I think that’s actually pretty simple. Here are a few things that would help roll back extremist influence in society very quickly:

1) Reinstate and vigorously enforce The Fairness Doctrine in all news media — including social media (which, really, is just another platform for news media propagation). This would greatly reduce propaganda news outlets at both ends of the spectrum.

2) Reverse the divisive rules changes in DC that have prevented bipartisan dialogue and compromise: Abolish the Hastert Rule in the House; reverse Gingrich’s three-day work week and return it to five days, encouraging members of Congress to remain in DC and foster cross-the-isle relationships (this is what Gingrich wanted to destroy…and it worked); and so on.

3) End gerrymandering and voter disenfranchisement. When large numbers of folks feel like their views and priorities are not represented by elected officials, they become more extreme in their views.

4) Increase direct democratic controls over ALL legislation (via referenda, etc.) up to and including at the federal level, and allow recall elections for ANY misbehaving elected officials (all the way up to US Senators). More effective and immediate democracy is a great mitigator of extremism — at least it tends to be over time.

5) Completely ban all special interest lobbying and enact sweeping campaign finance reform (for example, allow only public funding of campaigns).

6) Institute a public

Information Clearinghouse of reviewed and rated information that helps folks navigate complex issues in order to vote on them in an informed way.

I’ve offered some additional ideas here:

L7 Direct Democracy

And if these are simple ideas, why haven’t they happened? Why, indeed, have they been vigorously opposed? Well, because the neoliberal plutocrats who hold most of the power are quite happy to perpetuate division and extremism to manipulate voters and legislators into doing their bidding. It’s very transparent, and has been going on for a long time in the U.S. and elsewhere.

My 2 cents.

Thanks for the question.

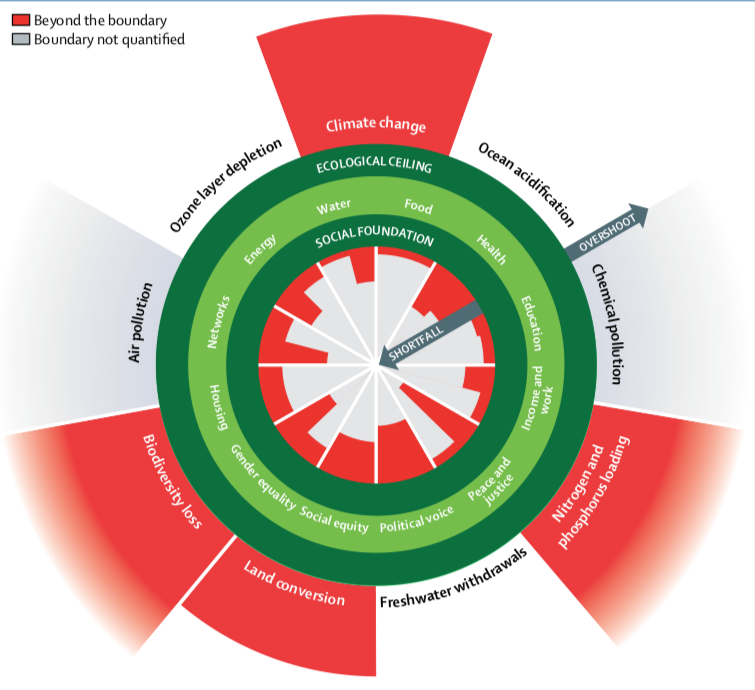

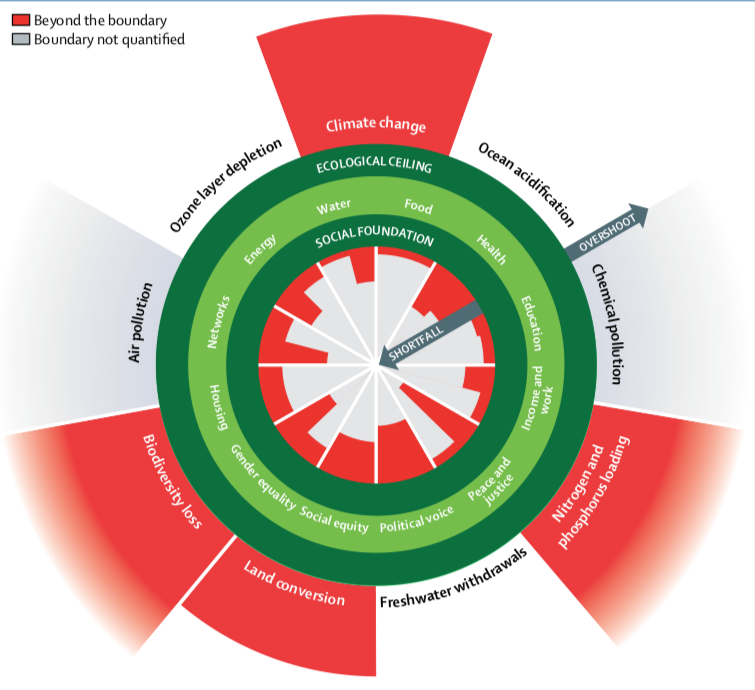

Personally I appreciate the simplicity of Raworth’s model (pictured below, from

https://www.kateraworth.com/doughnut/). There are undoubtedly nuanced variables within her “shortfall” and “overshoot” trajectories that require much more detailed elaboration, but this is really about vision IMO — and the ability to project that vision out into collective consciousness. The doughnut graphic is really helpful in that regard. So, as a fundamental re-framing of socioeconomic activities away from “infinite growth” (inherently unsustainable) to “living within our planetary boundaries,” I think this makes perfect sense.

So there are a number of facets with the OP’s question: “Why did the left follow Marx and not Bakunin? Wouldn't the world have been better off if a stateless form of socialism had been tried instead of a totalitarian one?” I’ll attempt to address those facets as we examine some possible answers….

1) The “Left” is not monolithic now, nor was it ever…from the very beginning. There were (and are) many forms of socialism — and many of them have been (and are being) tried in different parts of the world, and on different scales. This includes many forms of left-anarchism/libertarian socialism that aligned itself with the stateless vision that Bakunin promoted. In particular, societies inspired by Proudhon and Kropotkin fall into this category. For some of the many successful stateless examples of these, see:

List of anarchist communities.

2) The thinking of these two influenced each other — there was a lot of cross-pollination between them. Much of Bakunin’s thinking is reflected in Marxism.

3) As to why Marx was generally more popular that Bakunin during their lifetimes and thereafter, there are a number of compelling theories, and frankly I don’t know which of them is correct. It could be that Bakunin was over-invested in leveraging the “educated elite” of his day to start a revolution and tended to ignore the working class, whereas Marx appealed more directly to the working class instead. It could be an issue of personal charisma. It could be that it was difficult for folks to envision Bakunin’s stateless society (as it still is today), but much easier to entertain the more gradual transition to communism that Marx proposed, along with his very catchy “dictatorship of the proletariat.” It could be that Engels’ eloquent and persistent championing of Marxism furthered it in ways with which Bakunin’s legacy and alliances simply couldn’t compete. Again, I don’t know. There has been much written about this…so perhaps doing more extensive research on this will help.

4) Yes, the world would be better off with stateless socialism. For a glimpse of that world, take a look at the list of anarchist communities in the link above. Some of them are still around and going strong.

My 2 cents.

Absolutely and without question, YES, as Marx was arguably one of the most important and influential thinkers of the last 200 years.

That said, I would recommend beginning with some of his shorter pieces of writing, just to get a flavor and overview of his thought, prior to attempting

Capital. And, when approaching

Capital, I would take it in small chunks, rather than all-at-once.

But yes, for anyone who wants to understand much of what the past couple of centuries of human history — and especially the impact of industrial capitalism — are all about, Marx is an essential read. To not read him (or discount him, as some have done in posts here) is

simply to remain ignorant and/or deceived about both the nature of capitalism and the nature of Marxism.

Interestingly, in reference to Adam Smith, Smith raised many of the same concerns about unfettered capitalism that Marx addresses in his writing — Marx just did so to a much more detailed and rigorous degree.

As to where to begin, I recommend the following links (to be read in the order they are listed). I think anyone who reads them with an open mind will be duly impressed with Marx’s clarity and accuracy of insight:

Marx 1844: Wages of Labour

Profit of Capital

Marx 1844: Rent of Land (note that Marx cites Smith extensively here)

Estranged Labour

Economic Manuscripts: Capital Vol. I

And of course it also helps to read a bit of Engels, particularly this:

Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy

Lastly, for a well-organized collection of — and access to — Marx’s work, I recommend this link:

Marx & Engels Selected Works. It includes “a short list for beginners” which covers a lot of ground. However, I would still begin with the above-listed links first, before diving into anything else, as they provide helpful context for everything else.

My 2 cents.

Thanks for the question, Jeff.

I’d say “that depends.” It depends on the the training of the therapist, their level of moral development, their own personal ethical praxis, and the system within which the therapist is practicing. This introduces a lot of variables. For a client-centered practitioner who is forced to maximize client load and minimize interaction time in service to group practice profitability, corporate cost-saving mandates, or a paucity of insurance coverage for their chosen modality, all but the most bare-boned moral and ethical assumptions can practically be followed. And even then, it may only be according to the letter of the law, rather than its spirit. That said, the APA has developed a very robust Ethical Principles and Code of Conduct:

https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

Given that some methods like CBT and DBT have a mountain of evidence to support their efficacy, one could conclude that “all that really matters is to effectively teach these helpful cognitive behavioral tools, and the rest is up to the client’s willingness and compliance.” And there are certainly many therapists who either lack the internal psychosocial makeup to transcend this position, or who become exhausted enough by the constraints of for profit practice, that they arrive at this pragmatic distance from their clients.

But there are many therapists — and I would argue the really “good ones” — who recognize that their practice is really about relationship. That relationship has boundaries, to be sure, but it is deeply empathic, deeply committed, deeply involved in the client’s well-being. It is authentically engaged in the client’s perspective and felt reality, rather than merely prescriptive. And it is actively adapting to the client’s individual needs, rather than treating them as another cookie-cutter application of proven principles. In short: it embodies love.

In this latter, and arguably rarer, case, the unspoken moral and ethical assumptions run much deeper that the APA guidelines. The relationship isn’t just about client benefit, avoiding harm, and navigating a maze of laws — that’s a given. It is also about compassion, attentiveness, empathy, and a profound honoring of the client’s agency and personhood. And why is this considered important — if not critical? Because most “good” therapists know that a client’s trust, openness, and empowered agency are not just sacred and precious in the abstract, but are also primary factors in healing, growth and transformation itself. These features of the client relationship will contribute to potential outcomes in much more enduring and arguably richer and more fundamental ways.

So on the one hand there is the efficacy of technique, and on the other there is the efficacy of relationship. Whether this position is a common or not I will leave for others to judge and comment upon. I would say, however, that it is essential.

My 2 cents.

Comment from Jeff Wright:

I wonder if you’d be interested in taking it another step (because I could not make this more explicit in the original question)—

What are the unspoken moral and ethical assumptions that delimit what is and is not in the APA guidelines (since they represent a kind of social consensus reality orthodoxy about the relevance or absence of such themes within mainstream practice)? What would “run much deeper”?

This involves your highlighted themes of client, agency and personhood, so there are embedded implicit ideas about the nature and extent of those notions. And I believe those are the key points in any (deconstructive or reconstructive) inquiry into the sociology or philosophy of psychology and its practical applications. I was going to say “clinical applications” but that is a good example of a relevant tacit assumption.

And to put this in a less abstract frame, are you aware of ways that practicing therapists engage these questions in their own work, with or without the ability to articulate them?

To further answer the deeper, tacit moral and ethical assumptions question, here are some possibilities — perhaps not universal, but I suspect pervasively involved once again with the better/best therapists:

Client independence from care. That is, a level of health, wholeness and harmony that allows the client to be free of any form of mitigation or ongoing clinical support.

Client happiness and equanimity. Beyond mere increases in function, a desire for the client to feel fulfilled, at peace, etc.

Client momentum towards emotional growth and moral maturity. There are inevitably more profound evolutions in people when they engage thoughtfully in self-aware therapy. The hope is that they will really “grow up” beyond the infantilized and/or traumatized state in which they first presented. More than independence from care, this is about self-transformation.

Most importantly, that the therapist does not interfere with any of these liberating processes and conditions, but actually facilitates them earnestly and devotedly.

Comment from Jeff Wright:

Thanks. These are good statements of the main positive ideas of humanistic psychotherapy, the ideals of the “better/best therapists”.

However, tacit ethical assumptions are not limited to positive and aspirational ideals, the traditional moral focus on virtues, the “this is our best version of who we want to be”. They also embody negatives or shadow features. It’s possible I think that practitioners who work in public service settings are probably both more embedded in these and more aware of them, compared to those in private practice who work with voluntary, aspirational clients (“improve my life” or “suffer less”, or “be happier”).

There are assumptions that are widely operative within psychology and psychotherapy that express a “medical model” (based on various forms of scientism) pathology, disease, mechanization, depersonalization, individualization, disconnection and isolation of the person from their family, world, depoliticization, a turn away from social issues, and so on.

To understand some of these themes, one thing we can do is look at what gets initially emphasized and more easily carried forward through a paradigm change. For example, there were attempts at spiritualization in psychotherapy (a.ka. “transpersonal”), which never became mainstream, and more successful attempts to import ideas from Buddhism (e.g. “mindfulness”), and now more recently, “positive psychology”, which seems more successful at gaining traction in research-oriented psychology.

All true. I think what you’re touching on becomes much more specific with the modality/philosophy of care involved. Some are more somatic while others focus on relationships; some incorporate transpersonal considerations while others focus on cognitive-behavioral tools. With so much variation, it becomes difficult, I think, to make broad generalizations about pervasive moral and ethical assumptions. But it’s worth a try nonetheless!

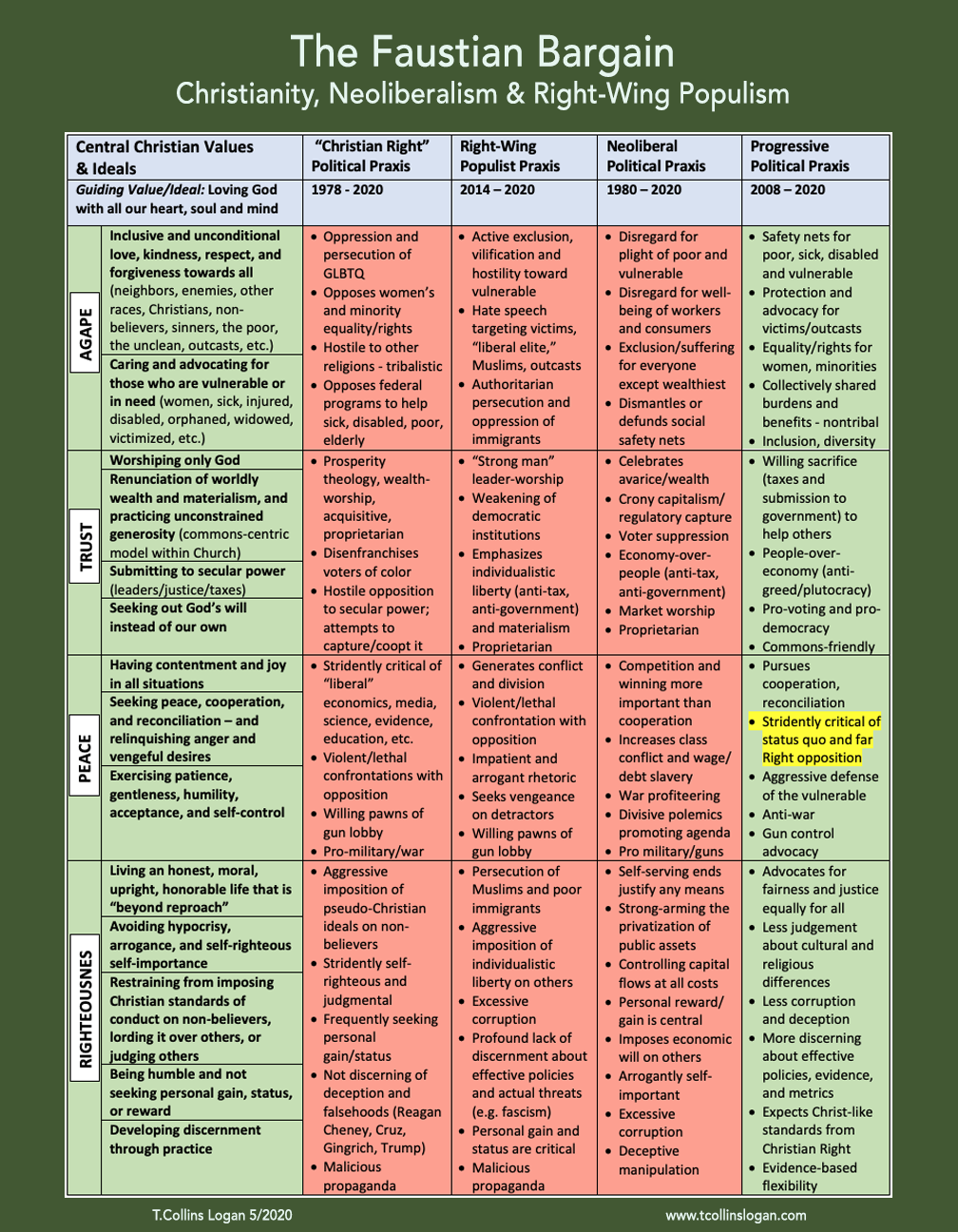

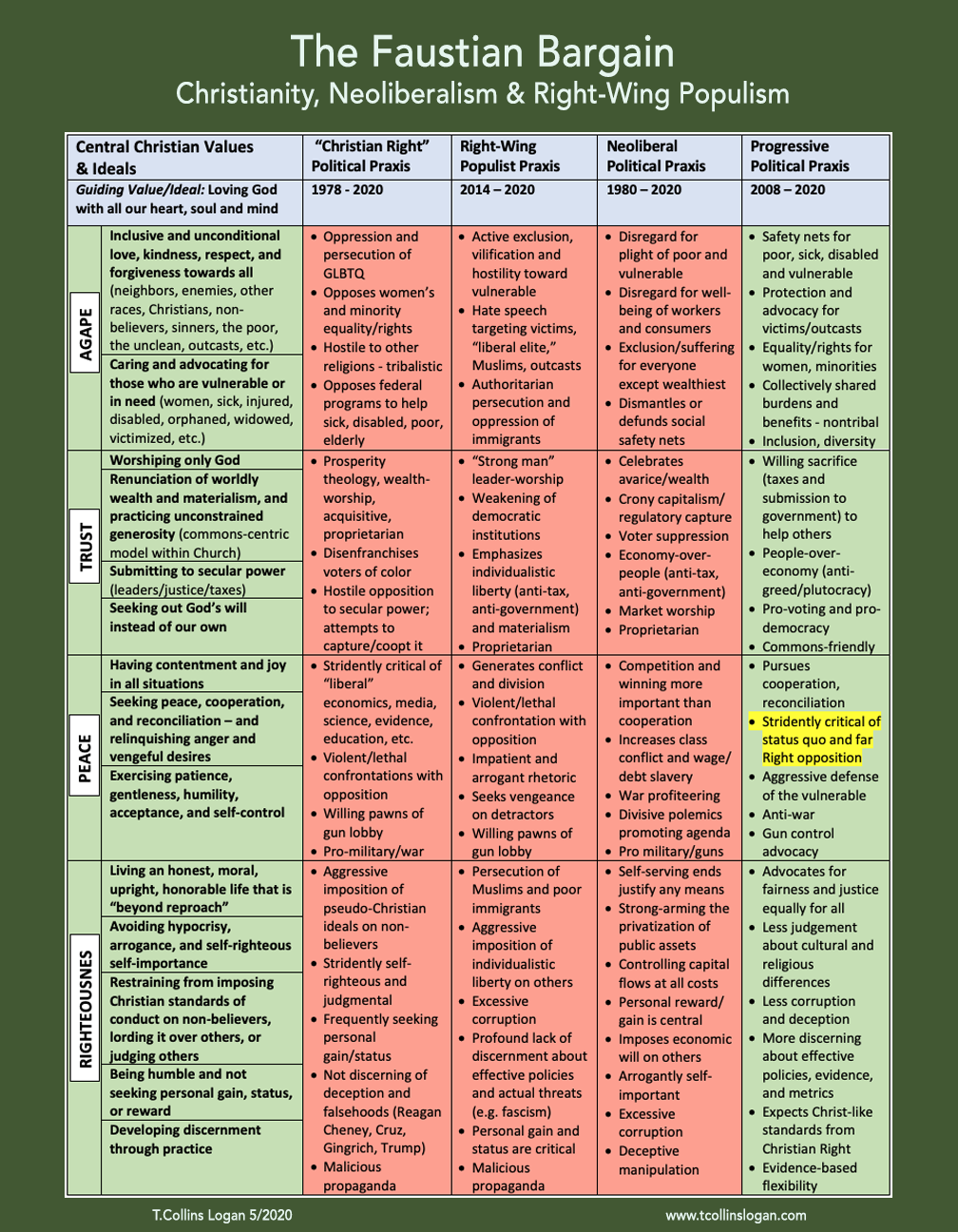

Here is an excerpt from my latest essay exploring the incompatibility between conservative Christianity and the New Testament's central Christian values and ideals.

"...my current thinking about this has distilled the primary dichotomy down to underlying contrasting views about

freedom and equality. This may be just one more oversimplification, but here are the basic propositions:

1. Progressives view freedom and equality as collective agreements, supported by evolving cultural norms and the rule of law, that facilitate the most comprehensive collective benefit possible for everyone in society. In other words, progressives view equality between all citizens, and the maximization of freedom for each individual, as a consequence of mutually agreed societal expectations. And why are those agreements important? Because they can achieve egalitarian outcomes across all of society. Importantly, the equality and freedom of all people are predetermined assumptions about both ideal individual rights and the ideal conditions in which they ought to live. Therefore, progressivism tends to view itself as inherently aspirational, aiming for “life as it could be,” in perpetual opposition to a flawed status quo.

2. Conservatives view freedom as a natural right of every person that facilitates their ability to pursue beneficial outcomes according to their skills, aptitudes, and capacity to compete with others. Equality is likewise viewed more through a lens of merit – it is less a predetermined assumption about all people being equal, and more a possibility of achieving equal standing in society that can be earned through demonstrated effort. And what is the presupposed outcome? That some people will be winners, with a greater experience of equality and freedom, and some people will be losers, with less of that experience –but the conservative accepts this as the natural and somewhat fixed order of things. Therefore, conservativism tends to view itself as inherently pragmatic, embracing the status quo of “how things are” – a static view of cultural norms that benefit those who achieve privilege and position – and defending ways those norms can predictably continue.

Much time and effort could be spent appreciating the subtleties of this topic – details like equality of outcome verses equality of opportunity, facilitation of agency verse extinguishment of agency, positive verses negative liberty, and so on – but it seems to me that this boils down to different approaches to

ending poverty, deprivation and oppression in their many forms. The conservative views the world as rich with opportunities, with the only major barriers to actualized freedom and equality – and the consequent attenuation of poverty, deprivation, and oppression – being interference or competition from other individuals, and interference or competition from civic institutions. The progressive, on the other hand, views the world as encumbered with many structural and pervasive cultural barriers (racism, sexism, classicism, ageism, tribalism, etc.) that need to be removed through collective agreements –most often embodied in civic institutions and the rule of law – in order for freedom and equality to be actualized, and for poverty, deprivation, and oppression to be vanquished. At its core, therefore, this remains a diametric opposition.

But which approach does the New Testament endorse? What does Jesus promote? For me this is where things get really interesting. Because the New Testament consistently presents very much the same contrast we see embodied in progressivism and conservativism. With regard to “the world as it is,” there are frequent reminders in scripture that the world cannot be changed, that its machinations, power structures, oppressions, arrogance, striving, and injustices must be accepted and its burdens dutifully borne. At the same time,

the kingdom of God is promoted as “the world as it should be,” full of compassion, forgiveness, kindness, humility, generosity, and mutual aid. Christians are encouraged again and again not to conform to the world’s values, priorities, and divisive norms, but instead to evidence the fruit of the spirit of Christ (

Gal 5:22) by reforming personal priorities and values – and the collective priorities and values within the Church – to reflect a new way of being. In fact, such reformation is itself proof of the kingdom of God’s establishment in the world. And what characterizes that new way of being? The virtues of

righteousness, peace, trust, and

agape that we explored in the earlier table (see below), and which are embodied in progressive praxis.

This contrast between the way of the world and the way of the spirit

is really the central drama of all New Testament scripture. As Jesus personifies the way of the spirit in all of his interactions and pronouncements, he is confronted with antagonism from the status quo – from those who wish to preserve the way of the world and their own places of power and privilege within it. Jesus and his Apostles become ambassadors of a more egalitarian ideal, an aspirational vision of “life as it could be” in the kingdom of God, and thereby encounter tremendous resistance and resentment from those who currently benefit from the status quo, and therefore feel threatened by anything that challenges its power structures. This is why the Pharisees and Sadducees were enraged by Jesus’ pronouncements, why the Romans were concerned by Jesus’ rise in popularity, and what ultimately resulted in Jesus being condemned to death by crucifixion. Jesus was the radical progressive visionary of his time, while the pragmatic and entrenched conservatives were, in fact, the ones responsible for his death."

You can read the full essay via this link.

You can read the full essay via this link.

Great question…but beware of propaganda.

Here are some of the many ways a capitalist view of “wealth” (as the accumulation of capital) is created, many of which have actually become much more common than “adding value with labor” in today’s highly financialized economy:

1) Buy cheap and sell high — without adding any value, but simply by timing the selling and buying the right way (this includes holding for a time, so that time does the work), or by exaggerating (persuading, cajoling, deceiving, “selling”) the value downward when purchasing, and then upward when selling.

2) Use leverage and debt — borrow against existing assets and invest(or lend out) at a higher rate of return than it costs to service the debt.

3) Lend money.

4) Charge rent for something that is already owned — this is income creation without adding value, and can occur over many generations after initial ownership (by a family or business) is established.

5) Gate-keeping — charging for access or the right to use anything, including someone else’s knowledge or innovation, some unimproved land, a road that was paid for by others, high speed Internet vs. low-speed (there is little difference between the two in provisioning — it’s merely a software setting), and so on.

Those are the biggies IMO. There are others that do require a little bit of labor for a disproportionately high return, and they are equally common today. These include creating artificial demand (direct consumer advertising by pharmaceuticals is a common locus for this), opportunistic market entry, privatization of publicly held resources, regulatory capture, etc. But any reasonable standard, these are all nefarious, unethical ways of creating wealth.

My 2 cents.

There are two great sadnesses for me:

1) Then end of the books themselves — the end of the story and the parting from wonderful characters I had grown to love.

2) The passing away of magic, the other races of Middle Earth, the reverence for Nature, and the consequential ascendence of Man. More than the moment of departure “into the West” of specific characters, this was the end of an age.

These are of course echoes of other personal and cultural endings. Of my own childhood, of a romantic and magic-filled view of the world, of an ability to lose myself entirely in a work of fiction, of Tolkien himself as an author, of the power of books in the lives and minds of young people, of the richness and importance of folklore in earlier cultures and times, of the common belief in elves and faeries, etc.

But the larger metanarrative here is that human beings — with their industries, machines, brutal conflicts, self-absorbed ignorance, and feet of clay worldliness — would now become the dominant power of Earth…and all of the richness, knowledge, beauty, and complexity of Tolkein’s races, cultures, languages, and myths would fade away forever. The finality of that loss still haunts me, some 40+ years after reading LOTR.

At the heart of this, I think the resonance so many readers have felt is with Tolkien’s celebration of a profound mystery and beauty grounded in Nature. The Ents. The tree-dwelling Silvan Elves. The eagle Gwaihir’s critical aid to Gandalf. The tranquility and harmony of the Shire itself. All of these and so much more evoke the real magic woven into these books: a deeply felt sense of wonder for a natural world that transcends human pettiness and anthropocentric priority, and asks us all to live within it, as the hobbits and elves did, rather than dominating or subjugating Nature. And of course there was the warning of the fate of the Dwarves, who delved to greedily and deeply into Nature’s treasures.

And that resonance is most deeply felt by those of us who have, for many decades, sounded the alarm about the careless exhaustion, destruction and toxic pollution of species, habitats, and ecosystems of Earth. For me, this is the most heartbreaking message Tolkien delivered with LOTR: that human ascension would signal the end of Nature’s primacy, thriving, and very existence. And, so far at least, Tolkien was heartbreakingly prescient.

My 2 cents.

Thanks for the question. There are many excellent ones. Here are a few I would recommend as starters, listed in the order I think would be helpful:

An Anarchist FAQ

Demanding the Impossible - Peter Marshall

An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice - William Godwin

The Ecology of Freedom - Murray Bookchin

The Conquest of Bread - Peter Kropotkin

David Graeber - Debt: The First 5,000 Years

What is Property - Pierre Proudhon

My 2 cents.

First of all: sigh.

Here are some of the reasons socialism is poorly understood — especially in the United States.

1) First, there is a lot of anti-socialist propaganda. The Red Scares after WWI and WWI, and then McCarthyism, generated some profound misinformation about socialism that has persisted to this day. Mainly, this propaganda was invented to protect wealthy owner-shareholders who were (and still are) terrified of losing control over the exploitative, extractive wealth creation that they benefit from. It’s why there is also anti-science propaganda, anti-education propaganda, anti-intellectualism propaganda, anti-expert propaganda, anti-government propaganda…it’s pretty endless. The idea is simple: maintain the status quo that funnels capital to the rich at the expense of everyone else. It’s a pretty strong motivation to dissuade people from looking at other ways to do things.

2) General ignorance about history and the positive models and impacts of socialism is another reason. There are many socialist countries that were never authoritarian communist like the U.S.S.R. or China. But folks don’t learn much about those in U.S. schools or from corporate controlled media. Some of those countries still exist. If an “anti-socialist” attempts to argue that socialism has never succeeded, I simply ask them to name some of the thriving examples of municipalism, anarcho-syndicalism, social democracy, and anarcho-communism that have existed and still exist, and explain why they think those countries are failures. But of course they never can, because all of the “anti-socialist” propagandists I have engaged (really without exception) are completely ignorant of those countries.

3) Ideological fervor and blindness. This is a pretty common problem among vocal anti-socialists who are deeply committed to capitalism. The discussion rarely centers around facts or evidence, and anti-socialist arguments quickly devolve into logical fallacies (straw man arguments, red herrings, false equivalence, confirmation bias, whataboutism, etc.). Just look at many of the posts in this thread, where the level of vitriolic frothing-at-the-mouth is fairly extreme. It’s hard to help such folks understand where they are mistaken. Generally, when I share corrective facts and narratives about socialism with “true believer” market fundamentalists (neoliberals, laissez-faire, Randian objectivists, Austrian School fans, Chicago School fans, etc.) the anti-socialists usually fall silent, dwindle into passive-aggressive sarcasm, or morph into sociopathic ranters.

4) Here there be trolls. Social media provides ideal hunting grounds for folks who just want to provoke and engage in rhetorical combat.

My 2 cents.

The sad reality right now (April 22, 2020) is that we just have be patient and wait. Careful, considered, critical reasoning won’t do much good without sufficient and accurate data — and that is really what we’re all lacking right now. Too many news, data, and information sources that are usually reliable have been propagating incomplete, inaccurate, lr even dangerous information from the very beginning of the pandemic. Many political leaders are of course even worse about conveying a nuanced and carefully considered understanding of COVID-19. And even medically savvy folks are struggling with what information they feel they can trust. As a consequence, a lot of people remain bewildered, afraid, and confused…and will likely have to remain in that state until we have more data. A lot more data. In perhaps two months’ time, we will hopefully have a much better picture of the COVID-19 pandemic, including how to manage it. For now…we must simply be prudent, and patient.

That said, I will offer a few resources that have been “better than average” IMO at conveying the evolving picture of COVID-19:

1) NBC Nightly News has done better than many other networks in the U.S. in providing carefully vetted, “cautiously accurate” information around COVID-19 in a very condensed format each night.

2)

Science | AAAS and

Science News Magazine are pretty reliable sources for ongoing developments, and delve into much greater depth.

3) STAT has been better than most at delivering accurate breaking scientific and medical news.

4) To get a very helpful picture of the global data on COVID-19,

Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) - Statistics and Research at Our World In Data seems to be a great resource.

5) And of course the

Coronavirus section of the W.H.O. website is…well…slightly better than mediocre, though sometimes slow to catch up on the latest developments.

And…well…that’s about it, unfortunately. I’ve been pretty appalled at the wild inaccuracy of many other news and information sources — including ones I have relied upon for many years. They are truly terrible right now.

Lastly, I’ll offer my own web page on COVID-19, which attempts to keep up-to-date on the latest information and provides resources for further research:

COVID-19 Overview | Integral Lifework

Of course…this answer must itself be taken with a grain of salt, as I’m just clawing my way through a twilight of understanding like everyone else.

I hope this was helpful.

So the OP is definitely onto something here. For one, direct and semi-direct democracies do exist where people continue to have a say in their own governance on nearly any issues they choose to engage on. Examples range from Switzerland (semi-direct) to Rojava and the Zapatistas (direct). And those systems work surprisingly well.

So why do we have representative democracies instead of direct or semi-direct democracies?

Well, the history of U.S. democracy provides a very good example of how this came about. Most of the Founding Fathers were, frankly, terrified of direct democracy, and echoes of those fears remain today when folks use terms like “mob rule” to characterize such a system. Instead, the Founders decided that the best way to moderate the “mob” of the electorate was to ensure only educated, wealthy, ostensibly white, landed gentry (men of course) could be appointed by states to the Senate, to act as a firewall against any overreach of the will of the people. Kinda funny, isn’t it? Not really democracy at all…

but that non-democratic system remained in place in the U.S. until the 17th Amendment, ratified in 1913. So for nearly the first century-and-a-half of U.S. “representative democracy” the voters couldn’t even elect their own representatives (senators in this case).

In short, the primary answer is fear that people wouldn’t be educated or world-wise enough to make good decisions. And we hear that same argument from many conservatives today.

So who gets to decide, then? As it was in the beginning, so it remains today in the U.S.: Because of issues like corporate lobbyists such as A.L.E.C, massive amounts of dark money funding election campaigns because of Citizens United, and imbalanced corporate control of media messaging after the Fairness Doctrine was ended by Ronald Reagan, those with financial means and social capital and status have ended up making a lot of the most important decisions about who gets elected and what legislation gets passed. This is why the U.S.A. has always been a mix of democracy and plutocracy — with the balance leaning more and more toward plutocracy in recent election cycles.

Again, there are many direct and semi-direct democracies around the world that demonstrate how an engaged, thoughtful, and well-informed electorate can make excellent governance decisions about their own lives — both locally and nationally.

For more on this topic, I recommend these links:

Direct democracy - Wikipedia

The way to modern direct democracy in Switzerland

Switzerland: Swiss Direct Democracy

It’s pretty simple: physical distancing isn’t enough to stop an explosive spread of coronavirus. In order to open the economy back up at all, we need to be able to contain, track and treat COVID-19 so that overall disruption and fatalities can be reduced. To do that will require:

1) Better, faster, more widely available testing of COVID-19 infection and antibodies.

2) Adequate supplies of effective masks for everyone who is out in public.

3) Financial support for folks who are at high risk and aren’t able to do their job.

4) A treatment that reduces lethality and permanent injury from infection.

5) And, ultimately, both a vaccine that works and broader herd immunity.

Right now, we have NONE of these things. So this is simply going to take time.

However, folks are also increasingly realizing that there is a larger issue in play:

that we may not really want to “go back” to what we had before, and instead have an opportunity to address some pretty nasty systemic problems. Here is a great article about this:

We Are Living in a Failed State

My 2 cents.

This is a false choice.

The impact on jobs and the economy is temporary, not permanent. Also the numbers used aren’t even close to correct. The question would be much more accurately stated: “Should tens of millions of people experience a temporary loss of income — for perhaps a few months — so that a few million people’s lives will be saved?”

That is a bit closer to the mark in terms of tradeoffs. As to whether that is “just” or not, I suppose it comes down to the morality you are operating on — whether temporary economic suffering somehow trumps careless and avoidable death in your worldview. In reality, the economic impact of COVID-19 is much worse because we have structured our society to funnel all the wealth to a few people, while leaving the majority of the working population in debt and without much savings or assets. So the bigger question really is:

“Is it just that tens of millions of millions of people are so vulnerable to COVID-19’s economic impacts, mainly because a few thousands have accumulated all the wealth in society?”

My 2 cents.

Yes it can — but if and only if an “alternative interpretation” of a dogmatic worldview can easily be generated or argued. Since most group ideologies are grounded in their broader culture, and most individual ideologies are shaped by life experiences and that person’s native proclivities, it is relatively easy to separate out what a specific ideology may actually teach from what some fanatic group or individual lunatic believes. If, however, an “alternative interpretation” isn’t easily available, that’s when things become problematic. For example, it is very difficult to find anything redeeming in most white supremacist writings — there is no rational “alternative interpretation” that makes them less racist, irrational, or toxic. At the other extreme, a person who reads the Quran isn’t likely to arrive at the conclusion that it encourages all nonbelievers to be killed — because that’s not what the Quran teaches. In other words, it’s quite easy to arrive at an “alternative interpretation” of the intent of the passages in the Quran that advocate self-defense. So in this case even when some Muslims are engaged in violent fanaticism, even a non-believer can rationally conclude that these fanatics are acting out of their own selfish reasons, or have been manipulated and deceived, rather than really being justified by the ideology (Islam) they claim to espouse.

My 2 cents.

They don’t need to be different. Friendly competition with the mutually agreed-upon goal of creating excellence and innovation is, in effect, “cooperation.” What has happened in some cultures — most notably here in the U.S. — is that “competition” takes on hostile, winner-take-all, zero-sum game characteristics. At the same time, “cooperation” is seen by these same hostile competitors as a weakness — an opportunity to exploit or gain advantage. To some degree, the profit motive combined with monopoly and expectations of scarcity (i.e. fear) tends to encourage this non-cooperative competitiveness. It seems to be a sort of malady of being culturally immature.

My 2 cents.

Thanks for the question. My take is that there are many different reasons why COVID-19 is still being politicized and a unified effort is so challenging here in the U.S. — some of the reasons are more obvious, some more subtle. Here are a few that come to mind:

1) The profound political polarization of the country perpetuates partisan polemics — about everything. Nothing, really, can escape this gravity well right now.

2) Lots of folks are benefitting from politicization of COVID-19 — politicians taking a political stance to help them stay in office, companies and media outlets rushing to fulfill the latest priorities of the current political agenda, and so on.

3) There is a paucity of trustworthy leadership, competence and appropriate knowledge at both the national and state levels of government. This is true for both the legislative and executive branches. And, without these qualities, all the really remains is rhetoric, persuasion, and “Us vs. Them” jockeying to move the policy needle in any direction. It’s a sad situation.

4) The American electorate has an unfortunate habit of “going with their gut” instead of really thinking things through carefully. This is a gross overgeneralization of course — there are plenty of thoughtful voters out there — but, on the whole, I think this has been a pervasive problem. And one of the consequences is that these people’s opinions are not usually shaped by facts or logic, but by emotional appeals, groupthink, and the magnetism of their chosen “authority” on a given subject. It is, essentially, the perfect environment for political propaganda and maneuvering to shape all public discourse and narratives around something like COVID-19.

5) Most politicians — especially those who have survived a pretty hostile environment and remained in office for years — reflexively act on political instinct first, and everything else second. It’s behavioral conditioning because of an antagonistic status quo.

My 2 cents.

This is a very difficult topic. I resisted conservatorship for my own mom when she began to show signs of dementia. I wanted to respect her independence and agency. Unfortunately, over the course of two years, she was victimized by numerous scams that depleted all of her supplemental income, and ran up a large amount of debt. She then began to have difficulty caring for herself physically. Initially, I took the route of adding some in-home support for her (she was still living in her own house at the time) — help with errands, nurse visits to monitor her medications and blood sugar, help with bathing, and so on. But those in-home resources began to report increasing concern about my mom’s behaviors and risk (leaving the stove on, leaving the front door open in winter, hostile outbursts, eating foods that made her conditions worse, poor personal hygiene, and so on). My mom did not seem to be “losing it,” she seemed okay to me. But I was in denial.

Then she had a stroke — one that was very likely caused by her poor compliance with diabetes treatment and diet.

After initial hospitalization and rehab, my mom returned home. Her stroke still wasn’t enough to convince me she couldn’t be independent, and she was still very high functioning. In discussing the situation with my mom she also made it clear the she wanted to “die at home” and didn’t want to move into assisted living or have more controls put on her life. She had always lived as a free spirit, and so this all made sense to me.

Then I discovered the scams, debt, and loss of resources — but only when my mom started to ask me for money. She had elaborate excuses about what had happened to her income, but eventually admitted that, in addition to clearing out all of her reverse mortgage, she was cashing her Social Security check each month and giving that to the scammers (in its entirety) as well. She didn’t see anything wrong with any of this, because….

She was told she had won two million dollars and a Mercedes, and that she needed to pay taxes on the prizes in order to receive her money and new car.

No matter how I tried to convince her that this was obviously a scam, she couldn’t be reasoned with. She was sure she had won a prize. She had even gone down to a local police station to show them the letter and complain about not receiving her winnings. And although the police then became aware of the fact she was being scammed, they could do nothing. When I spoke with them, they said “she is a willing party…unless she files a complaint herself, we can’t go after these scammers.” Apparently, this sort of scam on the elderly is reaching epidemic proportions in the U.S.A.

So, finally, the critical mass of red flags got through my denial, as my mom was now:

1. Not managing her chronic health conditions at all, and putting herself at risk.

2. Not managing her money at all, and not able to pay bills or buy food.

3. Not able to keep herself or her house clean.

4. Giving her money away — anytime she received any income (including from selling her beloved jewelry and collected art at a pawn shop!), she would call the scammers immediately to pay them. The scammers would then send a cab to pick up the money, sometimes even driving my mom to the bank or a Walmart to cash a check. It was insidious and constant. And if my mom wasn’t delivering, the scammers would call my mom ten or fifteen times each day to bully her into giving them more money.

So I called adult services (the “elder abuse” department) for the state and asked what I could do. The social worker there was amazing. She helped me jump through all of the hoops necessary to get my mom into conservatorship. Thankfully, my mom still trusted me enough that she agreed to one voluntarily. However, working with a local senior center in town, I was also able to have her assessed by a psychiatrist who confirmed the dementia diagnosis and evidence of incapacity to manage her financial affairs. This was a key step, and would have been even more necessary if my mom had not voluntarily entered conservatorship.

At first, I tried a third party conservator who lived in my mom’s town — I live on the other side of the U.S. so this seemed to make good sense. Unfortunately, the conservator, a former law enforcement officer, was almost as bad as the scammers and provided no services at all in exchange for high fees. This included not paying my mother’s bills, which sent everything into a deeper downward spiral.

Eventually, I had to become my mom’s conservator myself. This involved yet another trip to probate court and another authorization for me to become “conservator of person and estate” for my mom. Again, this was voluntary. It would have been much more difficult had my mom not allowed it voluntarily.

I then embarked on a year of daily management of my mom’s health and finances. If I had not become her conservator, she would have ended up on the street or worse…and I likely wouldn’t have found out until it was too late to help. Now she is in a dementia care facility and doing fairly well — and that transition, too, would likely not have happened had I not been involved in her care. As her dementia progressed, my mom’s confusion and aggressive behaviors were putting her at substantial risk. She needed 24/7 care.

But that didn’t mean I didn’t feel guilty about “putting her in a nursing home,” which was exactly what she said she didn’t want. I felt terrible, especially because in her first few weeks all she could do was beg to be taken home. You could say the final vindication for the decision to move her into care came when she had a serious cardiac event that required bypass surgery. Had she not been in care, she would have died two years ago. Right now, she is doing well, and I can visit her via video chat. She doesn’t know who I am anymore, but she always smiles and is delighted to see a face she at least knows is familiar and kind to her. Her old friends who all live nearby occasionally come to visit her, too, and that always brings her joy in-the-moment as well. And, a bit surprisingly, she loves the food at the facility and some of the activities there, like bowling.

So, via this not-easy-and-simple answer, I hope I have conveyed how difficult the conservatorship decision — and process — can be. There have been lots of other hiccups, too, such as making sure my mom’s financial resources continue to be managed so that her care can be paid for. There have been other medical crises. There have been psychiatric crises. There have been challenges dealing with Social Security, Medicare Part B insurance, and so on. It really never ends, and it is never easy. But my mom could not have navigated any of this herself.

I hope this was helpful.

My sanity is bound by hope

That after this entombed stillness

Of prescribed isolation

We will resurrect ourselves

Casting away the layered dressings

Of our self-wrought calamity

And breathe fresh morning air

Thoughtfully renewed

In the garden of Earth

What will this new life be?

What will define the yearning brightness

That penetrates our darkest hour?

What clarion lures us forth

From this uneasy sleep?

What, really, is the point

Of our return?

Is it a soaring stock market?

Feverish consuming of endless stuff?

A disregard for every living thing –

Even our own young?

Perpetual striving and toiling

To create another shiny lie

To summit in the dark?

Another hollow victory

Of affluent self-importance?

No…that is the chiseled rock

– An obsessive labor of futility –

That formed the cold and rigid damp

Of our own negation

That is the old way

Of unresurrected self

Blinded into foolishness

By a fixed and narcissistic gaze

To believe in the power

Of rebirth

Is to let go of childish things

And cleave to larger loves

A love of Others

In service and kindness

A love of Nature’s gifts

In respecting and protecting

A love of Beauty

In creating and enjoying

A love of Justice

In championing and obeying

A love of Sharing

In generosity and humility

And a love of Love itself

In remembering, and honoring, the Sacred

Without such reconsideration

We emerge from our tomb

Confused, rudderless, and distraught

Stumbling numbly

Backwards to Golgatha

Eager for the familiar comfort

Of being nailed up on a cross

Without grasping

This moment of renewal

We return to taunted suffering

Pierced by spears of debt

Where greed casts lots

For our lives and our possessions

Where all thirst is quenched

By vile distractions

And our soul cries out:

“Why have you abandoned me?”

This, now, is our chance

To ascend beyond the pettiness

Of “me” and “mine”

To roll away the stone

Of callous indifference

To shed the suffocating mask

Of fearful ignorance

This, now, is the Easter

Of humanity

The lush and fertile change

That delivers us

From ourselves

[Audio version:

https://soundcloud.com/user-701150728/covid-19-easter-2020v2]

Thanks for the question — I think it’s a very important one.

First some groundwork….

1. The opinion of many observers of human behavior is that insanity is a pervasive feature of the human condition. In fact, some would go so far to say that anyone presenting as perfectly normal should raise red flags, as they may be “faking it” in order to hide their genuine nature. I’m deliberately avoiding clinical language here, but the point is that, if we really dig around in people’s psyches, we will find evidence of all sorts of ideations and emotions that brush up against one or more particular disorders or dysfunctions. In fact this is likely just who we are as a species — perhaps such rich variation, including high intelligence, creativity, and psychiatric disorders, is a feature of consciousness itself.

2. The difference between someone who ends up receiving a specific DSM diagnosis, and someone deemed to be within a “normal” range, has mainly to do with three things: a) their level of functionality in routine daily life; b) their self-perception about their own level of function or level of distress; and c) a critical mass of formal and informal observations from others about their level of function or distress. A “high functioning, well-adjusted” person who is able to maintain relationships, avoid committing crimes, maintain a job, be satisfied and relatively at peace with their emotional experiences, not set off flares of concern in others who observe their behaviors, and so on will generally not be diagnosed unless and until some major crisis interferes with some or all of these metrics.

Okay, so keeping these fundamentals in mind, let’s now answer the question: ”Where is the line between being highly creative and intellectual, versus being schizotypal?”

There have actually been some hypotheses and research about correlations between intelligence, creativity, and mental illness. Here is a representative sample:

1. The rate of anxiety and mood disorders in Mensa members is over twice as high as in the general population, and they had a higher incidence of other psychiatric disorders as well. (

High intelligence: A risk factor for psychological and physiological overexcitabilities)

2. The rate of several psychiatric disorders in adolescents with

low fluid intelligence is higher than the general population. (

Fluid intelligence and psychiatric disorders in a population representative sample of US adolescents)

3. It may be that the only difference between creative genius and psychiatric disorders — and antisocial disorders in particular — is temperament (innate or acquired behavioral propensities), as both extremes exhibit many of the same capacities and deficits. (

The Association Between Major Mental Disorders and Geniuses)

From the literature available (and of course there is a lot more), it would appear that there is as yet no firm consensus about the relationship between creativity, intelligence, and psychiatric disorders. But there is a lot of data. What we might tentatively conclude from that data — in combination with our own felt experiences, insights, and observations — is that the “line” between creative genius, high intelligence, and psychiatric disorder is quite fuzzy. Disorders, and perhaps especially of the antisocial variety, can correlate with low flexible intelligence and creative problem-solving (fluid intelligence), or coincide with creative genius. It is, in effect, a broad expanse of gray area that is not well understood or easily navigated.

However, what remains to guide that navigation are the aforementioned metrics — qualities of function, equanimity, relationship, sociality, distress and so on. If those qualities achieve “acceptable” levels for the individual, the individual’s intimate relationships and community, and social norms…well then, there is little cause for concern. If those qualities fall short in any of these arenas — either consistently or because of an acute crisis — then it is probably time to consider reaching out for supportive help for the affected parties.

So it really comes down to accurately and honestly assessing those metrics. In my own integral lifework practice, I expand those metrics into thirteen dimensions of well-being, and find that a major disruption or deficit in any one dimension is really enough to cause imbalances and suffering in someone’s life — and an indication that they need to address the neglected dimension(s). Here is a self-assessment for those thirteen dimensions (you can ignore the bit about submitting the assessment to me for review, and just use it as a guideline for your own self-care):

https://www.integrallifework.com/resources/NourishmentAssessmentV2.pdf

As indicated in the “Nourishment Assessment,” I do highly recommend you include others in the assessment process.

I hope this was helpful.

Democracy has always been pretty fragile, but it has some natural enemies. I think we can easily observe four categories of those enemies to democracy:

1. Some enemies can be characterized as those persons or groups who do not wish to cede power or wealth — or those who wish to accumulate more power and wealth than others in society. We might call these

“active external antagonists.”

2. There are the inherent characteristics of the electorate, which are what we might call the

“passive internal barriers,” such as apathy, ignorance, low intelligence, immaturity, or gullibility.

3. There are then

“passive external barriers” such as the lack of adequate or reliable information to make complex voting decisions, or logistic or institutional difficulties in voting or registering to vote.

4. And finally there is

“active internal sabotage,” where voters remain willfully ignorant on issues that require their vote, actively shun voting as a consequence of conspiracy beliefs, adopt an ideology that opposes democratic institutions and practices, or consciously abdicate their own agency through misplaced faith in an individual or political party (and just vote in lockstep conformance with that party).

So the “first step to losing democracy” can really be any of these enemies gaining a sufficient foothold in society to undermine its democratic institutions. More alarmingly, there might be combinations of these enemies occurring at the same time. As a worst-case-scenario, we would see ALL of these enemies converge on democracy in the same period of time. Unfortunately, that appears to be the condition of many democracies around the globe right now.

As an example, I can speak to what is occurring in the U.S. in this regard. Here is how those enemies have been rearing their ugly heads over the past few election cycles:

1.

Active external antagonists: On the one hand, we have special interests with enormous wealth who have captured election campaigns, lobbying efforts, and consequently control legislation and regulatory agencies. This group can broadly be characterized as “neoliberal crony capitalists.” On the other hand, we have the “active measures” from Russia and other state actors who seek to confuse, disrupt and distort democracy in the U.S.

2.

Passive internal barriers: This has been a pervasive downward spiral in the U.S. for many decades — apathy, ignorance, low IQ, immaturity, and gullibility have been hallmarks of the American electorate across all parties and affiliations. This may be cultural, it may be a consequence of Americans “relaxing” into relative affluence and comfort, it may be the result of a passive consumer mindset that is conditioned to be “sold” on every idea or decision, or all of these things.

3.

Passive external barriers: Although logistic and institutional difficulties have increasingly been engineered by the GOP (through voter disenfranchisement, reduced voting locations and times, barriers to voter registration, gerrymandering, and other strategies, etc.), there is also the issue of real and exponential complexity in voting decisions. Also, although there is good, reliable information available for voters, it is increasingly challenging to differentiate it from the much louder noise and distraction of propaganda media outlets.

4.

Active internal sabotage: Certain ideologies and beliefs have taken root in the U.S. that amplify pessimism, disinterest, and even despair and hostility regarding voting and democracy. These can be found across the entire political spectrum, but seem to be concentrated (and much more aggressive) in the far Left and far Right. Sometimes, the aim of these ideologies is to dismantle democracy and democratic governments entirely. Somewhat ironically, a common theme among these disaffected voters is that they would like to have “more freedom” than the current system affords them, but of course by not participating in or undermining democracy, they are self-oppressing:

reducing their own agency and freedom to pre-democracy levels.

So we aren’t in a great place right now. To restore democracy — which after all is the greatest collective expression of human freedom that has ever arisen in the world — we all likely need to a) re-engage in democracy as actively and thoughtfully as possible, and b) forcefully oppose and reform the internal and external “enemies” to democracy described above. If we can do this, I think there is hope. But we may genuinely be running out of time….

Some additional references:

Neoliberalism

Disinformation (includes links to more reliable information sources)

The Goldilocks Zone of Integral Liberty: A Proposed Method of Differentiating Verifiable Free Will from Countervailing Illusions of Freedom (essay)

Unfortunately, at this point we have to.

This wasn’t always the case. At one time, you could live in a small community that was insulated from other communities, from the rest of the country, and from the rest of the world.

That really isn’t true anymore. A single national election can determine (and has determined) the following — as have the critical mass of our daily purchasing decisions, the media we consume and support, where we decide to live and pay taxes, how we raise our children, and so on:

1. Whether or not the women in your community can get an abortion.

2. Whether or not you and your family will have healthcare.

3. Whether or not your community has more than one employer — or any at all — due to trade policies (voting in elections) and consumption habits (voting with your dollars).

4. Whether or not you can own a gun, carry a gun, the type of gun, etc.

5. Whether or not a local business can pollute the air or water nearby, or be held accountable for the illness and death that pollution causes over time.

6. Whether or not the BLM land or National Forest near your town becomes primarily an industrial center for raw materials extraction, or primarily a recreational area now and for future generations, or some balance of both.

7. Whether or not you and your children receive a decent education — or any college education at all.

8. Whether or not mass media can fabricate news or be required to provide balanced viewpoints (i.e. the Fairness Doctrine…gone now)

9. Whether or not you can buy something made anywhere but China.

10. Whether or not countless species of animals go extinct each year.

11. Whether or not future generations have anything left of the Earth to enjoy or thrive in (i.e. responding to climate crisis, avoiding nuclear war, etc.).

12. Whether or not someone who lives next door or very far away — even in another country — has a say in any of these matters in their own lives.

I could go on…but I’m sure you see the point. Because of the massive complexity and interdependencies of our current economic and legal systems, it is almost impossible to remain isolated and pretend that how we act (and vote, and consume) individually or locally doesn’t have a cascading impact on everyone else — both in our immediate community and all around the world, and both now and in the future. This is a de facto condition of modernity…to ignore it is just to remain willfully ignorant.

Therefore, everything really is political, now more than ever, and the question becomes: Will I pretend to be an atom who can act any way I please, engaging in life as merely a series of impersonal transactions, without acknowledging the impact of my choices on everyone and everything else, and fantasize that I have no responsibility to consider that impact? Or will I accept the impacts and influence of my choices on others and the world around me, the persisting and expanding relationships between my life and everyone and everything else’s, take responsibility for those relationships, and live more carefully and caringly…?

My 2 cents.

Thanks for the question.

First, that’s already happening. Established movements/practices like P2P and Open Source, for example, as well as the democratization of knowledge and creative sharing via the Internet, and efforts to return economies to a commons-centric model. The “trigger” has simply been the desire to create and collaborate, while sidestepping an obsession with ownership and profit, often with very specific and pragmatic ends (in the real world). So in both the digital realm, and the material realm, “spontaneously collaborating and sharing without coercion” is a

fait accompli.

In terms of expanding just these two approaches, efforts are underway. Check out the

P2P Foundation,

Creative Commons,

http://commonstransition.org and of course

Wikipedia.

In terms of “how we get there,” well, certainly educating ourselves (and helping educate others) about the current models is an important part of the mix — and, perhaps more than that, creating a positive vision around them. At the same time, encouraging folks to question the destructive aspects of capitalism is also important — to help them recognize that we do, in fact, need to change our systems and philosophy of production and distribution in order to survive as a species.

There are also forms of activism that can help “trigger” a change. I cover some of those here:

L e v e l - 7 Action. There is a lot to take in on that web page, but the essential idea is a multi-pronged approach to change that addresses many different levels and arenas of engagements. Please consider spending some time there and following the links to more in-depth discussions of many topics.

In a very real sense, the current COVID-19 pandemic may help folks reevaluate the inherent flaws of our global economic system, and perhaps consider some of these alternatives.

I hope this was helpful.

The roots of progressive ideals can easily be traced to the Enlightenment in Europe, where increased understanding and knowledge through reason and scientific inquiry were intended to bring about improved conditions for everyone in society. This was in contrast to the established “traditions” of that time, and so the idea of progress for the betterment of humanity became associated with the Enlightenment itself. And since two core tenets championed by Enlightenment thinkers were liberty and equality, the process of social reform (and revolution) to upend the old traditions and social order also became associated with the Enlightenment.

Now the initial inspiration for the progressive movement in the U.S. was a response to the rise of industrial capitalism, along with its abuses of workers and concentrations of wealth in a small elite, initially during the Gilded Age. In a way, the power of large corporations became a stand-in for the social hierarchies and abuses of old that the Enlightenment sought to address: capitalism replaced feudalism but mirrored the same oppressive power structures as the wealthy owner-shareholders took the place of aristocracy. In this sense progressivism echoed socialism’s response to the same challenges — and with many of the same proposals (worker solidarity, civil rights, etc.). But it is really only at that thirty-thousand-foot level that we can draw parallels between those two movements — or track their evolution over time — but we can see inclinations of the Enlightenment reflected in both. Progressives were primarily interested in returning “power to the people,” and having representatives of local and federal government be much more responsive to the electorate than to special interests like the wealthy elite. Initially progressives focused primarily on empowering and protecting white, working poor folks and their families in this way — and included women’s suffrage in that mix. While socialism of that time also shared this focus, only some socialists advocated advocated as vehemently for strengthening democracy overall.

Today, although it not as coordinated or clearly defined a movement, the central tenets that continue to guide progressives is strengthening civil rights and civil society in opposition to plutocratic oppressions, and continuing to champion liberty and equality. So we can say that these have remained the “traditional values” of progressivism since its beginnings.

Interestingly, what has also persisted in progressive ideas and strategies since the beginning is an almost ridiculous (in terms of effectiveness) diversity of approaches. There has never really been uniform agreement among progressives about how to solve the wealth concentration problem, worker empowerment problem, or improving our elected representation problem. Which is why someone might indeed ask the question of whether “traditional progressivism” has really ever existed. So we can say that the intentions — the goals and aspirations — of progressives have always been the same, and unifying in that respect. But methods…no, that’s always been a hodgepodge of tactics and proposals. In fact, sometimes these have been contradictory approaches — for example, some have emphasized centralized federal government solutions, while others emphasized more localized or distributed solutions (via community organizations, NGOs, etc.); some have emphasized collective solidarity (in unions, civil rights movements, etc.) while others have seemed more individualistic (individual freedom of choice, abortion rights, etc.). These differences probably owe themselves to different conceptions of both liberty and equality.

Lastly, there are some reliable commonalities between most, if not all, modern progressives. The original emphasis on liberty and equality is still present, but it has expanded considerably since the Enlightenment. Today these values are championed not just for white working poor, their families, and women’s suffrage, but also for expanding the same rights and protections to people of color, to animals and the environment, to the sick and elderly, to the LGBTQ community, and so on. And the approaches to championing these interests still rely on reason and scientific inquiry to a substantive degree. The ultimate aim? To improve conditions for everyone — this is still how progress is defined — in opposition to those who would prefer to retain the old hierarchies and concentrations of wealth and power. Fighting plutocratic oppression with democracy and strong civil society is really still the heart and soul of progressivism, and what makes it a longstanding “tradition” in almost every respect.

My 2 cents.

Interesting question. I experience those as two sides of the same coin…or two aspects of the same process. Depth is necessary to navigate complexity, weigh everything carefully and multidimensionally, allow lots of space for multiple vectors of cognition and insight — in order to arrive at the “aha.” Clarity is necessary to distill, to filter the muddy waters of cognition, to differentiate the signal from the noise, to discern and understand the “aha” when it presents itself. Both are forms of discipline that, in combination, can synthesize discernment and wisdom.

My 2 cents.

First I would encourage everyone

not to listen to anything Trump says…ever. Any sensible person with an average IQ can observe that Trump can’t stop lying and contradicting himself. At every turn, he has downplayed the severity of COVID-19 and its impacts. Trump is, by almost any measure, an incompetent idiot. So instead, we should all become a bit more educated about the details of the novel coronavirus ourselves. Here is a page with helpful links and a frequently-updated overview:

COVID-19 Overview

As to the impact on those under a “stay-at-home” order….

The potential negative impacts are both economic and psychological. Some people (like me, to be honest) are natural hermits who are perfectly happy spending time alone, and can keep themselves occupied and entertained without a lot of social interaction. Others are wired to be much more social, engaged, and entertained through interactions and activities that involve many people. This latter group will undoubtedly suffer a great deal during this period of social distancing — in particular I’m thinking of young people whose entire self-concept and self-esteem may be grounded in their social interactions. So having online activities and ways to connect virtually may be very important, and it seems as though there is already recognition of this and attempts to increase such online activity options. Nevertheless, depression and anxiety may be real battles for large numbers of highly social people right now. To address that challenge, I recommend folks take a look at the thirteen dimensions of nourishment (there is a free overview and self-assessment on the

Integral Lifework website), and see if they can add some activities that nourish parts of themselves they may be neglected.

On the economic side of things, the situation could get very dire for those who have lost all of their income. There are several efforts at the state and federal levels to help people — from direct monetary payouts, to temporary debt and recurring bills forgiveness, to free medical care for COVID-19 tests and treatment. The benefits of these efforts will become clearer in the coming weeks, and they will certainly help cushion the blow. But they will only be effective for the short-term. The more permanent solution will be a) a COVID-19 vaccine, which is likely 12–18 months away; or b) a more successful and reliable COVID-19 treatment than anything tried so far — which could arrive much more quickly than a vaccine. Once either or both of these are in place, then economic recovery can begin in earnest. At the same time, this may also be a helpful moment in human history to reevaluate whether neoliberal crony capitalism — with all of its inherent resource depletion, worker exploitation, negative externalities (like climate change), and economic inequalities — should remain our primary global political economy. It just might be time for a change that would help us be better prepared for future crises like COVID-19. To that end, here is a link to an alternative political economy that is more equitable, sane and sustainable:

L e v e l - 7 Overview.

My 2 cents.

Thanks for the question.

There are a few factors in play I think. First, there is a fair amount of research that shows differences in right-leaning an left-leaning people — both in terms of the values (or “virtues”) that are most important to them, and in the emotions with which they most frequently operate and are motivated. I’ll leave it to you to figure out which is which from the lists below. Of course, there are also folks who are closer to the middle, sharing characteristics of both groups. But in times of crisis, polarization tends to be even greater, so for now we’ll just look at the two extremes….

Characteristics of Group A:

1. More closed-minded and reactive to things that are new or “different”

2. Strong fear-based reasoning, often centered around losing status (both personally and for their group)

3. High tolerance of cognitive dissonance (when facts don’t match beliefs) and rejection of evidence that contradicts their beliefs — sometimes to the point of rather stubborn stupidity

4. Strong sense of loyalty to own tribe and traditions, resulting in reflexive “Us vs. Them” reasoning

5. Highly skeptical of science, government institutions, genuine altruism, collective concerns, leveling the economic playing field for everyone, and the importance of civil society itself

6. Insists that private enterprise is “more efficient” than government in providing public goods (healthcare, utilities, etc.)

Characteristics of Group B:

1. More open-minded and accepting of things that are new or “different”

2. Strong inclusive and compassion-centered reasoning, sometimes to the detriment of their own status and the status of their group

3. Low tolerance for cognitive dissonance, and fairly frequent updating of position based on new evidence

4. Hardly any loyalty to own tribe and traditions, and so sometimes creating “circular firing squads” within leadership

5. Strongly motivated to embrace science and justify positions and policies with scientific evidence; more trusting of government institutions; confident that altruism is real and important; and generally more invested in collective concerns, leveling the economic playing field for everyone, and the importance of civil society itself

6. Is skeptical of the profit motive’s efficacy in navigating or providing public goods

Now inject a new crisis into the situation: a previously unknown and highly contagious virus that requires close coordination between all governmental institutions; demands reliance on scientific data to plan an effective response; is indifferent to status and partisanship (i.e. doesn’t favor one group over another); and reveals profound weaknesses in privatization of public goods, where the profit motive simply doesn’t work for the scale of response required.

I think when we break down the political spectrum to these kinds of characteristics, it quickly becomes evident why left-leaning folks tend to respond one way, while right-leaning folks tend to respond in an opposite fashion.

My 2 cents.

The right-wing propaganda machine has finally lost some of its momentum and, as embodied in the idiocy of Trump, is being abandoned as a farce. The echoes of that propaganda still persist in the fear-mongering around a Sanders nomination — from media on the Left and the Right — but folks are beginning to see through the supposed “moderate” critique to what it really is:

the decades-long disinformation campaign of right-wing think tanks, ideological politics, and thought leaders that strives to reject all socialist ideas. This started all the way back with the Red Scare of WWI, was amplified by the neoliberalism of Hayek, Mises and Friedman, came to a head in the era of McCarthyism, resurged in the 1970s after the panicked

Lewis Powell Memo (a reaction to the populist revolts of the 1960s), resurged again in the “trickle down” economics of Thatcher and Reagan, was championed even more when the Tea Party movement was coopted by crony capitalists like the Koch brothers, and has now come to a ludicrous climax in the election of an impulsive, megalomaniacal fool as POTUS.

To understand why this conservative “anti-socialist” movement has persisted for so long, just follow the money. The U.S. has had a mixed economy — with elements of both socialism and capitalism — for over a century, but wealthy owner-shareholders always want more. And that means they strive for weaker government and “less interference” from pesky regulations, human rights, environmental protections, etc. This has always been about the rich wanting to get richer, and the only answer to Adam Smith’s “vile maxim” (i.e.

“all for ourselves, and nothing for other people”) has been the stronger, more democratic civil society championed by socialism (see

How Socialist Contributions to Civil Society Saved Capitalism From Itself). To appreciate just how hard neoliberal conservatives have fought to control and consolidate wealth, I recommend perusing this web page, and then following some of its links:

L7 Neoliberalism

Along the same lines, folks are beginning to realize that democratic socialism (as exemplified by much of Northern Europe) is NOT the same thing as authoritarian communism (i.e. Soviet-Style communism) — despite the ongoing right-wing propaganda to the contrary. (For more on this see

http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/democratic-socialist-countries/)

In essence…young folks are becoming better educated about what democratic socialism really is.

However…stay tuned for the right-wing propaganda machine to begin spouting lies about how socialism “always fails,” etc.

My 2 cents.

What a delightfully inane question. Thank you for the opportunity to entertain.

Some questions that we might ponder to burrow down to the heart of this matter, run along these lines:

What have you contributed to society that makes you believe you have the right to expect your neighbors to be obligated to pay for…

1. Firefighters to save you from a burning building while you sleep?

2. Roads for you to drive to work on?

3. A standing army to defend your community from foreign invaders?

4. Police officers to answer a 911 call when someone breaks into your home, threatens your family, or mugs you in the street?

5. Government funded research into vaccines for deadly diseases that would otherwise never be developed?

6. Emergency disaster assistance when a tornado, flood or fire wipes out your entire town?

7. Medical facilities to treat you if you are “out of network,” don’t have adequate insurance coverage, and don’t have enough money to pay out-of-pocket?

And so on…

There are so many things we take for granted as a “right,” when really they are the privileges that societal organization affords us

because we have all agreed to cooperate in that society and abide by its rules. In reality, we are all just entitled “freeloaders” when we expect civil society to function at all on our behalf. After all, what have we, personally, done to contribute to the structures, agreements, benefits, protections, and rights of that society? What have we, individually, done to build up or maintain any of privileges society grants us? Usually absolutely nothing…except pay taxes, and conform to the rule of law, both of which many people only do grudgingly.

Really, there are just a few central questions that we need to answer for ourselves:

1.

Which civic institutions do we wish to prioritize as the most important, and which members of society do we want to primarily benefit from them? (These are really two sides of the same coin IMO)

2.

In whom do we wish to vest the power to make decisions about the prioritization of civic institutions and who benefits from them? In other words, do we want a democratic process, an autocratic process, an oligarchic process….?

3.

How do we wish to pay for these civic institutions, manage them, and maintain them?