here centers around private property…but that is another discussion). At the same time, those who self-identify as “progressives” in the U.S. have tended to be pretty pro-Statist in how they aim to solve problems. Essentially, then, even though the underlying objectives may be very similar, the methods of U.S. progressives and U.S. Libertarians are in opposition, with

“government can’t do anything right, and taxation is theft,” on the one hand, and

“government offers the best solutions, as funded by higher taxes” on the other. That’s a pretty extreme tension.

Of course, the neoliberal, laissez-faire, Austrian School, Randian objectivist and other market fundamentalist folks are generally

delighted that right-libertarians (many of whom will self-identifity as anarcho-capitalist or “AnCap”) have joined their club. Personally, I think this is very sad, as it is a gross distortion of traditional libertarianism to believe commercialist corporationism supports liberty. It doesn’t. Instead, it reliably produces slavery. Even if, in Nozick’s words, that slavery is “voluntary,”

it’s still slavery, and not freedom. This is a more complex discussion, but you can explore the subtleties of the issues involved my essay here:

IntegralLiberty.pdf.

So, as others have pointed out in their answers, it really would be great if right-libertarians in the U.S. recognized how much more common ground they have with progressives than, say, with right-wing religious conservatives — and for U.S. progressives to recognize how much more common ground they have with a right-libertarian vision of civil liberties than with, say, neoliberal “centrists” like the Clintons. Really the only folks who reliably win from these divisions are crony capitalist plutocrats…and so, IMO,

it would be great if Americans woke up to this reality and formed some anti-neoliberal, pro-democracy coalitions.

Yes Marx’s concept of surplus value is still relevant. But it really, really bothers neoliberal propagandists, Austrian School pundits, and other market fundamentalists that anyone is still brazen enough to use the term. These pro-capitalist folks will rail against its usage and belittle anyone who believes that this or any other ideas from Marx are still relevant. But don’t let them distract you. I think you are on the right track if you are trying to understand Marx’s insights through a modern lens. Probably the best modern example that conforms to Marx’s concerns about “surplus value” is the power that wealthy shareholders who purchase a lot of shares have over how a company does business, and the benefits that they reap from that involvement. Such a person might own a large amount of stock in a company and, even though that stock is a very tiny fraction of their own personal portfolio, they might wish to exert enormous influence as, say, an activist investor. They are, essentially, trying to maximize their personal profits — and this always comes at the expense of workers and consumers. A recent example is what happened at Qualcomm, which now has to execute a huge employee layoff to satisfy investors after the failed Broadcom takeover bid (again, to increase profits). These investors are not adding any value to an enterprise, they are just trying extract value from it. This is the concept that Marx was trying to “prove” with his surplus value calculations in Capital III — and, if you bypass the math, and instead examine the spirit of what Marx was trying to say about exploitation and the profit motive, you’ll begin to grasp the scope and intent of his insights.

A similar concept, and one well worth researching, is “rent-seeking,” where someone manipulates an environment to increase personal or corporate profits (such as lobbying or regulatory capture, for example), again without adding any real value to the equation.

Now it is easy to pick apart Marx’s arguments in Capital, and to say that certain details of his calculations are no longer relevant. But this entirely misses the narrative that Marx was trying to construct about the nature, methods and consequences of capitalism. And that narrative is very much still true today.

My 2 cents.

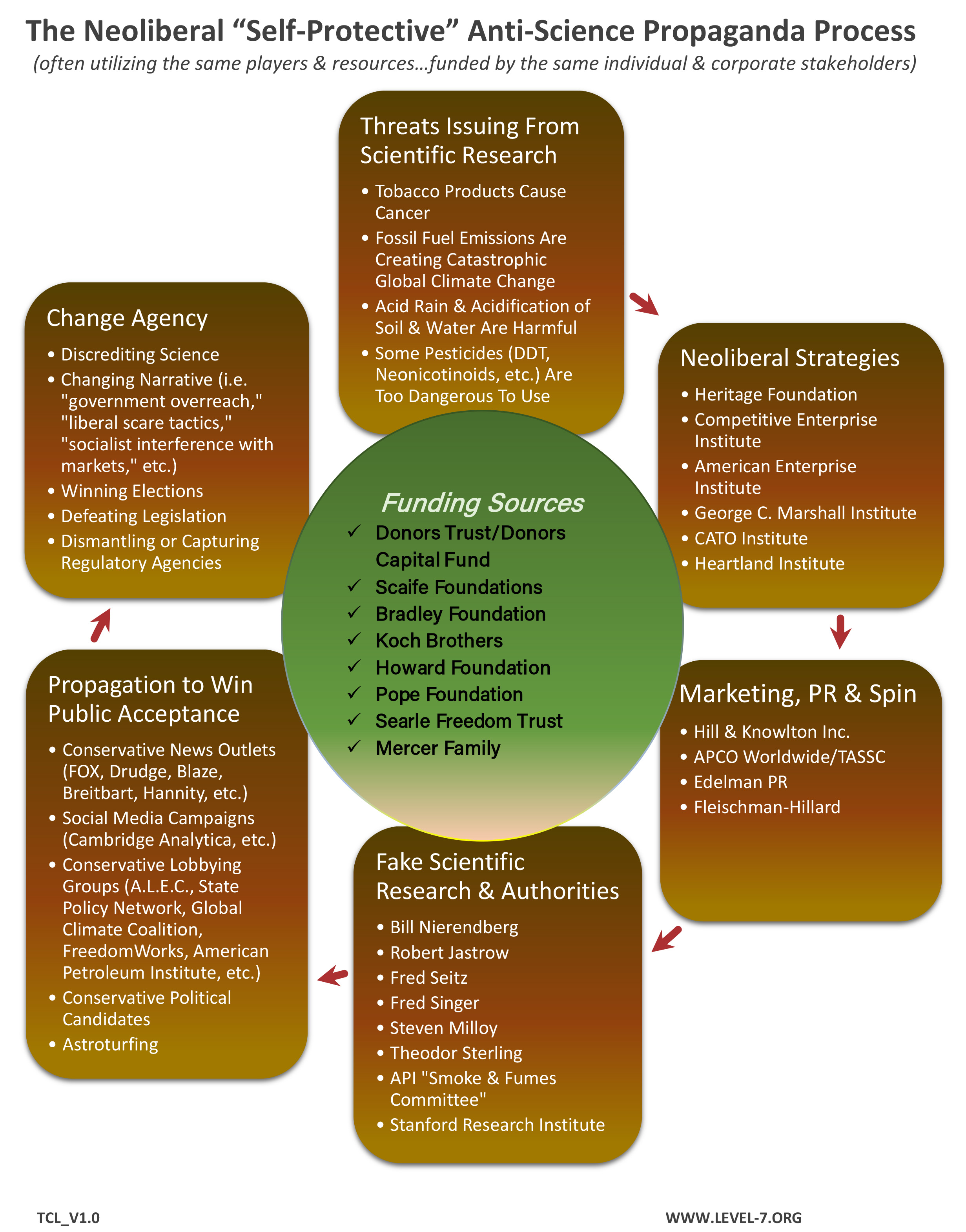

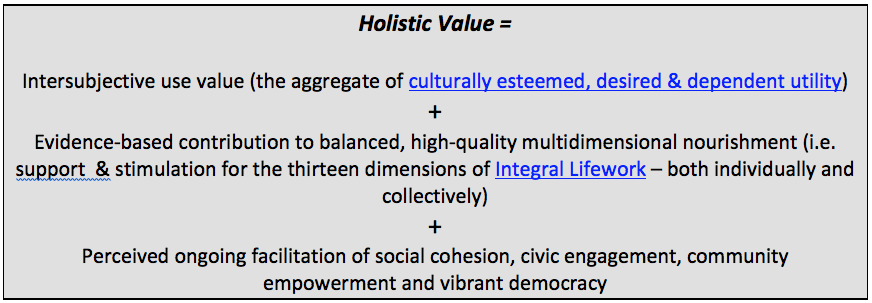

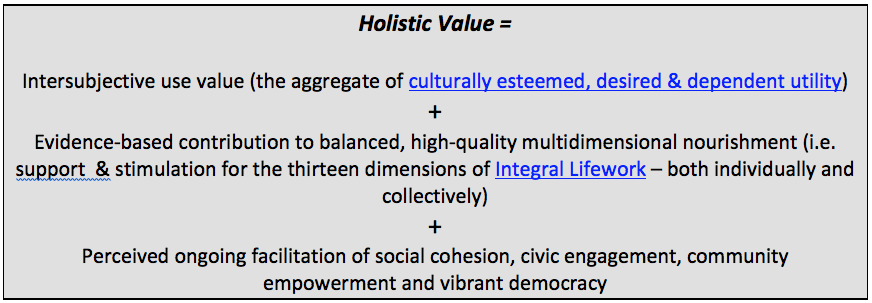

Hi Carl — thanks for the question. I suspect our fundamental attitudes about valuation are not that far apart, as we have both come to similar conclusions about that which is “life sustaining” having authentic “value.” I attempt to address this in my consideration of “holistic value,” but that formula also includes human-perceived-utitilty as part of the calculus. Anything that contradicts or undermines holistic value (but nevertheless commands high exchange value) is categorized as having “perverse utility.” There is a brief overview of the concept here:

L7 Holistic Value, and here is how I summarize and expand on it a bit in my essay “

Reframing Profit”:

“In Level 7, for-profit and non-profit designations can be addressed to some degree via the collectively designated holistic value for a given product or service, as this valuation process will inherently expand or contract potential profitability. How do we arrive at holistic value? In brief we can apply the following formula, which expands slightly upon previous conceptions described in Political Economy and the Unitive Principle:

As part of this process, we can even target the "fulcrum's plane" of ideal nourishment to refine holistic value with objective metrics – metrics which can then be made available to all via the Public Information Clearinghouse.”

Now this essay (as well as what I cover in the

Unitive Principle book) is really discussing

a transitional state of affairs. It is a compromise that attempts to reconcile human machinations and culture with Nature’s underlying order (as embodied in Integral Lifework’s “multidimensional nourishment” and

the unitive principle itself). To appreciate what I’m aiming for here, I recommend reading the entire overview of

L7 Property Position. I believe you will intuit what I’m headed with these ideas…

Looking forward to your thoughts Carl.

My 2 cents.

Comment from Carl Leitz: "Brilliant and deep insights here - it's discouraging to realize how much more we need to know just to be able to scratch the surface of what there is to know."

The challenge, I think, is that we are still in the relative dark ages with respect to developing an ethical and egalitarian political economy. Not just in conception, but in the groundwork necessary for implementation. So a lot of fundamentals have to be revisited — and in some cases reinvented. And we can’t always rely on all of the tools or concepts (or language) already in use, because they are…well…essentially toxic. But they are also complex, and well-established. So it’s a bit like saying to the modern economist: “Hey, so we need to stop using leeches. Yes, I know we have been using them for a while, but they don’t really work….” And the reaction is often, I would suppose, not unlike how the “doctors” of the middle ages would have reacted: incredulity and reflexive rejection of the truth. (sigh) So we have a long way to go….

What an interesting assumption! I think I’ve always been a socialist at heart, so various socialist proposals have resonated with my native sensibilities whenever I encountered them. So at first I didn’t really think any particular speech had ‘lured me into the fold’ as it were. But as I thought back, I then remembered listening to Ronald Reagan once, when I was about fourteen and living in West Germany, and realizing even at that age what an incredible idiot he was, and this, in turn, sparked me into deeper thinking about much of what Reagan seemed to be trying to do with his policies and rhetoric. At that time, I also recalled that a representative from an Oil and Gas company who had given a lecture at a local High School near me (this was back in the States, before I left for Germany) sounded strangely similar in both tone and nonsensical language. There was a similar easygoing, deceptive slipperiness in them both. And so something “clicked” for me at the time — something came together about being lied to by public figures who were trying to get people to support a given outcome. And what was that outcome? What were these liars and cajoling buffoons trying to persuade people to do…? It was answering that question, I think, that somehow watered the seeds of socialism deep within, and recalled to my mind the songs of Pete Seeger that I had listened to as a youngster, and indeed learned to sing myself. Songs like John Henry, Where Have All the Flowers Gone, If I Had a Hammer, This Land is Your Land, Waist Deep in the Big Muddy and many others; songs that instilled a sense of pride and rightness around a love of justice, a shared sense of place and purpose with folks from all walks of life, and a mistrust of rigid rules, institutions and authoritative systems.

What began to emerge was a realization that those who craved power and wealth — and deceived others into supporting their efforts — were the same folks who liked to impose rigid rules and perpetuate authoritative and destructive systems that benefitted themselves. And these folks were, by self-identification, nearly always devoted capitalists and corporatists. And I think that, within this ripening context, when I was introduced to the New Testament, I found it particularly striking that Jesus and his followers so pointedly amplified freedom, generosity, justice and kindness for the common and oppressed person, while ridiculing and reviling those wealthy, authoritative power-brokers of their time who were perpetrating most of the oppression. It was all coming together nicely, you see? And so, many years later, what was probably a timely anointing of this gestation process was encountering the work of Noam Chomsky, whose clear and unapologetic voice indicted the very same oppressive systems and institutions, while lauding the benefits of socialistic and anti-capitalist sentiments and practices — in his case leaning towards left-anarchism. Taken altogether, it was quite a tapestry of influences that all ultimately converged on libertarian socialism. But, really…when it comes right down to it…it was that one absurd speech from Ronald Reagan that nudged me most forcefully away from everything crony capitalism has come to represent, and indeed what it still perpetuates in our modern political economy.

My 2 cents.

Politicians? I wasn’t aware they cared about democracy at all. They certainly don’t in my country (U.S.A.). Thanks to the dogged efforts of neoliberal owner-shareholders, U.S. democracy has become little more than crony, clientist state capitalism. “Representative” democracy mainly represents a relatively small number of wealthy owner-shareholders, not the broader electorate who has been hoodwinked into voting against their own interests.

As for intellectuals, I think the promotion of direct democracy and consensus democracy are often discussed in a future-looking way by academics because these approaches hold a lot of promise, and have been fairly successful wherever they’ve been tried.

Yes, I do believe intellectual capacity is decreasing in the developed world, even as it increases in developing countries. However, it doesn’t require a brilliant intellect to envision or practice new forms of direct or consensus democracy. It just requires a bit of education, a level moral maturity that recognizes the importance of civic responsibility and participation, and an attenuation of “I/Me/Mine” economic materialism.

My 2 cents.

Is this a college essay question? I hope not.

Rawls’ maximin preference has nothing to do with risk aversion. This is a misreading of the context for his original position. He simply emphasizes that a system that minimizes negative outcomes and opportunity costs in fundamental ways will maximize potential benefits across all of society — including the ability to take future risks. And because decisions from the original position inherently aim to decide pervasive systemic foundations for everyone in society, hogtying the proposed universality of justice and fairness for the sake of some minimal, targeted perceived utility is…well…it’s just shortsighted. Even if that perceived utility appears to be a form of freedom, the cost is simply too great (again, within the pervasive and perpetual context that Rawls has defined for this exercise) to sacrifice what I would call the foundations of freedom itself — i.e. what Rawl’s discusses as the social minimums of liberty, opportunity, education, etc. for everyone — in order to facilitate some much more narrowly defined goal. In this respect, arguments against Rawls do tend to be a bit myopic and blinkered. Remember that Rawls’ veil of ignorance demands such systemic conditions be optimally defined without any knowledge of one’s position, resources and opportunities. Thus maximin becomes a sensible starting point for that discussion.

My 2 cents.

Absolutely. AnCap likes to frame “coercion” as a feature of the State, but ignores how it also manifests in free enterprise. Capitalists regularly coerce consumers and workers — regardless of whether the State aids or legitimizes these actions. This is true even for small business…not just monopolies. But monopolies — which can occur (and have occurred) naturally, and without mechanisms of the State — often amplify the scope and intensity of that coercion. Capitalism, by its very nature, encourages coercive practices — the company store, truck systems, share cropping, wage slavery, debt slavery, deliberately addictive products and services, brutally non-competitive practices, deceptive manipulation of consumers through fear and threats, etc. have always surfaced spontaneously in capitalist systems — and thus there is really nothing inherently “free” about a free market. Most market fundamentalists, including anarcho-capitalists, will rail against these characterizations of inherent coercion…but I’ve yet to encounter a valid counterargument that wasn’t steeped in neoliberal hoodwinking, irrational knee-jerk bias, ideological groupthink, and unsubstantiated beliefs about “unicorn” economics. Folks will just want to believe what they want to believe, and when you get a large enough group of them agreeing on what are often bizarre cognitive distortions, no amount of reasoning “from the outside” can free them from their delusions. It’s a sad state of affairs for the human species, and if we can’t break free of these immature, tribalistic mindsets, it does not bode well for our humanity’s future….

My 2 cents.

So I think there are a number of different things to consider here, and that they often get conflated into a single, overarching criticism of Marx. They include:

1. The issue of Marx’s LTV itself, and of what constitutes

surplus value.

2. The issue of Marx’s definition of (and solution to ) “the transformation problem” of how commodity LTV-based values convert into exchange values.

3. The conclusions that Marx draws, in part from these first two issues, about the inevitability of workers rebelling against the capitalist system, and the form that will take.