(Special thanks to Petyr Cirino, whose thoughtful exchanges with me inspired this particular essay.)

(Special thanks to Petyr Cirino, whose thoughtful exchanges with me inspired this particular essay.)

As daily events around the world illustrate, we have unquestionably arrived at the age of human superagency — in terms of both positive and negative impacts. On smaller scales of individuals and groups, there are the negative impacts of mass shootings, suicide bombers, toxic waste leaks, chemical plant explosions, contamination of water supplies with heavy metals, contamination of local food chains with pathogens or harmful chemicals, and other disruptions of limited scope. And of course the positive side of this local superagency includes the complex interdependent systems and services that support burgeoning municipalities and allow them to thrive. So in both constructive and destructive ways, we can easily see how complexity, technology and superagency are linked. On the national and global scale, a more collective superagency manifests on the one hand as disruption of everything from infrastructure and commerce to news and elections by a small group of dedicated hackers or activists, to the accelerating extinction of well-established species all around the planet as a consequence of human activities, to the radioactive contamination of vast swathes of air and water after a nuclear power plant meltdown, to the extreme temperatures and chaotic weather patterns resulting from over a century of human industry. On the positive side, humanity has been able to extract and distribute limited resources far and wide on a global scale, linked and negotiated disparate cultures and language around the planet to the benefit of many, and generated and shared huge amounts of knowledge and information to an impressive degree. At these larger scales, complexity and technology are also intimately entangled with superagency, but such impacts seem to depend more on the collective habits and influence of huge populations than on individuals or groups. Ultimately, it seems to have been the aggregate of individual, group and global population impacts that constitute a tipping point for the blossoming of human superagency on planet Earth.

But why does this matter?

One conventional answer is that this matters because our superagency has far outpaced our moral maturity; that is, our ability to manage superagency at any level — individually, tribally or globally — in a consistently beneficial or even sane fashion. Of course this is not a new observation: social critics, philosophers, prophets and artists throughout history have often observed that humanity is not very gifted at managing our own creative, acquisitive or political prowess; from the myths of Icarus and Midas, to the admonitions of Aristotle and Solomon, to tales of Frankenstein and Godzilla, the cautionary narratives of precipitous greed, clever invention and unabashed hubris have remained virtually unbroken across the span of human civilization. But should this perennial caution be our primary concern? Don't civil society, advancing education, widespread democracy and rigorous science mitigate the misuse or overreach of personal and collective power? Don't such institutions in fact provide a bulwark against an immature or degraded morality's ability to misuse humanity's greatest innovations and accomplishments? Aren't these the very failsafes intended to insulate society from its most irrational and destructive impulses...?

First, I would attempt to answer such questions by observing that moral maturity — along with all the societal institutions created to maintain and protect it — has been aggressively undermined by capitalist enterprise to an astonishing degree: via the infantilization and isolation of consumers, the substitution of internal creative and interpersonal riches with external commodities, the glorification of both greed and material accumulation, and the careful engineering of our addiction to comfort. But these concerns are the focus of much of my other writing (see

The Case Against Capitalism), not to mention the more deft and compelling writings of countless others, so I won't dwell on them here. Instead, I would turn some attention to what is perhaps an even more pernicious tendency in human affairs, one that has persisted for just as long as all these other degrading impulses and influences. Yes, in a globally collective sense, our moral maturity and capacity for positive moral creativity has seemingly regressed or stagnated even as our superagency has increased — and yes, capitalism is largely to blame for the most recent downward spirals. But there is something more basic and instrumental in our psyche that energizes greed, hubris, arrogance and reckless destruction...something fundamental to our being that needs to be called out. Something that, by any measure, reliably contributes to all sorts of evildoing.

And of course attempts to explain the nature of evil are also not new. Many have attempted to ferret out the source of our darkest impulses, accrediting them to supernatural beings — Aite, Eris, Angra Mainyu, Satan, demons and mazzikim, bhoot and Pishacha, etc.— or describing it in terms of psychological phenomena like selfish compulsions and egotism, death drives (

Todestriebe), maladaptive behaviors, severe mental disorders, and so forth. But identifying a more accurate underlying causal pattern will, I think, require a departure from these traditional frameworks. Instead, perhaps we can evaluate a series of straightforward cognitive errors that supportively interconnect, amplify and then calcify over time to create a specific, deleterious and measurable impact on both human interiority and society. Perhaps "evil" can, on some basic level, be defined as a simple cognitive mistake, and "good" as the correction of that mental error.

A Corrosive Troika Defined

With respect to causality, there appear to be three consistent factors that continually surface across the vast terrain of human affairs:

1.

Misattribution of causation (as an unintentional mistake or conditioned response)

2. Intentional

masking of causation (as deliberate and targeted distortions that reinforce misattribution); and

3. Willful

forcing of causation (designed to support and reinforce deliberate distortions)

Together these create a

virtual causality — that is, causality that is almost completely disconnected or substantially insulated from reality, while still imitating certain believable elements of the real world amid elaborate rationalizations. It is this pretend causality that entices a willing suspension of disbelief — for those who are vulnerable, coerced, deceived or conformist — that perpetuates self-insulation and additional supportive distortions. So let's take a careful look at each of these components, in order to appreciate just how instrumental they are in everything human beings think, feel and do, and how the modern age is shaping them.

I. Misattribution

Humans make this cognitive mistake so often it seems almost ridiculous to point it out: we blame the wrong culprit for our problems, and consequently pursue the wrong solutions to fix them. Add some additional, deleterious unintended consequences to these kinds of mistakes, and the resulting conditions could easily be described as "what leads to much suffering in the world;" that is, what has perpetuated much of the destruction, unhappiness, suffering, pain and annihilation throughout human history. The dangers of misattributed causation are identified in many if not most wisdom traditions — we can discern this in admonitions about judging others to quickly, gossiping about our suspicions, bearing false witness, words spoken in anger, living by the sword, throwing the first stone, revenge, showy public worship, etc., along with repeated encouragement to forgive without conditions, be patient and longsuffering, generous and caring, humble and trusting. Such concerns are certainly echoed in more recent empirical and rationalist approaches to both knowledge and socially constructive behaviors as well; for example, research in psychology around the misattribution of arousal to incorrect stimuli, or the application of the scientific method in understanding and resolving complex empirical challenges. But sometimes the obvious and longstanding begs restating, so we'll briefly address it here.

Let's consider a few relatively neutral examples, then drill down to a few more compelling, nuanced and disturbing details. For example, most reasonably perceptive adults might agree from their own direct observations, fairly straightforward and simplistic reasoning, or trusted sources of learning that:

1. Sunlight warms the Earth.

2. Submerging crusty pots and pans in water for a time makes them easier to clean.

3. Regularly and violently beating a domesticated animal will eventually induce behavioral problems in that animal.

4. A sedentary lifestyle, devoid of exercise and full of rich foods, will lead to chronic health problems.

5. Smiling at people with genuine openness and affection generally encourages openness and a positive emotional response in return.

6. A heavy object dropped from the second floor of a building onto someone's head is likely to kill them.

7. Really awful things happen to perfectly decent, undeserving people with some regularity.

8. Choosing "the easy way out" of a given situation — that is, a choice that seeks to fortify personal comfort or avoids personal accountability — is often much less fruitful or constructive in the long run than making a harder, more uncomfortable choice that embraces personal responsibility.

There are probably hundreds of thousands — if not millions — of such causal chains that most people have internalized and rely upon to navigate their day-to-day lives. We may not always be consistent in our reasoning and application of them, and there are often exceptions or special conditions that moderate the efficacy of our causal predictions, but on-the-whole we usually learn over time which causal attributions are correct, and which are mistaken. That is...unless something interrupts that learning process.

And this is where I feel the discussion becomes interesting. For it is my contention that many characteristics of modern society not only disrupt our ability to learn and predict accurate causal relationships,

but actually encourage distortions and misattributions. How? Here again we will see how complexity, technology, and superagency strongly facilitate the disconnect...but also that we can add isolation and specialization to the mix as well. If, over the course childhood, my entire reference set for understanding causal relationships is defined by television and video games, and I have never thoroughly tested any of the assumptions inculcated through those media, how will I ever escape their fictional depictions? At around age eight or nine, I myself attempted to duplicate some of the crazy stunts Bugs Bunny and Roadrunner performed in Warner Brothers cartoons. I quickly learned that gravity, momentum, inertia, the velocity of falling objects, and host of other principles of physics were grossly misrepresented in those TV shows. I also learned that I did not recover from serious injury nearly as quickly as Wily Coyote did. But what if I hadn't learned any of this through experience? What I had always been insulated from real-world testing and consequences? What if I kept assuming that the fiction I was being shown for entertainment was the actual truth...?

I find this a handy metaphor for modern society, because, throughout most early stages of development, human beings can now remain completely insulated from experiences that shape our understanding of

actual causality. Over the years I have witnessed young people trying to ride a horse, play an instrument, write a story, draw a picture, shoot a gun, drive a car, run a race, play a sport, build a tree house, use martial arts...and a host of other activities or skills...simply by imitating what they saw in a movie, played in a video game, or read in a book. And of course that doesn't work — because they do not understand the subtleties of the causal relationships involved. This is what competently learning a skill most often represents: appreciating all of the causal relationships that influence a given outcome, and practicing each one in turn until they are mastered individually and conjointly. What application of force, in which direction, using which tool at which angle and with what kind of finesse, results in unscrewing a rusty bolt on an old bicycle? Knowing the answers to all the steps in a causal chain, especially through personal experience, is what most reliably produces predictive efficacy over time. But if I've never actually ridden a horse, or hiked a mountain, or slaughtered a chicken, or grown food in a garden, or learned to shoot a bow and arrow, or installed a fence, or built a house, or felled a tree, or any number of other activities that might have been the common experience of folks a mere generation or two ago, how can I presume to know how the world around me really works, or how to accomplish the simplest tasks without the aid of technology, advanced tools or specialized workers on which most of the developed world has now come to rely?

Well I can't, and no amount of assistance from my iPad, smartphone or virtual assistant is going to help me develop a felt, somatic-intuitive understanding of basic causal principles — let alone more complex causal chains. I will remain blissfully ignorant of how things work. However, these same technologies also provide an ever-advancing level of virtual pseudoagency — by turning home appliances on or off, monitoring a child's activities, video conferencing with coworkers, ordering groceries to be delivered, recording a threatening phone call, troubleshooting a vehicle's error codes, managing finances, donating to a charity or political campaign, signing a petition, etc. — so that I begin to believe that I really have no need to grasp those causal principles. In fact, the increasing scope of that virtual pseudoagency begins to feel a lot like superagency itself, even though the only causal relationship I am required to maintain is the one with my iPad, smartphone or virtual assistant. Here again, complexity, technology, superagency, isolation and specialization conspire to support my entanglement with virtual causality. And if I confine myself to the same routines, the same environments, the same social groups and virtual communities, the same homogenous culture and mass media...it is possible for me to remain disconnected and insulated from authentic causality for my entire life. So, just hold that thought if you will.....

Let's now examine a second set of causal relationships that are a bit more abstracted from direct experience, rely on more complex reasoning, or encourage us to develop greater trust in authoritative sources of information:

1. Human industry has been accelerating the warming of the planet to levels that will likely destabilize human civilization, and eventually endanger all other life on Earth.

2. Travelling through space at velocities approaching the speed of light slows down time for the traveller relative to the space being travelled through.

3. Gun ownership may make people feel safer, but as a statistical reality it places them at much higher risk of being shot themselves.

4. One of the best ways to mitigate the most pernicious negative impacts of drug addiction on individuals and society is to legalize, tax and regulate drugs, and then allow them to be administered in a controlled environment with medical oversight, and by folks who are also trained in providing treatment and resources to anyone who is willing and able to overcome their addiction.

5. Quantum entanglement (what Einstein called "spooky action at a distance") indicates an immediate relationship between particles over vast distances, potentially negating the speed of light as a limiting factor of data transmission.

6. Educating people from an early age about safe sex, family planning and child rearing, and allowing them easy, affordable access to reproductive healthcare and choices, is one of the most effective ways to reduce unwanted pregnancies, teen pregnancies and abortions.

7. Corporate monopolies can often be much more inefficient, coercive, exploitative and corrosive to civil society and individual well-being than the bureaucratic or cumbersome institutions of democratically elected governments.

8. Educating and empowering women to become more economically self-sufficient, and more intellectually and emotionally self-directed, is likely the single most effective means of raising a culture out of poverty, slowing overpopulation, and strengthening local civil society over a short period of time.

Now you will notice that this second set of causal relationships has some notable differences from the first set. Each statement has required more words for an accurate description, for example, and a deeper and broader contextualization. The causality being described can also be much larger in scope, and causal chains much more subtle, abstract or tenuous. And even as these relationships are increasingly distanced from direct experience and observation, they also tend to involve more complexity and interdependency, making them that much more difficult to grasp. Still, any reasonable person who has carefully and thoroughly educated themselves about each of these issues will eventually acquire a justifiable level of confidence in the stated conclusions,

because, with sufficient attention, diligence and effort, the causal relationships actually become just as obvious as the ones in the first set.

But wait....let's return to the problem of lacking experiential (felt, somatic-intuitive) understanding about the real world. As very few people will have the chance to experience any of the causal relationships in the second set in a subjective, firsthand way, an additional challenge is created: we will then often be forced to rely on the few people who have the specialized knowledge, expertise and experience to educate us about these causal relationships. And we will need to be able to trust their judgment — and often their exclusive agency — at least to some degree, even though we may not fully comprehend what they are describing in a fully multidimensional way. And, as we shall see, this whole enterprise is subject to a host of additional influences and caveats, so that we may once again find ourselves relying on our iPad, smartphone or virtual agent to support our understanding. Once again our technology, isolation, specialization, superagency and complexity conspire to add more distance and effort to clear or accurate causal comprehensions. Now consider the accelerating complexity of every gadget, tool and system upon which we rely to navigate the complexity of our world to levels beyond our basic knowledge, and the distance increases further still. And as we anticipate the imminent expansion of virtual reality technology itself into more and more areas of our lives, we can begin to imagine just how disconnected human beings will inevitably become — from each other, from themselves, and from the causal workings of the world.

With this is mind, for many people there is also a pronounced gap of doubt between these two sets of causal relationships, with the second set seeming much more tentative, conditional or questionable. For these skeptics, it often will not matter how much evidence is presented in support of any given conclusion...especially if that conclusion contradicts their values system, or challenges certain fundamental assumptions they hold about the world, or is perceived to undermine their preferred information authorities, or pokes and prods at their sense of identity or place in society. Given the choice, the skeptic may instead opt for tolerating higher and higher levels of cognitive dissonance. Of course, the highest level of understanding about these topics may again just be armchair expertise, with no real-world experience to back it up. In such cases, it might seem easy to attribute what are essentially irrational or ill-informed doubts about complex but verifiable attributions of causation to ignorance alone — or to cognitive bias, the Dunning-Kruger effect, tribal groupthink, being intimidated by complexity, ideological brainwashing and manipulation, abject stupidity, or some other equally dismissive explanation. In fact I have made this judgmental error myself, often amid roiling frustration that someone really seems to believe that, to paraphrase Asimov, their ignorance is "just as good as" rigorous investigation and knowledge.

But this has been, I now suspect, a glaringly lazy oversimplification; itself yet another misattribution of causation. Instead, what I now believe is actually happening is something much more intricate, and much more intriguing.

II. Masking

There are plentiful reasons why an individual or group might be strongly motivated to persuade themselves or coerce others into believing that one thing is responsible for certain outcomes, when it is really something else entirely. Consider such real-world conditions as:

1. I want to sell you something that you don't really want or need, and in order to part you from your money, I fabricate causal relationships to facilitate that end. For example, claiming that if you purchase a certain supplement, you won't need to exercise or change your diet to lose weight. Or that if you make a given long-term investment, you will be able to retire from your job decades earlier than you would otherwise. Or that if you trust in the products, services or advice I am selling you, you will achieve happiness, romance, social status, or a desirable level of financial success. And so on. This is perhaps the most pervasive example of intentional causal masking and deliberate deception — except of course when the salesperson (or friend, or coworker, or public official, etc.) may actually believe that the causal relationship is real, in which case they were just hoodwinked into complicity.

2. I am confused, fearful, insecure and frustrated by an increasingly complex and incomprehensible world — a world in which my identity is uncertain, my role in society is uncertain, my existential purpose has come into question, and I am simply unable to navigate the complexity around me with any self-assurance that I have any real agency or efficacy. I am also feeling increasingly lonely, isolated and disenfranchised by fast-paced, constantly changing urbanization and leapfrogging technologies, in combination with the pressure-cooker-effect of burgeoning population density. I feel I am in desperate competition — for both resources and achieving any personal value to society — with everything and everyone around me...and I feel that I am losing that race. So I latch onto a group, belief or ideology that helps relieve the panic, and inherent to that process is my masking away the actual causes of my existential pain and suffering, and investing in much simpler (but inaccurate) causal relationships through which I can imagine that I have more influence or control. And thus I may join a religious group, or political party, or online community, and actively surrender my own critical reasoning capacity in favor of comforting groupthink or ingroup/outgroup self-justifications.

3. Some impactful life experience or insight has inspired a reframing of all of my consequent observations and experiences according to a new paradigm — a paradigm that radically departs from previous assumptions, and applies a new filter for causation across all interactions and explanations. For example, after surviving a brutally violent event, I feel the need to protect myself and everyone I care about with elaborate and oppressive safety rules, rigid communication protocols, expensive security technology, and a host of lethal weapons. After my experiences, I simply view all interactions and situations as potentially dangerous and requiring a high degree of vigilance and suspicion. In my revised worldview, everything and everyone has become a potential threat,

and I must always be prepared for the worst possible outcome. In this way I have masked all causal relationships with potential calamity and catastrophe — and actively persuade others to do the same. In this sense, I have become conditioned to partial reinforcement — similarly to a gambler who wins intermittently, or a mouse who receives a chunk of cheese at arbitrary intervals for pushing on a button in his cage; whether that partial reinforcement invoked positive or negative consequences, I will insist on maintaining masked causation in order to prop up my compulsions.

4. I have made an error in judgment tied to investment of emotions or efforts, which was then followed by other errors required to support that initial error in judgment, until a long series of decisions and continued investment has created its own momentum and gravitational mass, and now seems an inescapable trajectory for my life and my identity. Perhaps I became invested in some logical fallacy or bias (confirmation bias, appeal to authority or tradition, slippery slope fallacy, vacuous truths, courtesy bias, hot-hand fallacy, etc. — see more at

Wikipedia), or initially overestimated my own knowledge or competence in some area, or trusted the advice of some cherished mentor, or took on some tremendous risk or commitment I didn't fully understand, or simply fell into a counterproductive habit that initially seemed acceptable...but has led me down an ever-darkening road. Whatever the case, I now find myself rationalizing each new decision in support of a long chain of mistaken judgments, and must of necessity consciously or unconsciously mask all causal relationships to protect my own ego or self-concept.

Regardless of the impetus, once this masking process begins, it can rapidly become self-perpetuating, a runaway train of misinformation and propaganda that eventually acquires institutional structures like rigidity, bureaucratic legalism, self-protective fervor, a dearth of self-awareness, and so on. In fact, potent beliefs and indeed entire ideologies have sprung forth from such synthesis, to then be aggressively propagated by adherents, with all provable causes forcefully rejected in favor of fabrications that conform to the new, hurriedly institutionalized worldview.

Recalling the two sets of causal relationships mentioned previously, our modern context of isolation, complexity, technology, specialization and superagency certainly seems to lend itself to both the masking process and its runaway propagation and institutionalization. It has become much easier, in other words, to mask the second set of seemingly more abstracted and complex causal relationships — or to invoke vast clouds of hazy interdependencies in either set —so that causation can be craftily shaped into an occluded, subjective miasma of "alternative facts." And although deities, fate, synchronicity, mischievous spirits and superstitious agency may still be credited with many bewildering events, there is now an industrial strength, global communications network that can instantly shape and amplify false explanations for a wide array of phenomena. Via social media, troll farms, sensational journalism, conspiracy theorists, pedantic talk-show hosts and the like, we have a well-established, widely trusted platform to breed outrageous distortions of the truth. And we can easily discern — from the consistency of the distortions over time, and by whom and what they vilify — that the primary aim of nearly all such efforts is to

mask the actual causes of countless economic, social, political and moral problems, and redirect the attentions and ire of loyal audiences to oversimplified explanations, straw man arguments, and xenophobic scapegoats. It is professional-grade masking at its finest.

That said, in the age of instant information access and pervasive mass media aggregation and dissemination, I would contend it has now become critical for these propaganda engines to excel beyond spinning evidence or cherry-picking supportive data, and to begin

engineering events that align with a given narrative in order to secure enduring conformance. In other words, to reach past merely masking causation into the realm of actually reshaping it. This is what the deliberate,

willful forcing of causation seeks to accomplish, and why extraordinary amounts of effort and resources — at least equivalent to those being expended on causal masking itself — have been spent in its pursuit.

III. Forcing

Willful forcing in this context is primarily about the intentional, frequently sustained manufacturing of causal evidence. For example, lets say I am seething with jealousy over a coworker's accomplishments, and I am filled with a petty lust to sabotage them. At first, I might attempt to mask the cause of their success with malicious gossip: what they did wasn't all that great, or they must have cheated along the way, or the boss was favoring them with special help, or the coworker must have been performing favors for others to achieve such results. But if

masking the actual cause of their success (that is, their credible competence, talent, hard work, etc.) isn't having sufficient effect, and I am still raging with vindictive spite, well then perhaps arranging some fake proof of my coworker's faults or failures will do the trick. Perhaps leaking a confidential memo from human resources about accusations of sexual misconduct? Or feeding them subtly incorrect data on their next project? Or maybe promising them cooperation and assistance in private, then denying it in public when it sabotages their efforts? If I keep at this long enough, I just might induce some real failures and shatter the "illusion" of my coworkers success. This is what willful forcing looks like, and is sort of connivance we might expect from TV dramas. But nobody really does this in the real world...right?

Unfortunately, it happens all the time — and increasingly on larger and larger scales as facilitated by the global reach of technology, capitalism, media and culture. We've seen such tactics used in the take-downs of political leaders, in the character assassinations of journalists and celebrities, in carefully orchestrated attacks on government and corporate whistleblowers, in how various activist movements are dismissively characterized in mass media, and in the billions spent to turn public opinion against beneficial public policies and legislation that might undermine established wielders of power. But is any of this "forcing" creating a causal relationship that wasn't already there...? Well, as one example, if reports of what happened during the 2016 U.S. Presidential election are accurate, then forcing did occur, via DNC efforts that deliberately undermined Bernie Sanders in favor of Hillary Clinton; Republican state legislatures that deliberately suppressed Democratic voters with voter ID laws, restricted polling times and places, and other such tactics; and Russian hackers that aimed to alienate Blue Dog Democrats and independent voters away from voting for Hillary Clinton. Assertions that any individual or party who appeared to be leading in the polls actually did not have enough votes to win was...well...

carefully engineered to be true. This is what causal forcing looks like on a larger scale.

In a more sustained forcing effort over a longer period, the Affordable Care Act has also become a particularly potent example. In this case, there was a pronounced lack of initial cooperation from conservative state legislatures, relentless and well-funded anti-Obamacare propaganda to maintain negative sentiments across the electorate, and dozens of efforts in the U.S. House and Senate to repeal the ACA itself — all of which has now been followed by the even more deliberate defunding and insurance market destabilizing efforts from the Trump administration via executive action (eliminating ACA cost-sharing subsidies, etc.). And all of this contributed to

fulfilling the causal masking that was broadcast from those opposed to government oversight of U.S. healthcare — during the ACA's creation and passage, and every day since then. In other words, years of carefully planned and executed sabotage have been

forcing the invented causality of claims like "Obamacare is a total failure and will collapse on its own" to become true.

It isn't always necessary to force causal relationships, of course, to maintain lockstep conformance. There are plentiful examples in politics of people continuing to vote for a candidate or party who never fulfills any campaign promises...ever. But we must remember that masking — and all individual and collective investment in masking — only requires partial reinforcement from observations and experience, an ongoing emotional investment, a blindness to our own hypocrisy or groupthink, and a conditioned receptivity to deceptive salesmanship. So as long as there is occasional proof that some authority we trust got something right, or some attitude we hold is justifiable, or the ideology we have chosen will still offer us acceptance and community, or the rabbit hole we've ventured down with an endless chain of bad choices has few or delayed palpable consequences...well, then those who wish to influence the masses only need to effectively force causation in the rare now-and-again.

Still, I would contend that a consistent pattern of fabrication has been emerging over many decades now: first misattribution, then masking, then forcing, all eventually leading to calamity and ruin in human relations and civil society — and disruption of our relationships with everything around us — thereby generating a closed loop of virtual causality. But in case these assertions seem contrived, let's take a closer look at additional real-world examples.

Virtual Causality in Action

Initially, I considered using "trifecta" to describe this particular trio of causal entanglements, because the motivations behind it appear to be all about winning; that is, it is employed primarily to shape a status quo that either directly benefits those who crave more power, influence or social and material capital, or directly injures or oppresses anyone interfering with that desired status quo. Thus the troika often becomes the trophy, the prize-in-itself, as its inventions and propagation become emblematic of such self-serving success — in other words, a trifecta. But really, this need not be the specific intent behind causal distortions; in fact I would say that the virtual causality troika is unwaveringly damaging in human affairs,

regardless of its intent. Let's examine some evidence for this....

If out of fear, discomfort, confusion, ignorance or social conformance I begin to misattribute homosexuality to a personal choice — rather than the innate, genetic structures and proclivities, which are almost certainly the reality for most gay people — and then link that assertion to tribal groupthink and an appeal to my favorite authorities, an almost effortless next step is intentionally or reflexively masking the actual causality with my own preferred beliefs. That mask may be projected into many shapes: perhaps an unhealthy or perverse interest was encouraged in a person's youth that led them to "choose" being gay; or perhaps they were sexually abused by a parent, older sibling or family friend; or maybe there are emotional, social or cognitive impairments that have led them to fear the opposite sex; and so on. There can be quite elaborate masking narratives if the need for self-justifying beliefs is strong enough. From there, perhaps because the misattribution itself is so heartbreakingly mistaken, there is a corresponding urge to force the desired, invented causation. Which leads me to author studies that "prove" early sexualization of children and/or permissive parenting somehow encourages sexual deviance, promiscuity or gender instability; or to engineer "gay deprogramming" efforts that "prove" gay people can become straight; or creating dogmatic propaganda that authentic marriage can only be between "a man and a woman," that gay parents can never be allowed to adopt children because it is "unnatural," that gay people can't hold jobs where they could potentially "corrupt" children, and other such constructions that

create an environment where gay people are in some way prevented from becoming successful and happy in their relationships, families, and jobs — and indeed their overall integration in society — thus adding to my "proof" that being gay is not natural, healthy or wise. And this is how misattribution easily leads to masking, which then begs the reinforcement of

forcing.

So in such a potent and seemingly enduring real-world example, the deleterious effects seem closely tied to fearful and dismissive intent. But what about the other end of the spectrum? Consider the beliefs of many people in modern culture regarding the desirability of wealth, and in particular the necessity of commercialistic capitalism to create a thriving and happy lifestyle for everyone. Much of the time, this isn't a nefarious or malevolent intent — folks may actually believe that everyone aggressively competing with each other for more and more wealth is "a good thing," and, further, that such pursuits are morally neutral; in other words, permissive of an "anything goes" mentality with regard to wealth creation. And if I truly embrace this belief, I will tend to mask my own observations about the world, about history and economics, about social movements, about government and everything else in accordance with that belief. In my unconsciously reflexive confirmation bias, I will only recognize arguments and evidence that seem to support my beliefs. That is, I will mask the actual causality behind events and data that embody my preferred causality, assiduously avoiding empirical research that debunks the travesty of "trickle down" economics, or that proves most conceptions of the Laffer curve to be laughable.

Then, because my beliefs are not really supported by careful analysis of available evidence — and are in fact thoroughly contradicted by a preponderance of data — I will eventually go beyond seeking out research, media and authorities that amplify my preferred causation, and begin to force that causation in my own life, the lives of those I can personally influence, and via my political leanings and spending habits. On a collective scale, I will vote to have judges appointed who favor corporations in their rulings, or for legislators who create tax breaks for the wealthy, or for Presidents who promise to remove regulatory barriers to corporate profits. On a personal level, I will explode my own debt burden in order to appear more affluent, and constantly and conspicuously consume to prop up growth-dependent markets. And, on a global level, I will advocate neoliberal policies that exploit cheap labor and resources in developing countries, and the ruination of my planet and all its species of plant and animal, in service to the very few who are exponentially increasing their personal fortunes. In these ways, I can help generate short-term surges of narrowly distributed prosperity that do indeed reward those who have already amassed significant wealth, and who will vociferously confirm that everyone else in society is benefitting as well...even when they are not.

In this second example, there can be a truly optimistic and benevolent intent in play — a person may really believe their misattribution, masking and forcing will have a positive impact. But the results of the disconnect between actual causality and invented causation still wreaks the same havoc on the world. For in this case we know that it is not wealth alone — operating in some sort of market fundamentalist vacuum — that lifts people out of poverty or liberates them from oppressive conditions. It is civil society, education, democracy, accessible healthcare, equal rights protected by the rule of law, the grateful and diligent civic engagement by responsible citizens, and much more; this cultural context is absolutely necessary to enable freedoms and foster enjoyment of the fruits of our labor. Without a substantive and enduring matrix of these complex and interdependent factors, history has shown without exception that wealth production alone results in callous and brutal enslavement of everyone and everything to its own ends, so that to whatever extent we fuel our greed, we fuel destruction of our society and well-being to the same degree.

Here again we can recognize that isolation, complexity, technology, specialization and superagency tend to obscure causality even as they amplify our ability to mask or force causal relationships. So on the one hand, it is more difficult to tease out cause-and-effect in complex, technologically dependent economic systems, but, once certain key effectors are identified, human superagency then makes it much easier to manipulate temporary outcomes or perceptions of longer-term outcomes. And this is precisely why the troika we've identified can maintain the appearance of victory within many dominant mediaspheres, noospheres and Zeitgeists — at local, national and global levels. To appreciate these dynamics is to have the veil between

what is real and

what is being sold as reality completely removed — in this and many other instances. Otherwise, if we cannot remove that veil, we will remain trapped in a

spectacle of delusion that perpetuates the greatest suffering for the greatest number for the greatest duration.

As to how pervasive and corrosive virtual causality has become in various arenas of life, that is probably a broader discussion that requires more thorough development. But, more briefly, we can easily observe a growing body of evidence that has widely taken hold in one important arena. Consider the following example and its consequences:

Perceived Problem: Social change is happening too quickly, destabilizing traditional roles and identities across all of society, and specifically challenging assumptions about the "rightful, superior position" of men over women, white people over people of color, adults over children, humans over Nature, and wealthy people over the poor.

Actual Causes: Liberalization of culture, education, automation, economic mobility and democratization have led to wealthy white men losing their status, position and power in society, so that they feel increasingly vulnerable, insecure and threatened. And while their feelings of entitlement regarding the power they are losing have no morally justifiable basis — other than the arbitrary, serendipitous or engineered advantages of past traditions, institutions and experiences — these wealthy white men have become indignant, enraged and desperate. So, rather than accepting a very reasonable equalization of their status and sharing their power with others, they are aggressively striving to reconstitute a perceived former glory.

Misattributions: Recreational use of illicit drugs, sexual promiscuity, homosexuality, lack of parental discipline, immorally indulgent entertainment media, immigrants or races with different values, governmental interference with personal liberty and moral standards, and liberal academic indoctrination have all contributed to the erosion of traditional family values and cohesion, resulting in an unnatural and destructive inversion of power dynamics in society and the easily grasped consequences of interpersonal and group conflict, increases in violent behaviors and crime, and general societal instability.

Causal Masking: Establishing think tanks and funding research that supports these causal misattributions with cherry-picked data; using mass media with a dedicated sympathetic bias to trumpet one-sided propaganda about these same causal misattributions; invoking religious sentiments and language that similarly cherry-pick scriptural and institutional support for sympathetic groupthink and activism; generating cohesive political platforms and well-funded campaigns grounded in these misattributions — and in the dissatisfaction, resentment and anger they evoke; and, via populist rhetoric, generally emboldening prejudice and hate against groups that threaten white male power.

Causal Forcing: The strident dismantling of public education and access to higher education; cancelling or defunding successful government programs; capturing or neutering regulatory agencies; destroying social safety nets; rejecting scientific and statistical consensus in all planning and policy considerations; and engineering economic, social and political environments that favor the resurgence of wealthy white male privilege and influence. In other words, removing any conditions that encourage equitable resource distribution, sharing of social capital, and access to economic opportunity, and restoring as many exclusive advantages as possible for wealthy white men.

Consequences: A renewal of income inequality, race and gender prejudices, lack of economic mobility, and cultural and systemic scapegoating of non-white "outsiders;" pervasive increase in societal instability and potential for both violent crime and institutional violence; mutually antagonistic identity politics and class conflict that amplifies polarization and power differentials; coercive use of force by the State to control the increasing instability; and gradual but inevitable exacerbation of injustice and systemic oppression. Adding superagency, isolation, specialization, complexity and technology to this mixture just amplifies the instability and extremism, increasing the felt impacts of ever-multiplying fascistic constraints and controls. Ultimately all of this results in increasing poverty and strife, and in pervasive deprivations of liberty for all but a select few.

Countering Virtual Causality with a Greater Good

In response to the dilemmas created by the troika we've discussed so far, I 've been aiming to work through some possible solutions for several years now. I began with a personal realization that I had to address deficits in my own well-being, deficits created by years of conforming to toxic cultural expectations about my own masculinity, and the equally destructive path of individualistic economic materialism which I had thoughtlessly followed throughout much of my life. I encountered an initial door to healing through studying various mystical traditions and forms of meditation, which resulted in my books

The Vital Mystic and

Essential Mysticism. However, I also realized that this dimension was only part of the mix; there were at least a dozen other dimensions of my being that required equal attention and nurturing. As I explored these facets of well-being, I arrived at the

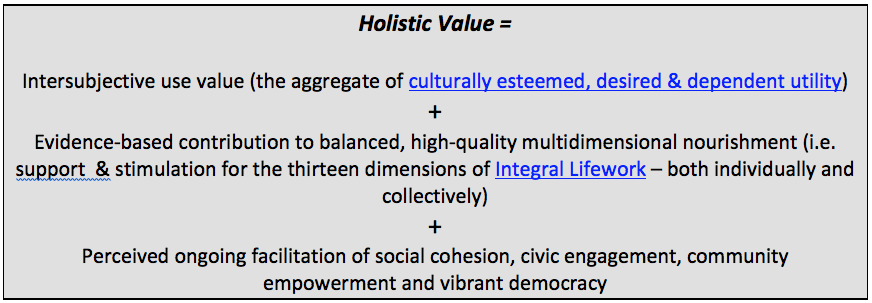

Integral Lifework system of transformative practice, my books

True Love and

Being Well, essays exploring compassionate multidimensional nourishment (see the essays page on this website), and the onset of an Integral Lifework coaching practice.

But something was still missing — something more causally fundamental that was hinted at in my previous experiences — and that is when I expanded my attentions to larger cultural, political and economic concerns. I began writing about the failures of capitalism, the distortions of religion and spirituality in commercialistic societies, the need for more holistic appreciations of liberty and knowledge, and the imperative of constructive moral creativity — offering a handful of what I believed to be fruitful approaches in these areas. Much of this culminated in the book

Political Economy and the Unitive Principle, and then in my

Level 7.org website, which explore some initial ways out of the mess we have created. Throughout these efforts, I presented what I believed to be some of the central causal factors involved in our current systemic antagonisms and failures, and some proposed next steps to actualize and sustain positive change. Of course what I have outlined in my work is

just one way to frame all of these situations and factors, and, regardless of intentions, there will likely be many details and variables yet to be worked through. This is why piloting different participatory, distributed and egalitarian options will be so important in the coming decade. The main point, however, is that, just as so many others have recognized, humanity cannot continue along its present course.

So this essay regarding virtual causality is an extension of this same avenue of considerations and concerns by burrowing through more layers of the onion — just one more piece of the puzzle, one more way to evaluate the current predicament...and perhaps begin navigating our way out of it. It seems to me that recognizing the cognitive distortions behind causal misattribution, masking and forcing are a central consideration for any remedy in the short and long term. These are the specific drivers underlying much of the evil in the world, perpetuating false promises that will only lead us over the cliff of our own demise. And in order to operationalize more constructive, prosocial, compassion-centered values, relationships and institutions on any scale — that is, to counter the corrosive troika and promote the greatest good, for the greatest number, for the greatest duration — we must address those cognitive distortions head on. We must end the reign of lies, and reinstate a more honest, open and well-reasoned relationship with causality. We must resist the false reality we are being sold, and open our eyes, hearts, spirits and minds to what really is.

How do we do this? Well, my own life's work describes one avenue, through which I advocate specific individual and collective efforts to reverse our downward spiral. But as I cruise around the Internet from day to day, I encounter countless and varied ideas, practices and resources supportive of positive change. Really, the answers are already out there (and within ourselves), just waiting for us to embrace them. All we really need to do to begin this journey is let go of the causal misattributions, masking and forcing that intrinsically fuel our perpetual fear, mistrust, anger and groupthink, and turn instead toward what is verifiably true — as complex, nuanced, ambiguous and counterintuitive as that truth may be. And there are already meaningful efforts along these lines within some disciplines —

Freakonomics comes to mind, as do websites like politifact.com, factcheck.org, opensecrets.org, and snopes.com — that model ways to peek through the veil of our mistaken assumptions and beliefs.

We just require more of these, across all disciplines and all media, along with open accessibility and the encouragement to seek them out. How hard could this be...? Even the most concerted efforts to deceive, distract and medicate us into conformance with virtual causality will fail, if we stop consuming them.

Lastly there are a handful of feasible personal practices that will help resolve part of this challenge. I discuss them in more detail in my writings on Integral Lifework, but essentially they include reconnecting with aspects of ourselves and our environment that modern life often encourages us to neglect. For example: spending alone time in nature; creating a disciplined habit of meditative introspection; investing regular time and energy in a supportive community that shares our values; shifting how we consciously process our experiences, from fast-paced analytical decision-making, to slower body-centered felt experience, to even slower heart-grounded intelligence; making sure we have space and time in our day for creative self-expression; and additional personal patterns that unplug us from electronic dependencies, naturally attenuate modern compulsions and addictions, and encourage both holistic self-care and compassionate engagement with others. Such practices are a powerful means of revitalizing the innate resilience, intelligence and creativity that millions of years of evolution have gifted our species. By returning to our authentic selves, we can regain an inner compass to help navigate these complicated and often alienating times.

When I was a technical consultant, there was a term for carelessly hurtling forward to keep pace with current technology, implementing the latest trends as soon as they emerged: we called it "riding the bleeding edge." The allusion was deliberate, because new tech could be risky, could fail, and might lack both support and future development. Instead, in my consulting I advocated a different approach: extending legacy systems and future-proofing them, or adding new technology that would integrate with legacy systems (or run in parallel with minimal cost) that offered extensibility for future technology integration — a bridge if you will. There was nothing particularly flashy about what I was doing, but this approach solved some fairly complex challenges, lowered hidden costs (such as retraining staff on new systems, or hiring expertise to support new technologies), and leveraged institutional knowledge and existing technical competencies. In my view, we need to do something similar for modern society, slowing down wide-scale deployment of "bleeding edge" innovation, and revisiting basic legacy components of human interaction and well-being. We need to create a bridge to our future selves that leaves as few people behind as possible, while preparing us for new ways of being and doing.

But our very first step must be to abandon virtual causality altogether, and reconnect with the real world in whatever ways we can.

-------------------------------------

Following up on some feedback I received after initially posting this essay....

Petyr Cirino pointed out that a powerful influence in modern society is our immersion in the 24-hour news cycle, which often results in a strong identification with the same. To be connected at-the-hip with nearly every noteworthy or sensational event around the globe, within minutes or hours of its occurrence, has come to dominate our sense of the world around us, what demands our emotional investment and prioritization from moment-to-moment, and is a determining factor in how we interact with people we know and familiar threads of thinking, how we view the people or thinking we don't know or understand, and how we feel about our lives and ourselves. The deluge of information and "newsworthy" events also tends to distract us from more immediate causality, contributing to an ever-expanding insulation from the real world and the abstraction of our interpersonal connections. Along with other mass media, the 24-hour news cycle consequently helps fuel, shape and sustain the causal troika to an astonishing degree. So it follows that divorcing ourselves from that cycle would be a helpful cofactor in first slowing, then remedying the perpetuation of misattribution, masking and forcing — for ourselves, and in how we amplify the troika in our relationships, social interactions, thinking and learning.

Ray Harris observed that limited cognitive capacity — along with a need to protect that capacity from too much information — may also play a role in evoking and energizing the causal troika. I think this is undoubtedly true, and would include it as a feature or consequence of complexity. Specifically, I think there is a snowball effect where complexity drives specialization, specialization generates insular language and relationships, and insular language and relationships contributes to isolation via homogenous communities and thought fields. These specialized islands barely comprehend each other, let alone regularly dialogue with each other, and cognitive capacity certainly plays a role in this phenomenon. I would also include other aspects of mind that contribute to troika formation, and which are also entangled with complexity, specialization and isolation. For example: how gullible someone is, how disciplined they are in their critical reasoning, how educated they are in general, how tribal their thinking becomes, etc. Addressing these tendencies may also become part of a long-term remedy, but of course there are genetic, dietary, cultural and relational factors involved here as well. It seems that any attempts to manage the troika tendency, or compensate for it in media and communication, would therefore require consideration of a sizable matrix of interdependent factors. Or maybe a majority of humans just need to become smarter, better educated, and learn how to think carefully and critically...? Certainly, we can encourage this through ongoing cultural liberalization — we just need to attenuate the influences of capitalism in order for that liberalization to take its fullest course.